New Work Influenced by “Monet at Étretat” at Seattle Art Museum

This July I made a visit to the exhibit of Monet at Étretat at SAM, and came away affected by it in ways I could never have imagined. Of all the art movements I have studied and learned from, Impressionism is my least favorite. As a student intern in the 1980’s I was assigned to guard the Henry Gallery’s exhibit “American Impressionism,” and this may have played some part in my disaffection. During those months I leaned against a wall for hours staring at a painting of blurry women in bonnets and skirts sailing down a dappled river until the entire art universe seemed to condense into one long sugar high of cotton candy. Even though it was the height of the women’s movement (or perhaps because of it), I found myself rejecting most of the exhibit, and with it most of what was commonly identified as “Impressionism,” for its “femininity.” There was a sense of stifling romance and bourgeois comforts that seemed completely alien to my own experience and to the times. Instead, I found my heroes in the Bay Area painters like Diebenkorn, Nathan Oliveira and David Park, and graphic artists like Ben Shahn. When I worked with figures I wanted to be as crudely elegant as possible, with as few strokes as possible. “Romance,” or “the Feminine,” if acknowledged at all, was hidden behind layers of denial.

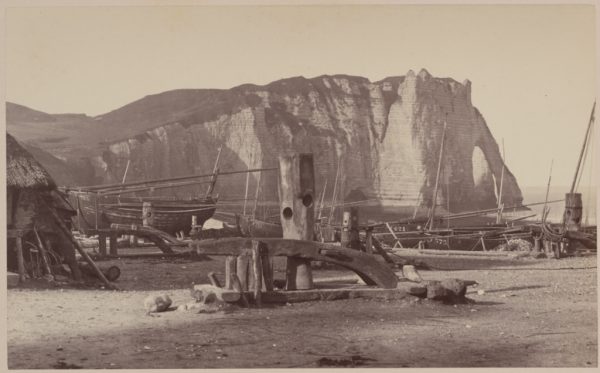

Add to this the factor of replication, and how hard it is to see a famous painter’s work freshly when it is reproduced on coffee coasters and umbrellas and shopping bags stretching out into infinity. I associate Monet with product, with an endless funnel of pink and white lilies and blue haystacks, and I have not looked at his work live in a museum in decades. Stepping into the intimate darkness of the SAM show was a revelation. Much of the exhibit is about context and history, and this sets the stage for the burst of color in Monet’s work that greets you at the end. Early impressionists were also collectors of photography, and the exhibit begins with a series of photographs that show the beginnings of influence between the mediums. The tiny albumen silver prints by Louise-Alphonse Davanne are mesmerizing. These images have an uncanny power relative to their size, and they transported me instantly into the middle 1800’s. I felt like I could smell the air and feel the sand of Étretat under my feet. At the same time the juxtaposition of the capstans with the cliff seemed completely contemporary, (and directly connected to my own obsessions with industrial structures, a comforting through-line across the centuries.)

The SAM exhibit includes a dozen paintings by Monet’s contemporaries. Although I regret to say I did not fall in love with Monet’s works, I did fall in love with Corot and Boudin, and in particular Corot’s handling of figures. One painting, “The Beach, Etretat,” (first image above) got me thinking about my own medium in a different way. With a few glaze-obscured strokes Corot describes a woman and child in a way that is timeless, accurate and completely abstract in its brevity. I came away wondering what I could do with figures in the mixed media of paint and photography that could speak to that image and how it burned into my mind. And Monet? His influence was the purity and alchemy of color itself.

Photographic Impressionism: The Immersions Series

For the next few days I walked out into the world with my camera and a new eye, asking myself what is “photographic impressionism?” How do you walk the line between romance and realism, nostalgia and now? What do we avoid when things are out of focus, and what do we see more clearly? At Golden Gardens, along the waterline, I found the same people of 1850’s France, but with less clothing. In the first weeks of being able to go out without masks, and with the sudden appearance of sun, there was a sense of wonder and euphoria at what, in summers past, would have been ordinary. I experimented with shooting scenes blurred and in focus, at low resolution and high, and back in the studio blended painted surface and various degrees of documentary accuracy to see how this changed the emotional content. How could I, in other words, find my version of Corot’s woman and child?