Today I am holding a New York Times in my hands. My fingers have a faint imprint of ink on them; I can smell the pulp, slightly dampened by rain even through the blue plastic sleeve that encased it this morning. I read the text, but mostly I look at the pictures. I relish the signs of reproduction: the irregular halo around a dancer’s silhouette, the soft blur on a soldier’s boot, granulated dots across the Japanese grandmother who cradles a child, her expression unreadable behind a white dust mask.

Every few weeks I sort the collected papers and cut out images. Some I put in folders which I label and promptly miss-file: “hands,” “people with hats,” “bank criminals and football coaches,” “people shouting.” Where do you file “tribal man holding a translucent scarf against his body”? Or “boy sweeping the sky?” Some clippings I put on my bulletin board until they become so yellow I have to hide them. One particular photograph teeters on the edge of archival viability now; I never get tired of (or less disturbed by) the man in a turban praying in a bombed out mosque. The walls are the palest aureolin and blue, and the blue of the sky now blends with the walls. He keeps praying; he was praying seven years ago and the bombs keep falling, shifted a few miles to the north.

In contrast to this, this living with fragments of newsprint tucked in drawers and pinned to the wall, there is TV. I walk on the treadmill at the gym and a newscaster pans excitedly to a video from Sendai. The video has been shot by a man in his car as his car is engulfed by the tsunami. Water spatters on the window. The announcer exclaims again and again, “These are stunning images!!” The man in the car is having an experience. We, as we exercise, are having stunning images. The newscaster bounces on his toes, practically panting in anticipation of the next new video. The man in the car is a true “content provider” offering up his suffering, turned into a marvelous adventure. I can see the same thing on my phone if I like, while preparing to drift off to sleep. I can play the tsunami, and then set my alarm.

This is what the human condition, ie. “news” has become. It is everywhere all the time, in our eyes and ears instantly, real time or instant replay, on demand, however we prefer, no matter how close or far from us it is happening. The way I receive the news affects how I absorb it. Although I was riveted for thirty seconds watching CNN how long will I remember the man who’s car is going down under the tsunami? When will it begin to blur with that fantastic viral U-tube of the guy in the carwash?

A few days ago I opened the Times to a black and white image of a bowl of ink on a table. Beneath the bowl inkspatters and scribbles mingled, and in my mind I added thumbprints, although the thumbprint is far too precious to toss away on a table, as it was the vote of the Egyptian people. I lost the clipping, and rediscovered it online in color. Now I see that the ink is a brilliant fuschia, and the photograph, by the astonishing Ed Ou gathers a whole new poetry in color. But part of the impact of this picture is that I first saw it in black and white and held it with my own hands, and touched it. It acquired a talismanic quality in memory and as I tried to recover it, and interestingly, no amount of keyword searches unearthed it in my quest; I had to go through the archives of the New York Times online.

I went to a talk by a meditation teacher last week. Serene, unassuming, and smiling like someone who might be selling you yarn at the knitting store, she delivered a powerful talk on holding the suffering of the world. At the end of a lengthy discourse filled with Buddhist terms like sila, punya and mudita she said almost offhandedly, “I hold my laptop, and there they are, the tiny people on the screen, running from the ocean, lying on the battlefield, cowering in front of a tank. Don’t you just want to pick them all up in your arms and keep them safe?” Beautifully posing one of the most troubling questions of our day: how do we live with the news, keep some margin of psychic immunity and yet retain enough porosity in our boundaries to feel compassion?

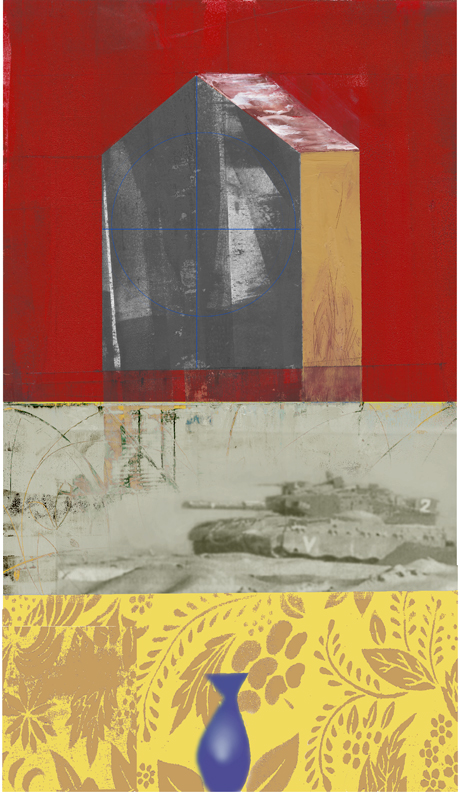

I created this collage at the onset of the second Gulf War. I am afraid it can be repurposed indefinitely and will never go out of date. I showed it to some friends and one said, “Oh, the vase is our denial, our domestic delusion that everything is all right if it’s all right here.” And then someone said, “No, it is the table and the vase that are real. They are our sanity. They hold up the world.”

The blue vase, I am sorry to say, broke several years ago.

Notermark says

“how do we live with the news, keep some margin of psychic immunity and yet retain enough porosity in our boundaries to feel compassion?”

It’s a consequence of both increased population and increased awareness of each other; and I don’t hear it talked about much.

It did come up with a friend the other day, but in a slightly different context. It took us a little while to get to the point which is so well articulated above. Thanks for posting this.