Over the President’s weekend I have been working on a series of street collages. Background reading that hovers, a guiding helicopter as I shuffle shards of color and type, is a book I just picked up at Elliott Bay called “Rapt.” Who could resist a book written by “Winifred Gallagher”? The name alone gives her instant credibility, but if that isn’t enough for you, she does have a thesis, and hard-won: “The quality of our lives is determined by what we pay attention to.” If you are a cancer survivor and you decide to write an entire book about this, I will most definitely tune in, with undivided attention. Although a quarter of the book is already dogeared with turned corners and notes in the margins, this passage in particular struck me:

“Just as bad feelings constrict your attention so you can focus on dealing with danger or loss, good feelings widen it, so you can expand into new territory — not just regarding your visual field, but also your mind-set. This broader, more generous cognitive context helps you think more flexibly and creatively and to take in a situation’s larger implications. …….when you feel upbeat, you’re much likelier to recognize a near-stranger of a another race — something that most people usually fail to do. “Good feelings widen the lens through which you see the world,” …… “You think more in terms of relationship and connect more dots. That sense of oneness helps you feel in harmony, whether with nature, your family, or your neighborhood.”

This idea affects me on many levels. February marks the recent passage of a marvelous Northwest artist and teacher, Alden Mason. I was privileged to take his last class at the University of Washington, when he was just beginning his artistic prime at 63. I remember working on a dreary watercolor of a nectarine, a plank of wood, a teapot and god knows what else on oatmeal paper in black gouache when I wailed to him to come and help. I don’t recall his exact words, but I will never forget his generosity and his wide yet intimate view. Each inanimate and dispiriting object in my still-life was a character, in relationship — the plank with the fruit, the teapot with the slanting light from the window, the floor with the paper and its hundreds of tiny fragments of non-archival woodpulp (oatmeal paper! bring it back! humble us as we work on 100% acid-saturated disintegrating fragments of trees, and teach us to be free!). Alden was not a painter who was trying to “make good compositions” or even good paintings, for that matter. He paid attention to each blob of color, each squiggle of paint, as though it was a friend to carry on with, to converse and conspire and perhaps float down the Amazon with, looking for birds. He passed this jubilant anthropomorphism on to his students. In that moment as he stood by me looking at my watercolor what had been a “problem” to “solve” became a cocktail party full of fascinating characters who’s story I wanted to hear. With that frame of reference the painting took off, and in a quiet way my life changed.

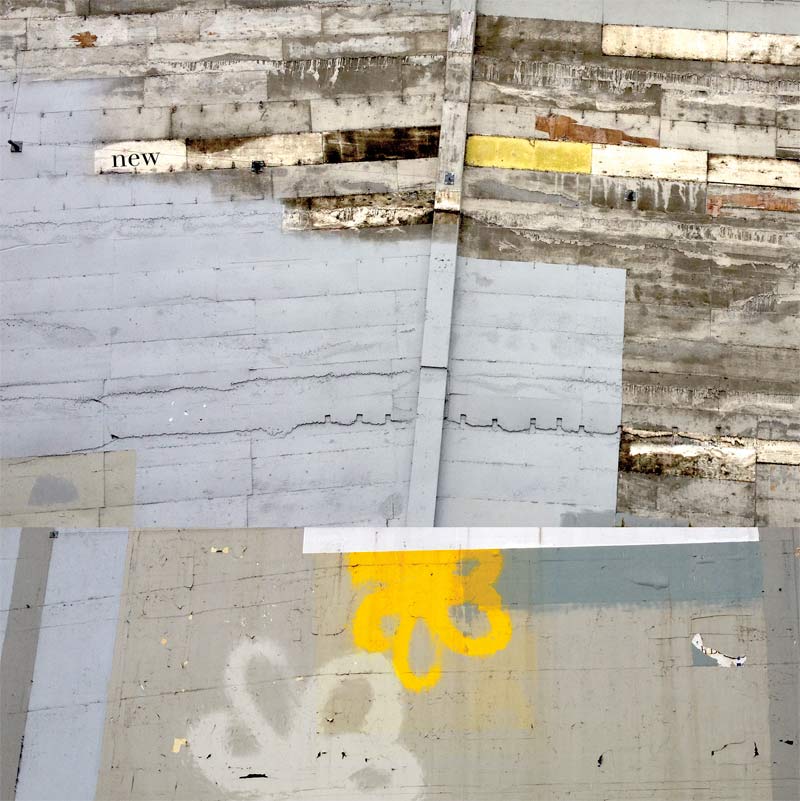

Composition is, in essence, the practice of paying attention, and becoming conscious of what you pay attention to. When I walk down the city street an overwhelming flood of sensory imagery pours towards me. How do I order it? Do I look for signs of the modern saber-tooth? the predator of worry or an actual assailant? for signs of rain or for police who will tell me to buckle up whatever untoward sensibilities have gotten loose? Or do I follow my native tendency to read the random like a book, and to connect the dots of the particular into the bigger unfathomable poem, as it changes, as I walk?

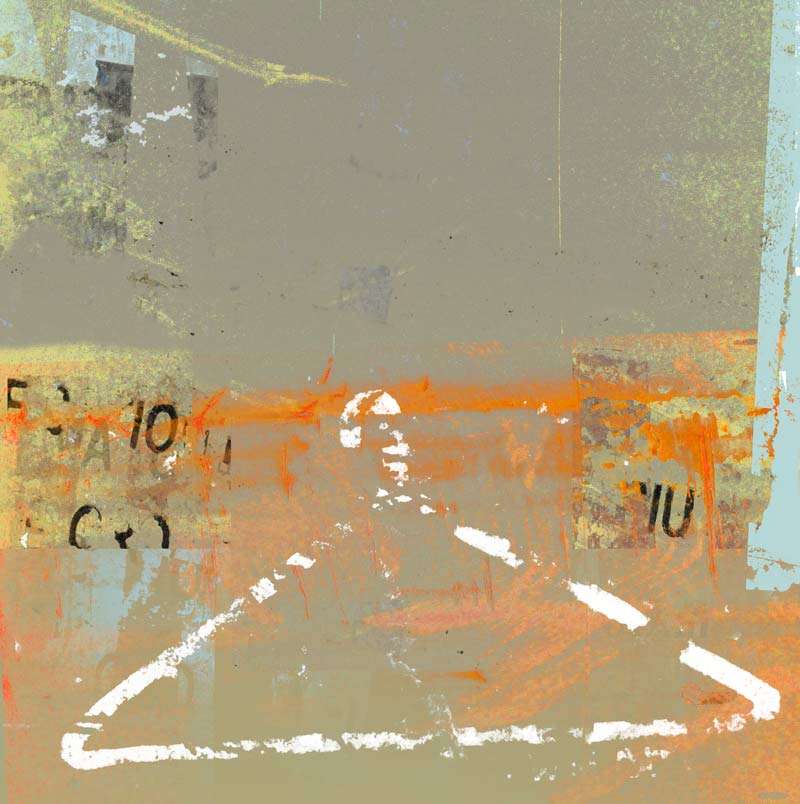

After these urban walks, when sitting at my computer with (conservatively speaking) — three to five thousand collected images of a lifetime of walking — I am confronted with the question of how I choose and arrange and then navigate the variations available in Photoshop’s magic trunk. How wide is the net, and how deliberate is the choice? Do I focus on color, or shape, or opposites, or harmonies or atmosphere or conversation or pathos or humor? And in choosing, what balance do I also choose, how do I weight one over the other? Lastly, or more properly firstly, how can I access a spirit of open good will that rewards possibility and does not punish the hours of blind alleys and disasters? “Rapt” is the state I have always sought in making art, and yet the process of decision making can easily shatter it.

Sunday I took a break from the studio and went to a demonstration against coal trains at Golden Gardens. At the end of the demonstration, when the polar bear with claws made of recycled tires had slunk away and the men with daisy heads on stilts had gone back to normal height I paused with a friend and watched the trains rush past above the playground. I instinctively started photographing the moving graffiti, which is as much a part of the landscape of the park as volleyball or the grebes. My friend’s daughter shouted after each train, “Is that coal?” “No, just oil,” we said. And although I was standing there and being sociable I was also transported to trainyards in another time under the dark of the moon: I’ve ridden the rails, climbed on with a backpack at four AM long before the invention of fancy spray cans. Politics and aesthetics gives me a lot to think on. In scavenging the street there is this paradox: the graffiti artist defaces the wall of the property owner, the artist captures the defacement and…..offers it back. Yes, it is for sale. You could call this the art of revenge. Or poetic opportunism, if you are feeling generous.

- “Approaching Spring,” archival print, © Iskra Johnson

Recent walks have been under deeply pessimistic skies. Seattle is known for its one hundred words for bleakness, and Paynes and Davey’s Grey would be among them. Yet a person’s mind turns to possibility. And hope. These collages are composed of pieces of the world bordered by Seattle’s Fifteenth Avenue East and First Avenue, and north to south, Eighth and Aurora and Jackson Street, with a lot of time spent in the parking lot at 2nd and Pike.