An Evening at Town Hall in Seattle with Sebastian Junger

How long should the mood of Memorial Day last? It seems to have extended here past the weekend and the Monday holiday to Tuesday night, when I went to hear one of my heroes, war journalist Sebastian Junger, talk about near-death at Town Hall. His book, In My Time of Dying, is just out. I searched for reviews and was disappointed to find nearly identical 5-star summaries of content, 2-star disappointment from those seeking spiritual epiphany, and little else. A book like this is a contribution to our culture, crossing boundaries between the private and the public, between personal and professional, between atheism and belief, in ways that should, I hope, provoke far more meaningful reviews. That said, my thoughts here are not a “book review” as such, but a personal response from an artist and seeker who has been preoccupied with the borderlands of life and death for as long as I can recall.

Disclosure: I do not know yet if I will get the book and read every page. I read to be transformed. For me in this day and age the reading of a book may be secondary to the cultural moment in which it lives. Hearing an author in a setting worthy of years of solitary effort offers transformations of its own. Junger is a riveting speaker, and though my usual rule for lectures is, “If you are talking from more than 4 feet away and the room is warm I will fall asleep,” I was raptly awake for the entire hour.

Interspersed with Junger’s intimate civilian experience of the “bomb” of a ruptured aneurism, told with absorbing medical drama, were parallel stories of dodging IED’s and bullets in the conflict zones of modern warfare. The war correspondent’s stories were psychologically much simpler than the civilian’s: in war one was either killed, or just-missed death, and (innocently) preferred life over death. This is the readily accessible awareness of someone who has not actually witnessed death from inside the body. Junger’s personal story, however, was less reassuring: it left me shattered. No angels and no fairies and no sense that all is good in an afterglow of seamless gratitude. His experience rang uncomfortable bells of recognition that may be familiar to anyone who has explored meditation or psychedelics’ far edges. Letting go of the self is perhaps not all it’s cracked up to be.

No one else in the hall slept either, and when I scanned the faces behind me I saw a startling vulnerability and recognition as though somehow we must all have met before – At a grave? In hospice? Or chanting sutras in some temple? As I stumbled to the parking lot I was overwhelmed by vivid and unnerving images. I did not want to think of Junger’s all-too-real description of the abyss. I reached instead for another near-miss, his recounting of a woman in the town of Golden BC who woke from sleep to a loud explosion, a hole in the roof and a large meteor on the pillow inches from her head. She got up, made herself a cup of tea and sat in a rocking chair. She rocked and looked at the bed until morning. Perhaps the meteor, “the size of a large man’s fist,” its mineral glint radiating throughout the room, was placed by gravity like a gift of frankincense on a velvet cushion. Or perhaps it had been scorched black by travel’s friction and burrowed, like shrapnel, into a floral pillowcase in a cloud of feathers, in which case the celestial souvenir and the death of a chicken entwined. News stories do not focus on the chair and the cup of tea but on her cheery attitude:

“I never got hurt,” she said. “I’ve lived through this experience, and I never even got a scratch. So all I had to do is have a shower and wash the drywall dust away.”

In Junger’s telling, we don’t know what she really thought, we just know that she sat, and had a cup of tea. This is the kind of answer that the teacher offers when a student reaches a mystic milestone and doesn’t know “what to do with” the experience. In other words, they say nothing. If you are lucky they offer you tea and walk beside you for awhile. Tell you to breathe, and pay attention. We are still after all in the body, not yet disembodied vapor or ash, and for comfort we must come to our senses.

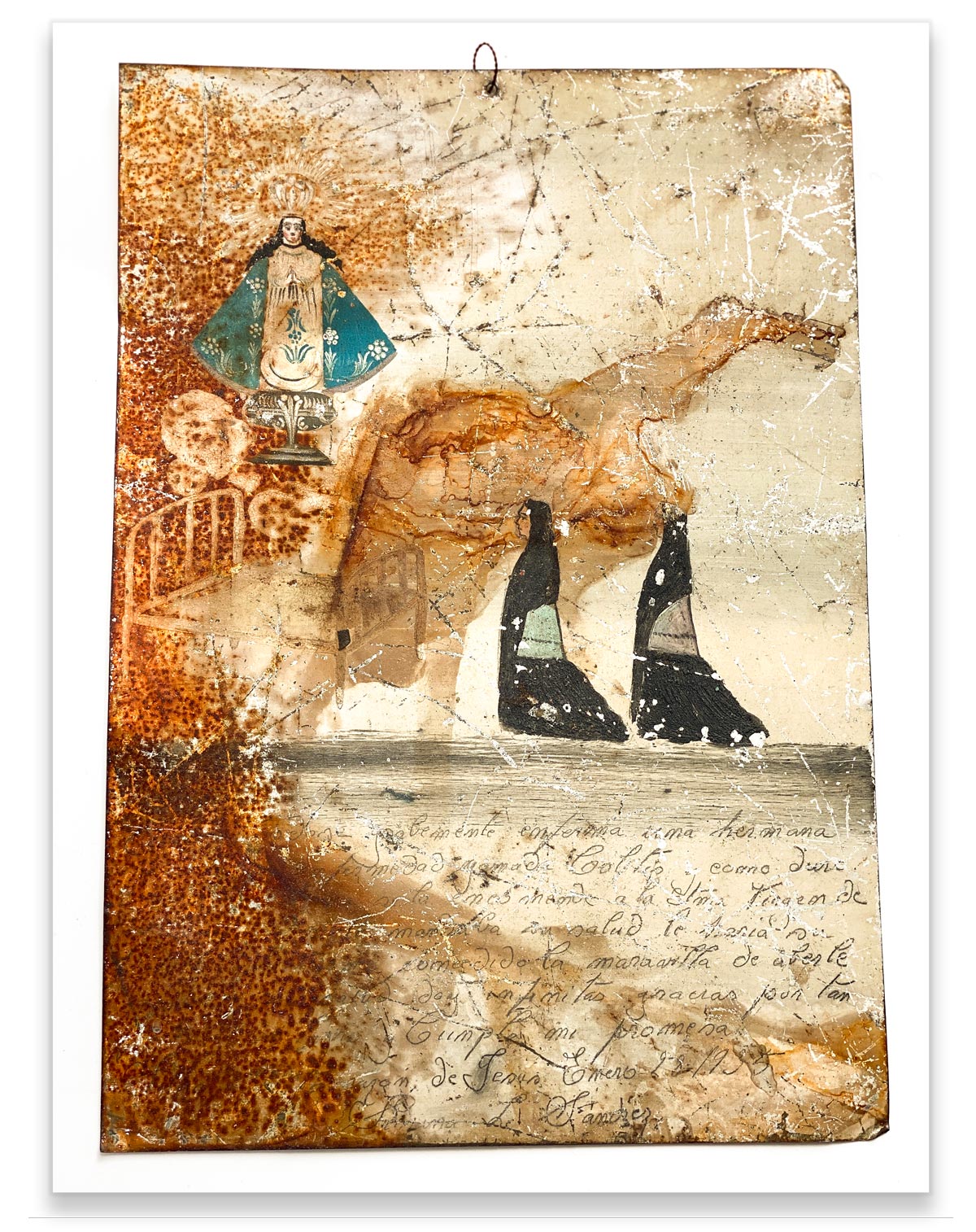

When in a state of confusion or distress I default to seeing, which, though sometimes confused with “thinking,” is one of the five senses and the one most directly connected to metaphor. Most people, according to a study now unfindable on Google (“Sorry art history buffs, but here’s an ad for Benjamin Moore blue sky paint, which is close don’t you think?”) – most people prefer a picture with a horizon line, green grass, blue sky and perhaps some pink. When faced with a crisis of meaning, or a blank wall above the couch, this formula has reassured supplicants for centuries, though it can veer into graphic depictions of pestilence in the form of Ex Votos. Here the format maintains the horizon line as a “ground” of parallel lines of text, in which the aggrieved asks for solace or forgiveness or gives thanks for the attentions of the saints.

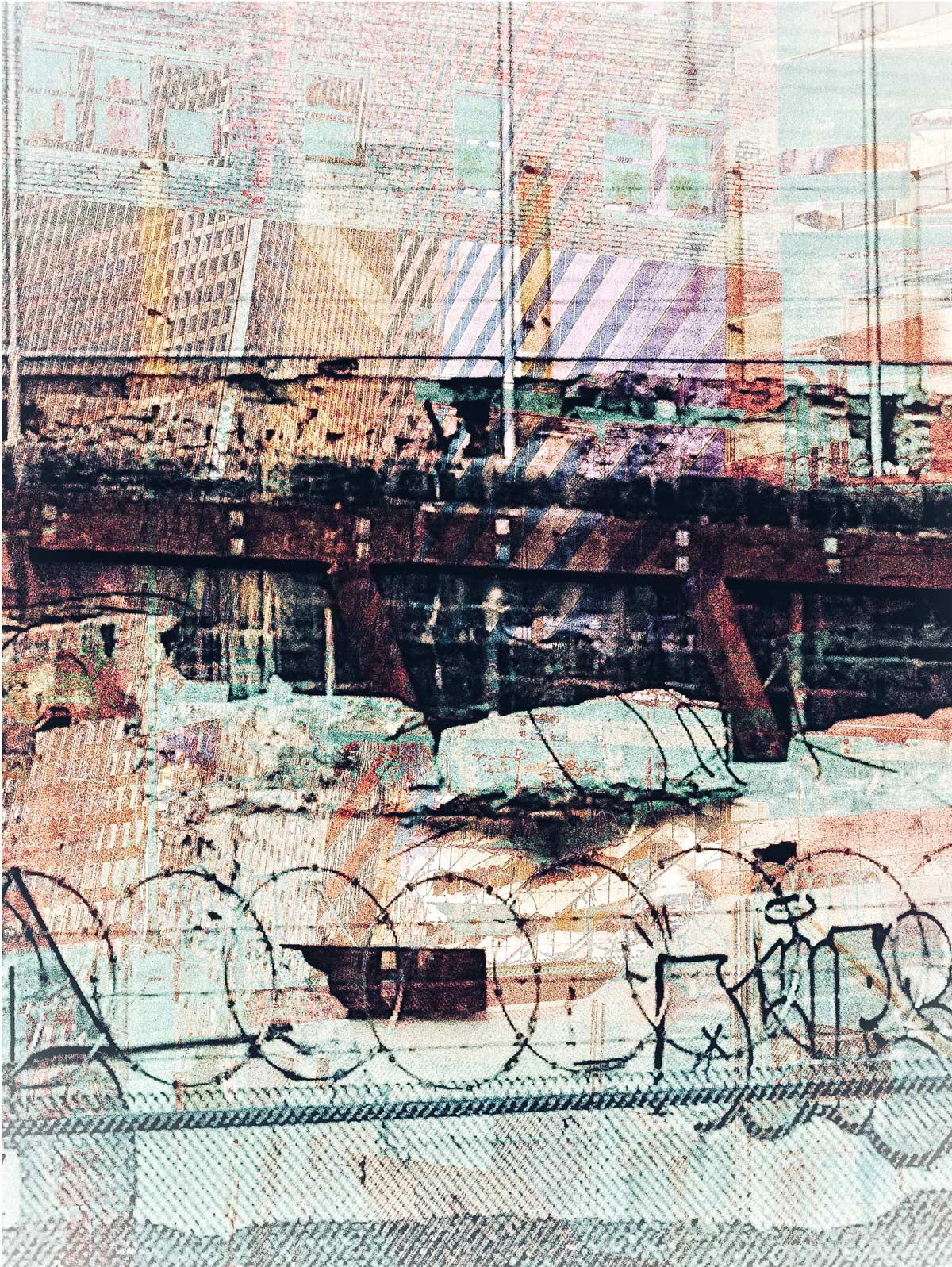

I don’t know if I have ever made a picture most people would like. When out of studio and in emotional crisis I reflexively illustrate my own prayers to the saints with the tools at hand, my iphone and collage software. For some reason taking pictures is my calming cup of tea. The life and death of buildings is my frequent proxy, and the area surrounding Town Hall offers many subjects. As metaphor, architecture is the body of a city’s people and culture.

Here, two views from the Virginia Mason parking lot. To the east, an open pit as though the aftermath of cataclysm, leaving bare the less flattering aspect of the Sorrento Hotel. To the north, a golden stair striped with caution bars. Who knows where it goes? If no heaven then perhaps at least a glimpse of blue.

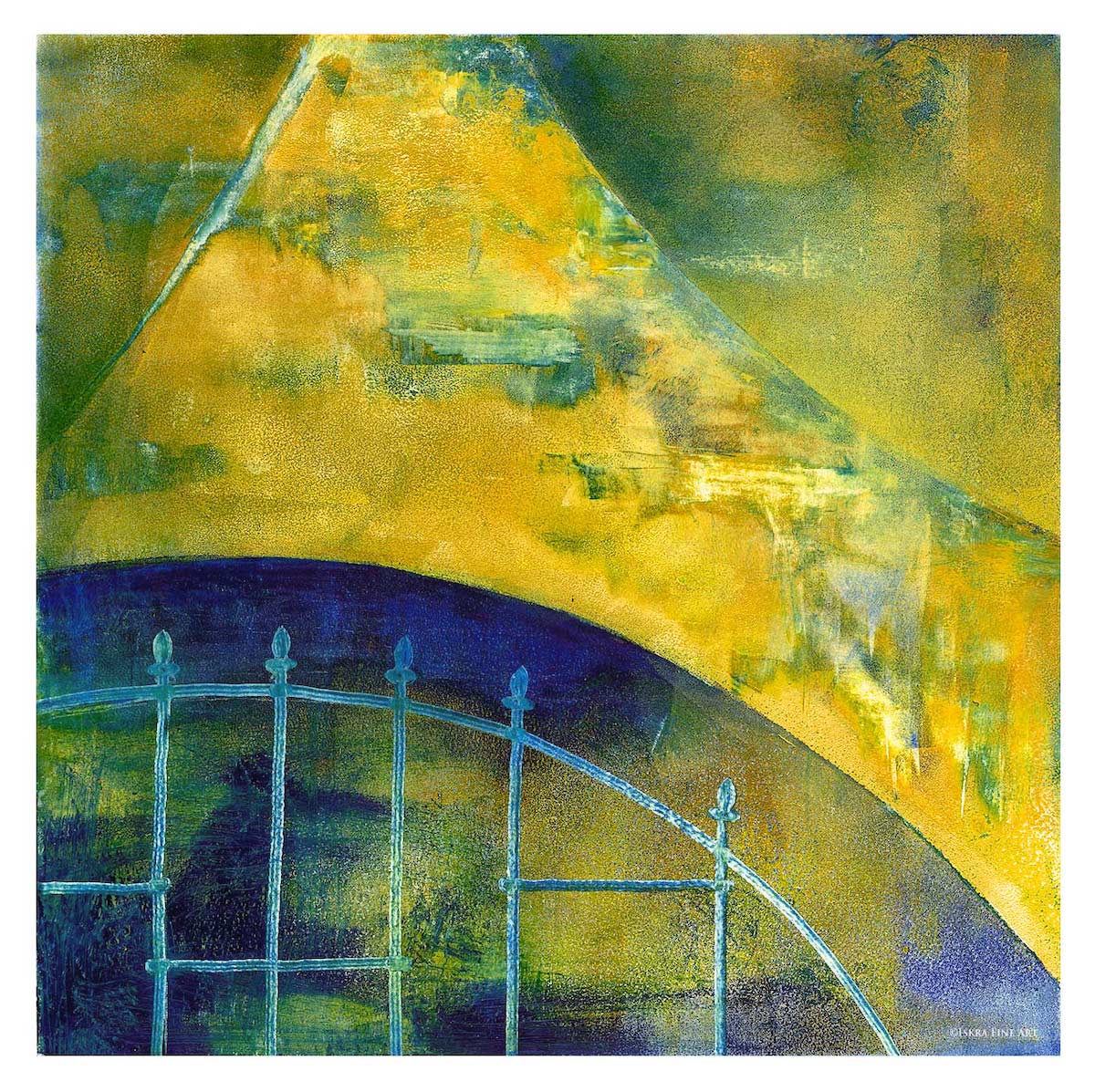

My version of an ex-voto, a contemporary collage built of improvisation, structure, accident and hope:

Seattle is the most atheist and unchurched city in America. I’m sure many here share Junger’s ambivalence about religion, yet wrestle with atheism’s cold comforts when faced with personal erasure. I do not know what the audience at Town Hall came away with. Near death experiences follow a similar choreography, but not all resolve in darkness. Perhaps there were people in the room who walked towards white light and who came back wearing crowns of daisies they can always raise a hand to touch. I would like that very much. If there is a meadow on the other side of the sky I would gladly wander picking daisies, freed of the chains of cause and effect. I would hope in that infrared filtered light, where everything is always soft at the edges and slightly glowy, specific love survived the universal. I would want my mother to still be funny, and only slightly less cranky. What age she would be, wild siren of 26 or 91 yearold grandmother, is another question. For the sake of the news I would hope that as we took a look around, catching sight of those loved and those not yet met, someone took a good picture of the green grass, the flowering tree, and the endless sky, and all of us standing bathed in the light of recognition. I would personally mail it back to earth as proof, address it to some pillow in Saskatchewan or the Midwest, so when that soon to be famous woman woke up at 2 AM she would know that everything was going to be okay.

Leave a Reply