The walker in the city is an innocent and a dreamer. The walker in the city is a tourist, a voyeur, an appropriator and thief. Always with a camera, alert to the capture. And now run home, to flaunt the souvenirs of beautiful decay.

And if the walker has no home but a shopping cart and a space under the Dearborn exit ramp, the walker in the city is a “vagrant,” a word that seems like it should come from the same root as “vacant” but does not.

This person asleep unconscionably at 1 PM under loud traffic is also a thief, stealing a sense of comfort and safety from the other walker, the one with the cellphone held up looking anxiously sideways and sniffing: homelessness doesn’t smell so good.

The support system for the first walker is an entire technopolis devoted to the instant global image stream and the fine distinctions aficionados can make within the pungent hashtags of #ruinporn, #beautifuldecay, and #grime_nation. The support for the second walker is thin, but offers here and there the generosity of climate, a spare dollar, free food or a freestanding and temporarily private toilet.

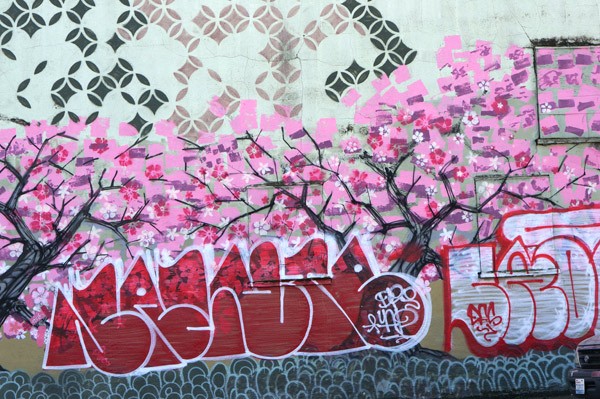

I don’t know if the 13 people sleeping between the Chinese columns on Tuesday requested spray paint embellishment for their living room. Statistics from a study commissioned by the city of Seattle indicate that the taggers at large are predominantly suburban, male, white, 18-35 years old and focused on “fame, rebellion, self-expression and power.” (I would love to have seen the motivational intake interview form….). Unlikely they are thinking of either the wallpaper designs for those who dream in the daytime or the feelings of the muralist who’s cartouche has been deformed by a crudely exploding B.

The emotional effect of graffiti is to double down on alienation. Who owns what? Let’s scream about it. Who owns the view? the conjunction of this and that? The way the sky falls in the corner by the blackberry vine and the man in the white apron comes out to say: We saved the grass for the dogs. Much easier to clean up after them on grass. But I wouldn’t walk over there.

What is appropriation? Doesn’t the person in Armani on his way to a meeting observe the same view as the boy with the spray can? and the guy who just lost his shopping cart? Isn’t the view still a horizon with clouds and a mountain? Maybe subtle colors are a bit brighter under the spraypaint huff-haze, and maybe duller after MD 20/20 than a good martini. All sunsets, they say, were born under the influence, and are the eternal signpost of happy hour.

Who owns happiness, that one dazzling glimpse with the clocktower, the bay, the mountains, and the remnant Beaux Arts hotels framing it all in luminous terra cotta?

I have been away for a long time. Returning to the ID, without illusion, but with memory burned in from years spent on these streets as a student of John Leong I can tell something is off. It’s like the soul of this place collapsed and I can’t put my finger on it. There was always a grace to Chinatown, visible in the layers of history carefully worn and layered, an untranslatable telling of settlement, abandonment and return. It was stoic, and the pain of forced location and relocation showed in its own mute language of architecture and a depth of surface. Every detail of Chinatown declared: this is a place. Now as I walk down Jackson I see a war going on.

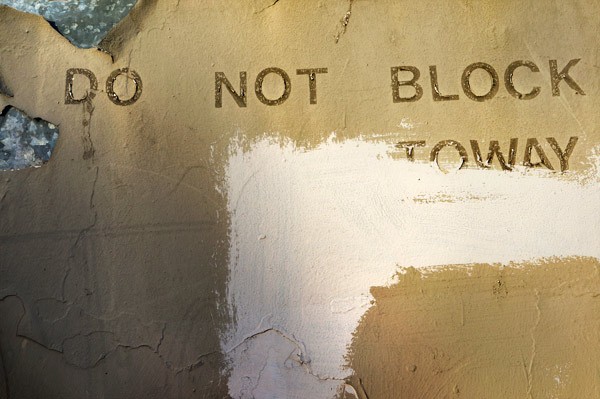

THE BEST WAY: Paint the Entire Wall:

Repaint the entire wall, or paint up to 7 feet high (making a straight line across the top) with a color that matches the wall. This leaves no trace of graffiti and does not draw the attention of the vandals. This method is 10 times more effective than patching.

THE NEXT BEST WAY: Paint in Patches:

When it is not possible to paint the entire wall, use a closely matched color blocked over the graffiti in neat, square shapes. The closer the color match, the more effective it is in preventing further vandalism. Square up your work. Covering over the graffiti in the shape of a square makes the paint-out less noticeable. Clean up drips and spills before moving on to the next site.

–Seattle City Guide to graffiti removal

What you see now is acres of rectangles painted up to 7 feet and a whole lotta inset squares and no drips: the rude face of the war between civic pride, preservation and vandalism. In this exhausting cycle of erasure, insult and re-rasure, a furious energy expends until the buildings seem hollowed out to mere partitions, taped and leaning, and waiting for the next assault.

The influx of medical marijuana shops and massage parlors in Little Saigon, increased homeless encampments and gang activity has not helped matters. The community has yet to recover from the shock last summer of the apparently ‘accidental’ murder of Donnie Chin, and a melancholy hangs in the air.

In the face of this, graffiti’s assault seems even more gratuitous. It shows no distinction between its targets, running heedlessly over hand carved stonework and centuries-old brick, stop signs, storefronts, and meticulous community murals. It’s random drag race path obscures the city beneath it, built of the people living and working and vesting in their community, and not just passing through.

In Seattle’s apologetic conversations of social justice, where the harshest tag is “privilege,” and its lack confers instant righteousness, the current waves of graffiti look suspect. Mostly lacking in any obvious skill, and technically falling more into the category of tagging than graffiti, the markings come across as a form of entitlement imposed by outsiders that degrades the integrity of place and history. You could see it as a reverse mirror image of gentrification. The latter of course is better-funded, and the city does not criminalize it. The ID teeters on the edge of gentrification, it holds its breath, and the City seems to look away. As Thanh Tan points out in her piece in the Seattle Times, there is also shared responsibility, and a cultural resistance in areas like Little Saigon to reaching out to local government and building the processes that will help the community thrive.

As I researched local reporting on development and gentrification in the ID and elsewhere I made a point of reading the comments. The pattern there struck me as not unlike tagging: relentless, dismissive, readily reduced to this exchange:

Something unique/precious/ethnic/historical

is being threatened by:

rich people/white people/brown people/young people/tech people/money itself.

No matter how impassioned the argument for preservation of the former, the comments devolve to some version of this: Before there were Chinese people here there were black people here and before there were black people there were poor Italians and before there were Italians it was Indians so get over it: change happens. What goes missing is any meaningful conversation about value and choice, and the irreplaceability of what is sacrificed to change. The patina and design of old brick and terracotta is not just a gloss for a tourist postcard. Patina is not “just” “surface” it is the record of the lives people lead. The architecture of place is composed of intangibles that are rarely found on the new condo punchlist.

Like the Beaux Arts buildings swathed in scaffolds and gauze I am watching the horizon and holding my breath. Meanwhile, I’m also gathering text messages, and re-coding the street. See more from Text Messages, visual journal notes and sources of inspiration on my Instagram.

In reading about what is going on in the ID, thinking about the pace of change in Seattle and the themes of gentrification and appropriation I came across Arcade’s fascinating issue on Art and Data Culture. This series of articles looks at artists working backwards from data points to create visual representation of personal emotion and place, and it is an extraordinary collection. This piece in particular struck me. I would be very curious to see the idea applied as an emotional mapping of graffiti:

Aleph of Emotions, a project by Singapore-based creative technologist Mithru Vigneshwara, lets us see the world around us through the lens of feelings attached to places. According to writer Jorge Luis Borges, the Aleph is a point in the universe that allows anyone who looks into it to see everything else in the universe with perfect clarity. Vigneshwara uses the Aleph as a metaphor for an infinite archive of emotions. In this work, emotions are derived from geocoded Twitter messages, mapped to their corresponding locations and made accessible through a camera-like device. The user can point the device in any direction, and the viewfinder screen will display a visualization of emotions attached to that place. Aleph of Emotions is compelling in that it links the physical environment to the emotions of others, which we can discover experientially as we move through the world. It contextualizes information that was previously abstract, revealing a hidden truth about the places around us.

Leave a Reply