“One must learn to float as words do, without roots and without watering cans. One must know how to navigate without longitude and without motor. Without drugs and without burdens. One must learn to breath like a wind instrument. The chord must be made of sand, the anchor of aurora borealis.” –– Anais Nin

“The term ukiyo-e, meaning “pictures of the floating world,” is a pun on a Buddhist phrase meaning “suffering world,” also pronounced ukiyo. Asai Ryoi defined the attitudes of the irresponsible but delicious floating world as “living just for the moment, focusing on the pleasure given by the moon, the snow, cherry blossoms, maple leaves, singing songs, drinking wine, diverting ourselves by just floating, floating, ignoring the pauperism that stares us in the face, refusing to be disheartened, floating like a gourd that drifts along with the river –– this is what we call ukiyo.” –– Yoshitoshi’s One Hundred Aspects of the Moon, by John Stevenson

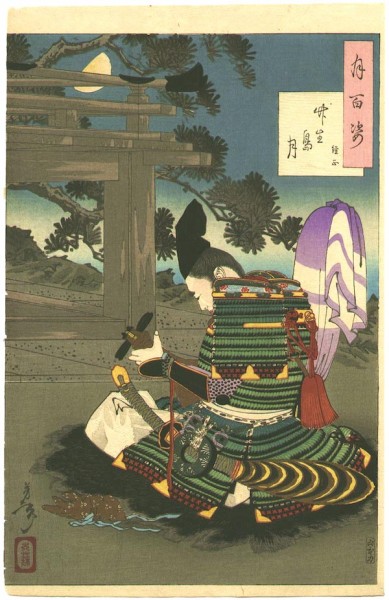

The inspiration for my latest series comes from studying ukiyo-e and particularly the life and work of 19th century artist Yoshitoshi. Outside of comic book historians and collectors of Japanese prints, this renowned Japanese woodblock master is no longer familiar to most North Americans. His career spanned a period in Japanese history of violent political and social upheaval, the Meiji Restoration, in which Japan began its transition from a feudal society to a modern one increasingly influenced by the West.

In his exquisite and elegiac woodcuts Yoshitoshi drew upon the drama and exactitude of Noh, and a wide vocabulary of historical Chinese and Japanese art styles. His subjects ranged from hyper-violent scenes of massacre, suicide and war, to serenely composed tableaus of domestic life in the pleasure quarters of early Tokyo. What captures me throughout his work is the sense of attention he brought to what is lost in the face of change. Whether depicting courtesans or samurai or the rising moon, his art honored the heritage of Japan’s past. Many of Yoshitoshi’s best images are a complex mix of brutality and meditative reflection. Visually his prints resonate both as theater and as elegant abstraction, in which every mark and shape fits like a puzzle with the whole. Today, as we face new waves of violence, displacement and relentless “progress” the essence of his work remains as relevant as when it first hit the streets of Edo over a century ago.

As a contemporary print maker working with digital media I always ask myself: Why this media for this subject? What can I do digitally that I can’t in some other way? And how can I provoke a sense of surface and tactile reality equal to work printed ‘by hand?’ I am in love with silk and with the pale translucence of woodblock skies. In all of these new pieces I imagine that I am working with fabric or fine rice paper, and that even as I may use a digital method I am holding a fine hake brush as I make the sky. Just as Yoshitoshi’s work existed as prints I want these to exist in the same way, as works on paper telling a story. The subject of my story is how we navigate, how we learn to float, when the known world is slipping away, when industry is becoming antique, when human reality is challenged on every front as the camera and the computer mediate our sensory experience. I was fortunate to have a friend who took me down the Duwamish River in a canoe, and many of the photographs embedded in the prints were taken on that trip, eye-level with the river and the great ships and barges that make the river their floating home.

Here is a selection of some of the prints on display. All of them are in limited editions of three, 24″ by 24″, printed in archival pigment ink on Hahnemuhle German Etching. The exhibit will be up through August 4th at the Alexis Hotel in Seattle Washington, 1007 First Avenue, 98104.

Except for the Yoshitoshi prints, all images © Iskra Johnson and may not be reproduced without permission. To see all the work in this series visit the new print portfolio The Floating World.

Leave a Reply