New Directions: Photographs of the Western Landscape

Are there affirmable days or places in our deteriorating world? Are there scenes in life, right now, for which we might conceivably be thankful? Is there a basis for joy or serenity, even if felt only occasionally? Are there grounds now and then for an unironic smile?

– Robert Adams

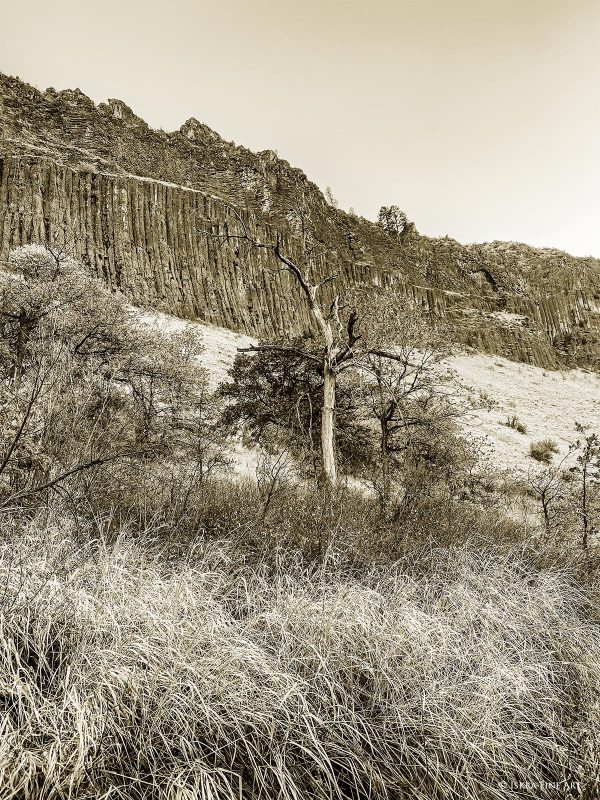

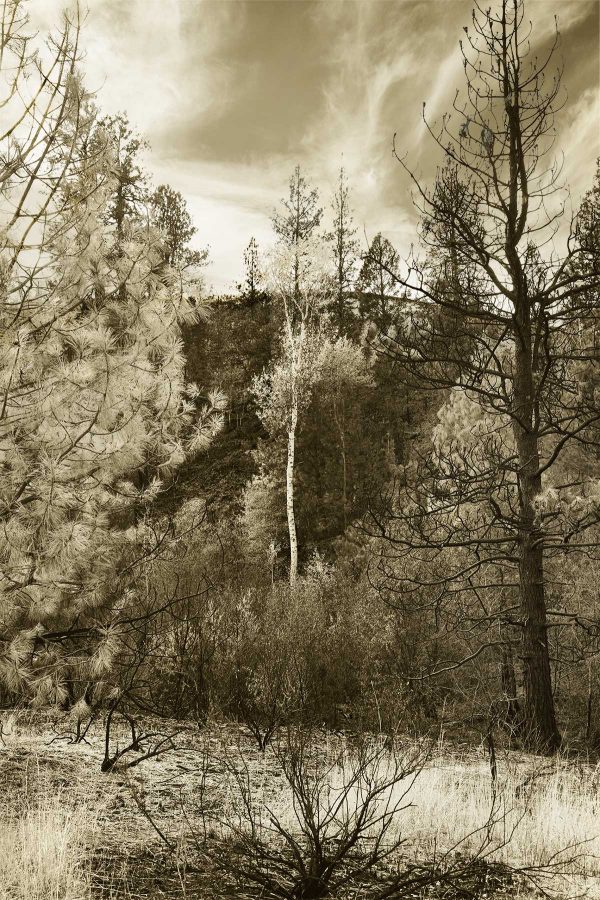

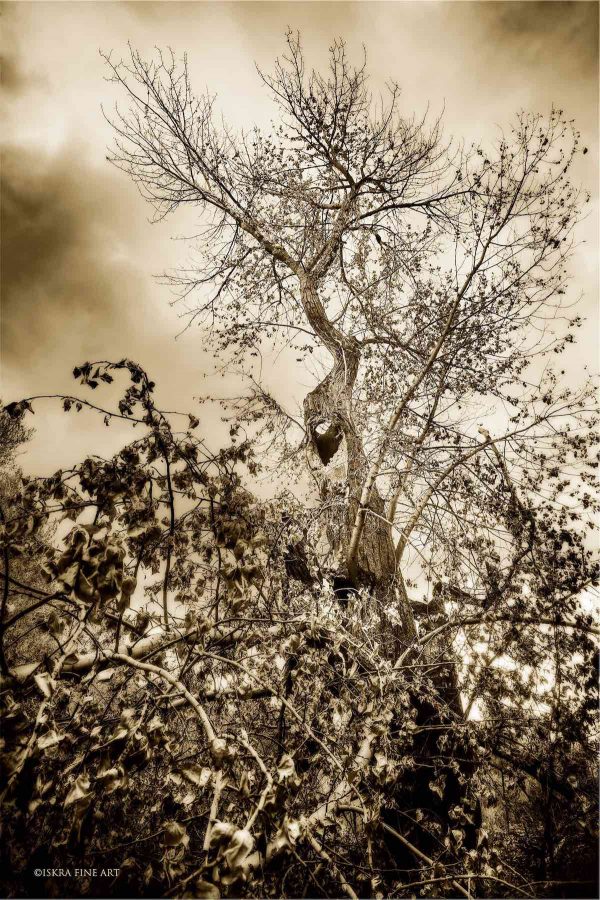

In October I found myself in the middle of an ocean of grass almost swallowed by basalt. I looked up at the black palisade of stone stacked against sky, a magpie’s wing shadowing the trail ahead, and asked out loud: “Is this a photograph? Should I follow this impulse? Landscape photography isn’t what I really do…..”

There was long pause as my walking companion vanished around a bend. The field caught the slant of afternoon sun like knife blades, each edge of grass etched against stone. The moment seemed to command me to see and record in a way I was not accustomed to – not with the collage artist’s eye for disassemblage, but as a witness to the exact 1/60th of a second in front of me. I raised my camera and started shooting, unsure of why, but thinking maybe I’d figure it out before the sun set.

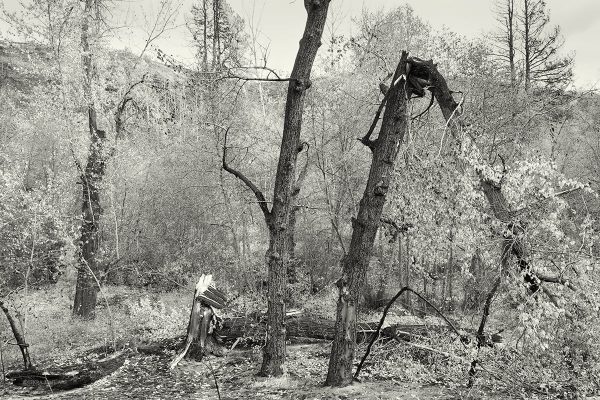

Although I have been obsessed with cameras and photography for much of my life, I have never considered myself a traditional “photographer.” Rather, I have seen the camera as way to inquire and to be present in place. The images made have always been secondary to the experience that looking through a lens affords. The technology of f-stops and aperture and ASA, the confounding dials with microscopic lines between here and my destination, and the chance, in analog days, of a precious 36 exposures tripping on a sprocket, all seemed to require a full time German in residence, and I am much more Irish. I have always been immune to systems, and I suffer from profound dyslexia when it comes to math. Someone asked me recently if this new series of landscape photographs was made using the “zone system” and I had to check my voluminous and completely disorganized notes – oh yes, that. My process is intuitive, and overlays multiple systems based on the aesthetics of printmaking and drawing.

In making photographic prints I am looking for luminance and iconic form, and a sense in the body of being there. Are there ten shades of gray from white to black – who cares? Does it feel and look like memory and the way the air moved? Can I smell the smoke in the air, or the sage, or hear the sound basalt makes as it cools down between late afternoon and evening?

I’ve got history with the West. I spent half my childhood on a ranch in the shadow of Mt. Rainier. The sprawling plateau marked a gathering place before the mountains, and the long ascent across the pass. Although the ranch was technically “Western Washington,” culturally it was of the East. I went to bible school, baked pies for 4H, diagrammed the parts of horses and got the green and purple ribbons for my riding skills that confirmed that I did not really belong there: I was just a city kid listening in. I was usually, literally, on the fence, sitting and looking at the fields and seeing if I could spot a 4 leaf clover hidden in the mustard. One day when I was about 8 we hauled a trailer with some Welsh ponies over the pass to the Yakima River. As the adults did their horse trading I found my split rail and sat on it and fell into a reverie at my first sight of cottonwoods: silver leaves?! How could the wind turn leaves silver? Much later I fell in love again, in Taos, where the phrase “sense of place” first revealed itself to be a true thing. For many summers I traveled the backroads of the Southwest camping in a truck, immersed in the essays of Barry Lopez, Gretel Ehrlich, and Terry Tempest Williams. I took almost no pictures. It all seemed like it had been done before by famous masters of the Zone System, and the Ansel Adams postcard would be in better focus.

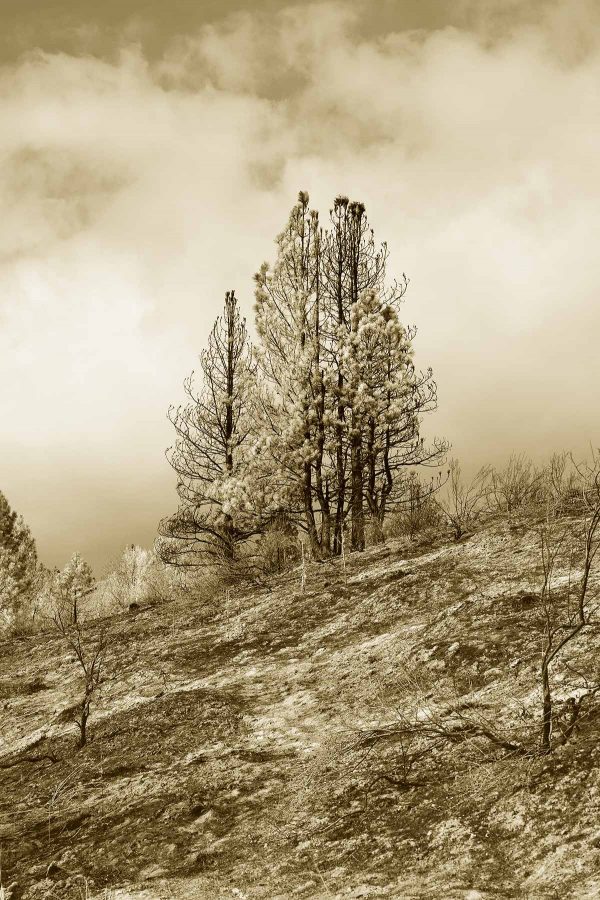

What I found myself unable to resist during my time in Tieton was the quietness of the spectacular. The scenes were iconic, but they had no famous names, and were not on postcards. I had the sense of seeing the land for the first time, with all the stammering of first romance. I had no intention of taking serious pictures, but once I started I couldn’t stop, and every turn of the road had the excitement of an assignation.

I used two cameras, my iphone 11 and a Sony Alpha a7R ll. The cellphone photographs have their own unique luminance and grain, and work best at 12 x 16 or smaller. The other camera allows images to go in some cases as large as 22 x 30 while still maintaining quality, and for canvas or wall art that will be viewed at a distance they can go larger. It is a complex process to go from a glowing hologram backlit on an LCD to an equally compelling “work on paper.” In the modern digital darkroom the number of ways to develop a print are endless, and of course I had to try them all. I spent weeks looking at how filters create their effects, experimenting with custom duotones, testing and testing. In the end I chose to limit the series to a range of black and white and custom-built duotones. I wanted the work to have a sense of history and discovery: an echo of Lewis and Clark, sending back notes from the trail.

Most of the prints in this series are now in my shop, and with a few exceptions, are available in both custom duotone or black and white. They are mean to live on the wall as salon style framed pieces, or as single larger focal points. They are printed, as my other work is, as limited editions. Due to the current WordPress settings for retina display this blog or the shop are the best ways to view the series. Right click to see images larger. To purchase, visit Western Landscape.

*Until January 2nd all shop items are 20% off.

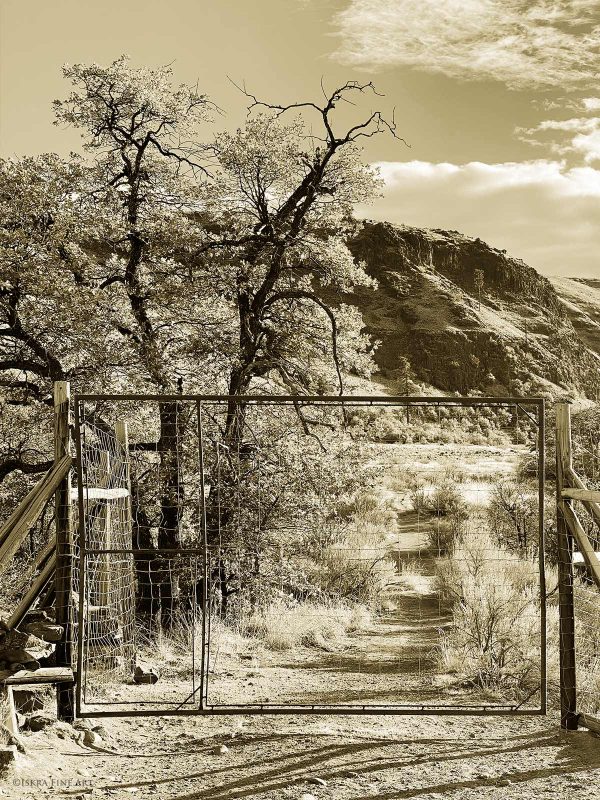

The gate has become an emblematic image for me during the pandemic. I don’t know about you, but I need to focus on the horizon. I keep returning to this archetype, and when I look at this scene it makes me feel a sense of possibility: entries to the beyond, protection for where you are. The horizontal version of this scene is available in Duotone or Black and white in sizes up to 24 x 33.

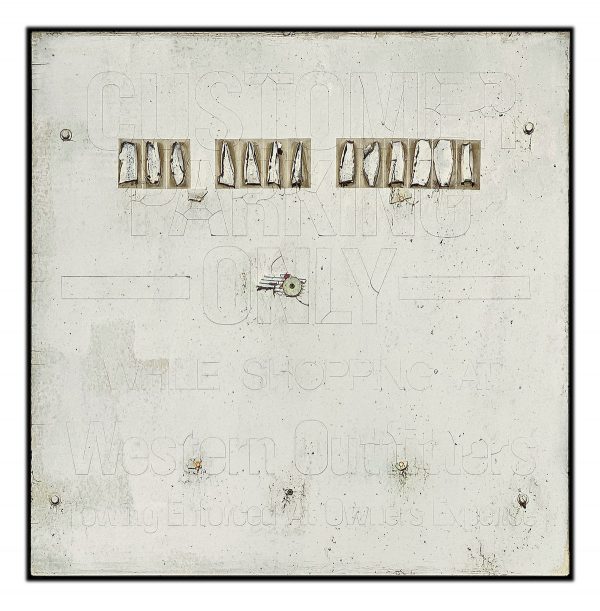

The last print in this series may actually carry some irony. “Nonverbal Verbal Communication,” is the title for this precisely observed sign outside a repurposed western wear store in Yakima. As a child on the ranch, this is the kind of place where I got the pastel pearl-button shirts and red cowboy boots that marked me as someone with a refined fashion sense. Dream on, cowgirls.

A note to designers: This work is meant to be lived with. Feel free to contact me for custom sizes and substrates.

Irza, The Supermelon says

I absolutely love how this portfolio captures the breathtaking beauty and serenity of the Western landscape – truly a visual treat!