“All that is solid melts into air.” – Marshall Berman

“Stories are for joining the past to the future. Stories are for those late hours in the night when you can’t remember how you got from where you were to where you are. Stories are for eternity, when memory is erased, when there is nothing to remember except the story.” – Tim O’Brien

My studio window faces east, and in the winter a plume of silver rises from my neighbor’s chimney, blooming upward against the dark scrim of evergreens until it blends into the clouds above the little lake hidden beyond. Although it is beautiful, I can’t look at an arabesque of smoke these days without thinking of California and the fires. In the morning as I sit to meditate and be grateful for the day my thoughts run beyond the borders of the visible. I shut my eyes and my mind fills with headlines, a tickertape of catastrophe.

2017 brought a harrowing onslaught of natural and unnatural disasters, from tropical storms to earthquakes to fires to the drastic political campaign to dismantle our national parks. Some disasters seem distant; others, depending on the luck of personal geography, may infiltrate every pore of your skin and fill your hair with ash. I live in the still-damp terrarium of the Pacific Northwest, but my family’s roots are in California. All through this late summer and fall I was on high alert with worry, thinking of my cousins. In Seattle and the islands the sunsets were spectacular. The smoke from the northern fires in Canada and to the East filtered into our native silver light and turned it tangerine. Leaf-shaped ash settled on the windowsills.

As the fires in Sonoma spread, an email chain of 19 cousins sprang up to share news of evacuations. In Santa Rosa a cousin’s house and car burned to the ground. In the midst of worry and sorrow we turned instinctively to history for solace and began to share the legacy of family stories. Each telling of the family myths had been remembered differently, and changed when retold. Did grandma McCarthy really fall out of bed when the San Francisco earthquake struck? Do we believe that patrician matriarch with white hair was ever thirteen, and wringing her hands in the garden and reciting poetry to calm herself down – or is that Irish hyperbole? The fires came. The family lived in tents in Golden Gate Park. For how long, a day or a week or months is unclear, but we needed to believe this story, because it meant that there had been worse, a fire and an earthquake, and we come from a resilient line of people who survive catastrophe, and quote poetry while doing it.

The fire stories in the news all recite a version of the same moral tale. The person, chased by flames, throws a few things into a car or backpack as they run for it. They lose everything, but they are grateful for their lives because that’s what’s important. Those of us reading are prodded to nod in agreement: yes, look how their values clarify in the heroic emergency, all that matters is the life force and continuing on. And yet. In the lengthening thread of my Irish cousins’ correspondence about catastrophe, objects began to emerge. Everyone, it seemed, had some heirloom tucked away, and we began to trade pictures. A sterling hairbrush, a mirror. Grandfather’s copybook. A gold watch and chain inscribed with three different initials dating from 1848. Byrne, Rooney, McCarthy: Éire. An entire island comes attached to these names.

Objects matter. They hold memory, or, as Fennel Hudson put it, “fine things are reservoirs for the heart,” whether they are engraved in gold or ghosts of silver halide on stained paper.

As today’s younger generation embraces a vogue for minimalism and non-attachment, consider that it may be born of necessity as much as fashion. The environment is imploding, the seas are rising, the idea of a “job” or “security” or “family” has been replaced by gig, by reinvention, and by never getting married because you never know when change might happen. At the same time as all that is solid melts into air, global culture has embraced images as never before. How many thousands of times a day does someone say “just like a movie,” “postcard perfect,” “Pictures or it didn’t happen….” The line between real and replica has never been less clear. You could call this delusion, or you could call it a fine and logical survival mechanism. It is human to want something to hold onto, and when the actual world is looking shaky the idea, the image, may be that something. If you are standing in the smoking ruins of your home it is the idea of home that will move you onward to rebuild.

All the same, I do not want to live in a world built purely on sentimental remembrance. Take the Arctic Wildlife Refuge (oops, sorry, it’s been taken already) or the Bears Ears National Monument (oh, that too, hieroglyphs and all–). Wilderness is our image bank as a collective consciousness. It’s the idea of the wild and all that it contains. But if wilderness becomes a denuded moonscape of oil rigs the idea itself will die, and with it the collective soul. Then we have only the Disney version sold back to us as a movie, in a sorry attempt at pacification through images and a soundtrack to consume.

My recent work is preoccupied with this tension between the ideal, what I think of as the archetypal food of the soul, and the unironic in-your-face calamity of the present. I am never drawn to overtly political art, but as a politically engaged person it is always present as subtext in the images I make. Politics is power. The distribution of power and its effects on the landscape change what we see and how we see it. As what we took to be solid melts into the sea or goes up in smoke, the importance of images becomes even more vital. Images are our bank for the spirit, our place to store remembered bits of Eden, against getting tired, and forgetting.

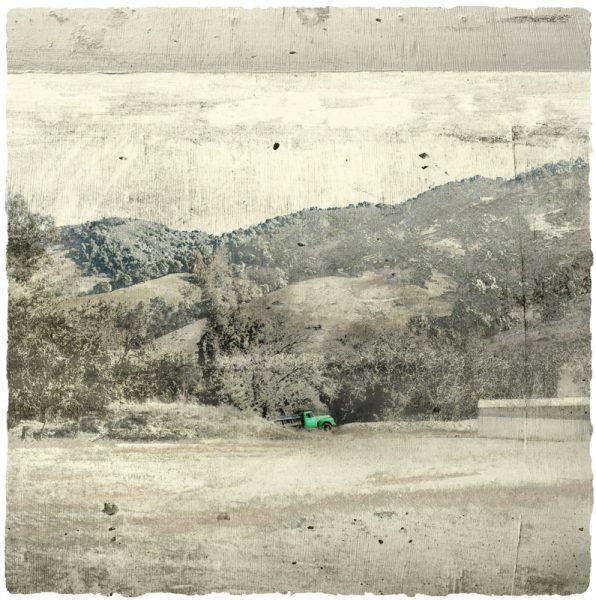

For instance, this place. It’s just a green truck, in the hills. But that day the hills were green and the pond was full and the wind blew softly with no trace of heat. It’s a place you might want to return to from time to time.

Ahead, I hope you will save the date, March 3rd from 3-6 PM, for the opening of Industrial Pastorale at Perry and Carlson in Mount Vernon. This will be my first solo show in several years, and I am very excited about the new directions of the work. You can see glimpses in progress on my Instagram and Facebook.

If you are interested in purchasing work you may contact me directly for inquiries if something you like is not listed in my shop. Many of my larger prints are now on SaatchiArt, or you may find them at Seattle Art Museum Gallery.

Wishing you a time of peace and renewal in the season of the Solstice.

Iskra