A visit to the Seattle Asian Art Museum, and a walk through change

In most museums sunlight is an unwelcome visitor. Light degrades what it warms. It is known to singe manuscripts until the edges crumble; it fades brocade and upends the narrative as the sword above the stag’s head turns from bloody to gray. Perhaps (though the back of the tapestry tells another story), it was not a hunt scene after all? History embrittles until truth hovers on the cusp.

Conservators learn: all interventions must be reversible. Do no harm, operate like a surgeon; use a fine brush, needle and thread, cotton soaked in brine. The ambered sky of a Dutch Harbor is lifted and revised– yet it may be revised again, when we know even more about the intended color of the afternoon.

Sunlight has no such mandate. Nor do the architects. In their contract skyscrapers need not return to 1930’s rooming house, or the even earlier logger’s cabin, nor must conservators be able to excavate the mastodon in the basement or lay out his bones in order. There is no past, all contracts are broken, there is only now, and it looks tall.

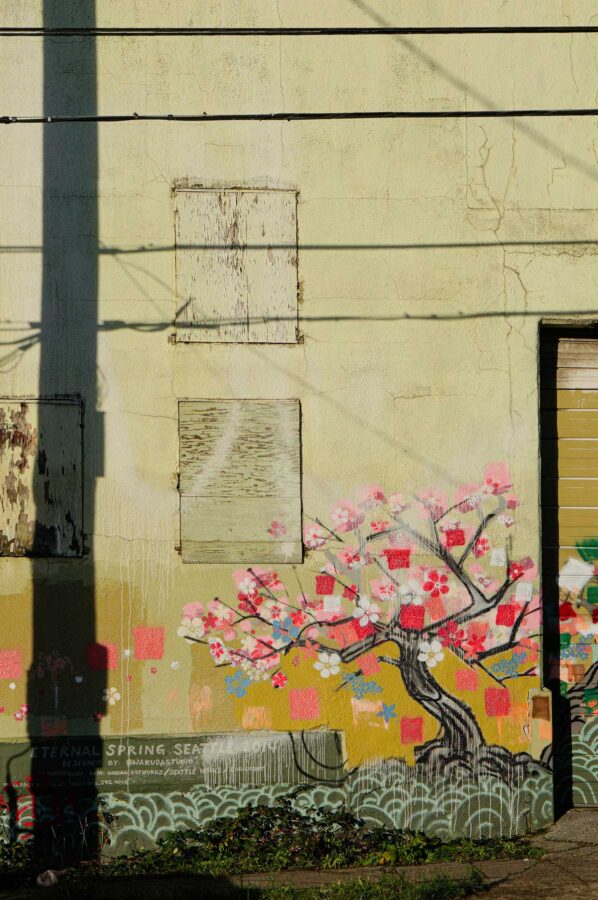

On Saturday morning I walked through the part of the city I call The Amazon, named for the river of money that flows through it. Streets were empty, stilled, and the only sounds were pennants rattling above construction sites and the thrum of machines that keep the buildings alive and young. The air was luxurious, as it has been all summer, but more particularly now as September days lead into fall. In the 13 years since I started documenting the neighborhood nearly everything old is gone. What is precious is vanishingly rare, and redefined by transience: the angle of light where it can steal through glass and concrete, a balcony still hugging privacy while another story waits to complete itself ten feet away. In a week the balcony will be in shade, eye to eye with a stranger’s living room.

The hardware store makes all the rest of the buildings make sense. I hear they are keeping the façade, which is like stacking the alps on top of a pristine lake and wondering why you can’t still hear the wind on the water. I reach for Edward Hopper’s hand, and though he rarely leaves the museum anymore he reaches back, and we stand clasped in homage to light on the side of a wall. “Maybe I am not very human,” he said in 1946. He meant he wanted omniscience, like the sun.

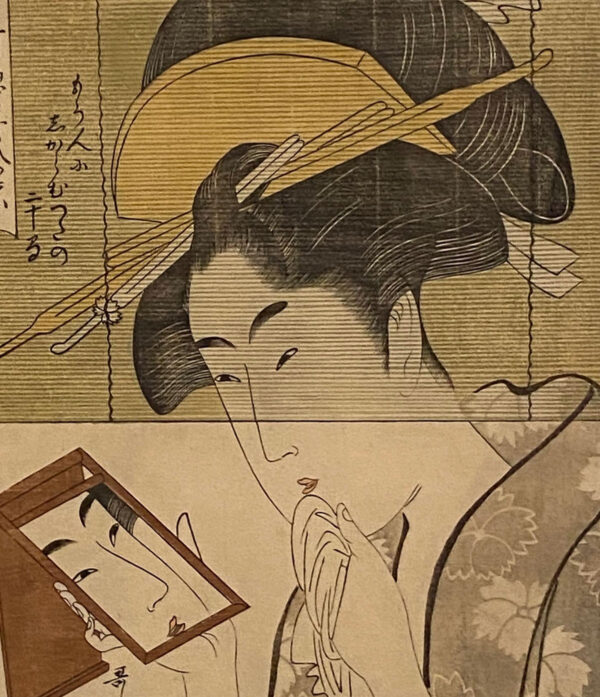

The most sunless museum of all is where the silks are stored. On Sunday I kissed the nose of the camels at the door and then fell into reverie at the Seattle Asian Art Museum’s Renegade Edo and Paris: Japanese Prints and Toulouse-Lautrec. I tried my best to give Lautrec his due. I understand what he was after, to appropriate, for his own rough hand, the Japanese language of space and refinement narrating the pleasure quarters of the Floating World. I looked at the pale beige paper and faded erasures between his dancers and I felt his pain. And then I went back to the glorious, quiet minimalism that defines the Edo. You best appreciate these prints and paintings by standing for a long time and looking without thinking, just inhaling the faint incense of mildewed tatami, charcoal and shellac that drifts up through the years. I have slept in temple inns with painted silk walls and they are humid, pungent with the sweat of monsoon and bodies and breath. In this exhibit you can smell history.

Then I went back out into the world, that museum of light where if you look up you can see change happening with or without your permission and with no promise of restoration. I walked through Chinatown and the edge of Little Saigon and past my memories of Japantown, an entire street of which seems to have been hidden. Perhaps I dreamed that restaurant, and the porcelain demons and cats and the saki bottles lined up front of the mirror, at the counter where we shared plates of eggplant tempura. The idea of place is being erased here in the name of many good ideas that seem, like Lautrec, to miss the mark and instead land somewhere in the country of colonialism. I wrote about what is going on in Chinatown recently, and why it does not stop breaking my heart.

My job is to make pictures, and they fill with more and more space as light burns memories in a jar. We are living in a city and a planet on the cusp, devoted entirely to the gospel of Proposed Use. This summer I walked with others through proposed clearcuts and then I looked back, returned to the river of my childhood, to the unclaimed woods that used to dot the city, to the old books, the ancient light and the rules of order and disorder. What is politics? Power, lack of power, permission, change. In the studio it’s always there, asking me to live with the conscience and contradictions of beauty.

All contemporary paintings and photographs © Iskra Johnson. Edo prints and painting details courtesy of the Edo Period, prints and paintings on display courtesy of the Kollar Collection at Seattle Asian Art Museum.

Milan Heger says

It was really beautiful to read your precious words, Iskra. Coincidentally, I read your blog first thing in the morning when the sun literally just touches only the places where it can get under the angle of September. Thank you so much. It all makes sense now.

Iskra says

I love that, “the light slipping under the angle of September.” Thank you Milan.

Kelly Lyles says

You are SUCH a strong writer, very evocative.

Parker says

Absolutely beautiful post. Made me understand the connections in your art even more.