“I think one of the most precious things we can do is also think about dreaming or the imagination as a support structure. It is something that is rudimental to our existence.” Rory Pilgrim

When I was 10 my brothers and I built a raft. I have no memory of how we started, although I suspect it was from laziness: a derelict half-boat set adrift by some other sailor on the lake and found by us among the pontoons. We captured it just in time to lash the rotting planks back together and haul new wood from land to make it last another summer. I can see us wading waist deep, hammering, knotting rope, balancing on one foot and falling into the lake, and somewhere in the vivid picture of the waves and the light glinting is a thick red book bobbing against the wood like a tiny tugboat. Books do not float, so I do not know how this could be. But there was a book, it was red, and it was discussed. There was some acknowledged mystery, and I am sure if I asked either of my brothers what book it was and what author they would say they remembered nothing but the pages: how limp they were with the weight of water but how the book refused to sink.

Tonight, contemplating travel across an ocean, I sat down to confront paralysis about my itinerary in England. Every week I stare at maps; I draw circles and arrows, I zoom in and zoom out, and try to imagine distance and time, discomfort, sublime views, possible rain, and lost luggage. I look at pictures of the places attached to the names on small screens and large and then ask myself why should I even go there if I’ve seen it already, glowing and lovely on Instagram – shouldn’t travel be like unopened gifts? Tonight’s indecision led me first to South Downs, then to Sussex, which led me to Eastbourne Arts, which led me to The Turner Prize and to Rory Pilgrim’s interdisciplinary performance piece, Rafts, which I watched, mesmerized, from beginning to end, an hour and twenty three minutes (and no itinerary was settled…).

I had never heard of Rory Pilgrim. But as I began to research and learn about their work I was drawn into a sensibility I have not experienced before. Pilgrim comes from a family of caregivers, with a father in ministry and a mother in special needs education. The artist brings to artmaking the lens of ‘care’ in a way that uses vulnerability and emotion as a painter would use color and paint. The result is an ensemble performance of voice, poetry, visual art and song that is deeply affecting. Woven through the narratives are themes of our relationships to trees, to loss, to the abandonments of human attention configured by technology – and the extremes of alienation experienced in pandemic. The young singers have unearthly beautiful voices, and perform with an unflinching lack of apology for their vulnerability. To hold this level of presence under a spotlight on a London stage is a radical act. How they got to this place is revealed in the eight minute film from the Tate about the ensemble’s process of connection and trust building: Activism can come from a space of joy. How, I wonder, can I move with this kind of authenticity and risk in the tools of my own work?

The context for artists working in the care paradigm is political: the disintegration of the British welfare state. This would not be usually top of mind for a tourist looking for escape in King Arthur and relics of Bloomsbury. But since March 2020 I have lived obsessively in movies about Britain. My interior landscape is furnished not just with the fine damask of Downton Abbey but the grime and soot of Peaky Blinders, and most recently 1980’s Margate, poignantly rendered in Empire of Light. There are brilliant actors and moments of deep humanism in these dramas, which deal with the tolls of war, mental illness, class and injustice. During pandemic many articles were written about the influenza of 1918. They often noted how nothing could be found written about the emotional aftermath; it was as though the years had vanished. As we know, witnessing the breakdowns in our schools, our streets, our political discourse, the ripples from our own pandemic continue. It is comforting as I look around a city still aching with disrepair to see other parts of the world acknowledge the breakage and the mending still ahead.

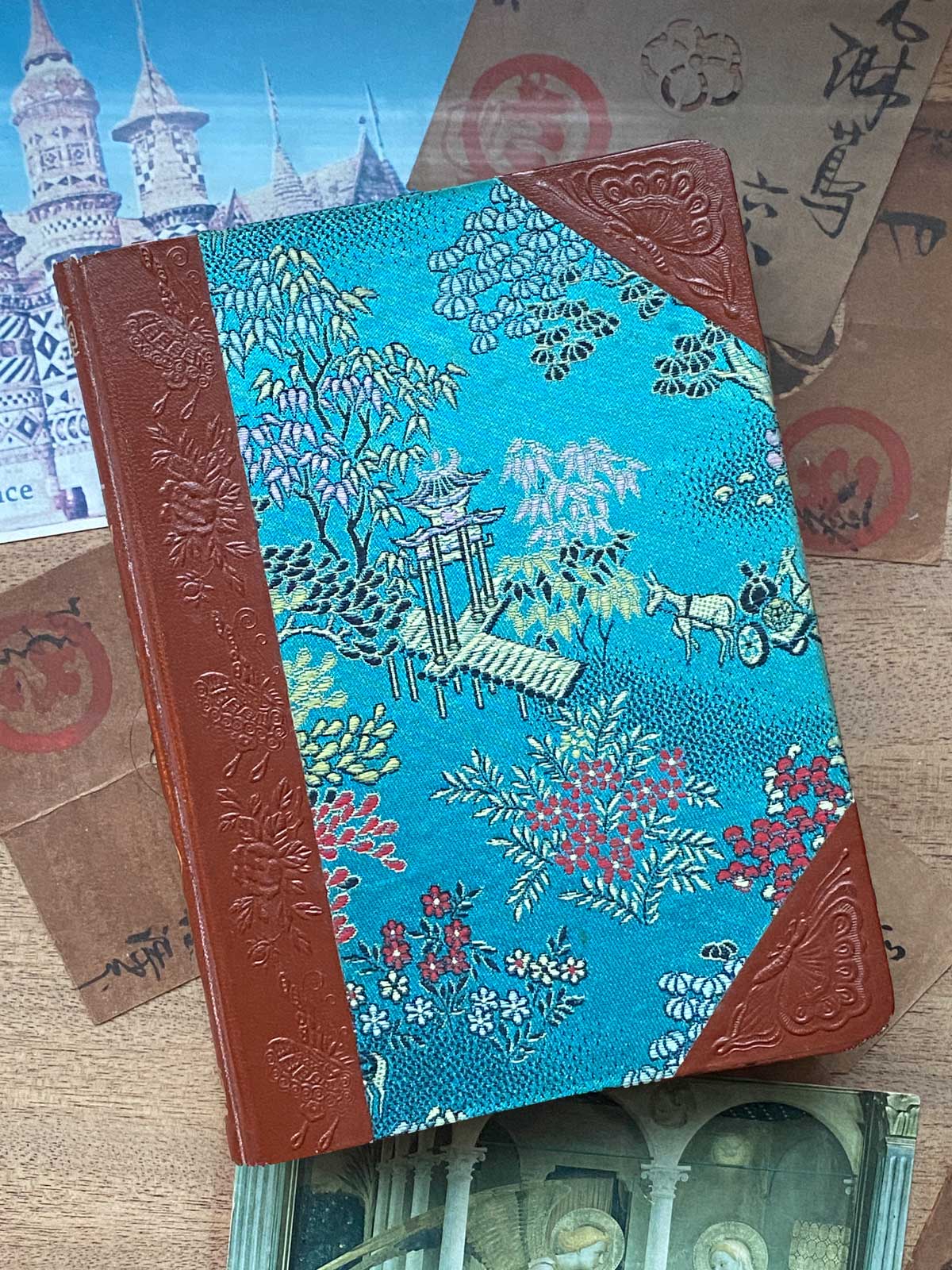

Did I mention the journals? I have unearthed not just my own journal of traveling to England with my mother in 1969, but my mother’s parallel version. Mine is lurid blue satin with gold embroidery, and hammered leather corners, purchased in Amsterdam. Hers is a stained steno pad. The journals are a marvel, which I will share more of in the future, but for now I am thinking of a church on a hill. My mother’s atheism was thoroughly tested in Europe. Somewhere in France she announced that she would not walk through one more arch or stop for one more statue of Mother and Son. But at the end of our British journey in the countryside near Burford we came to a church. It was unvarnished, whitewash and rafters, and the shapes of the hills echoed in the simple curves of the stained glass. My mother walked to the door and stopped on the threshold. She said, after a moment of silence, “This is a praying church.”

That’s the sense Rory Pilgrim’s work left me with, and why England keeps calling for return.

Solstice

In just two days the Solstice arrives, and I welcome the brighter days. To celebrate, SAM Gallery and Shop is offering an after-hours shopping event December 21st, from 5-8 PM. There will be free gift wrap services, light refreshments, and holiday cocktails at the cafe. I hope you will stop by and enjoy the festivities. However you celebrate the season, I wish you peace, light and joy!

Leave a Reply