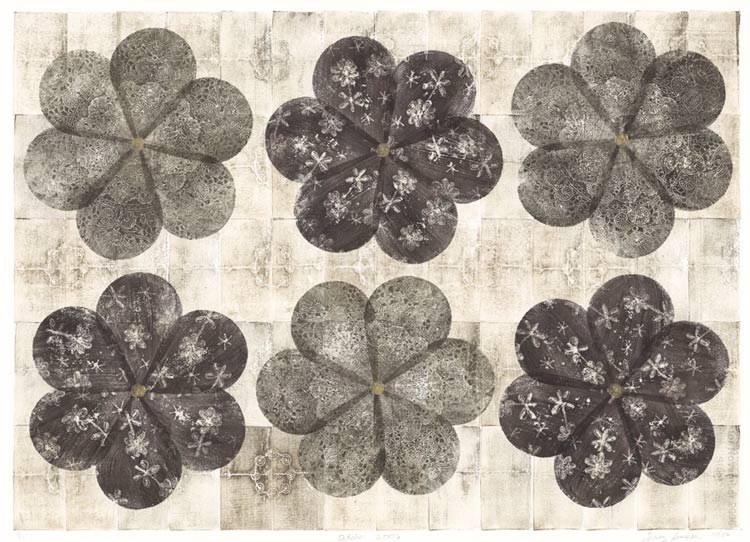

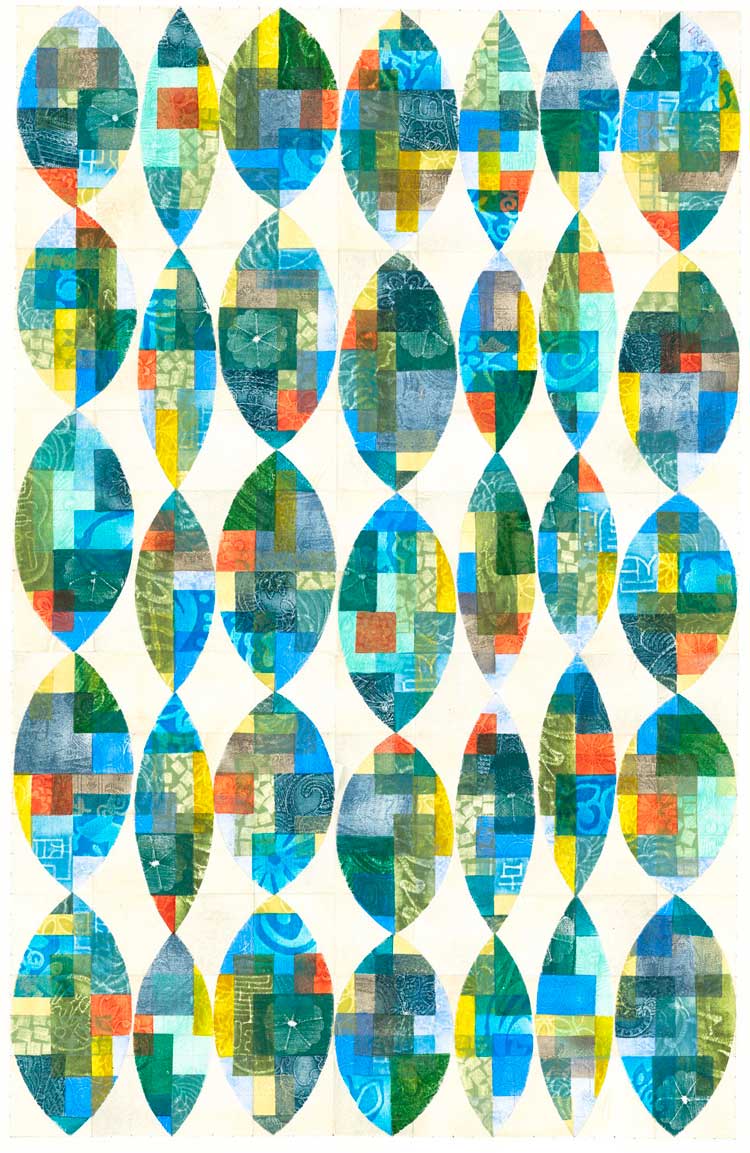

I have been looking for an opportunity to interview Tracy Simpson about her extraordinary potato print “calendars” for quite a while. As a member of the six-person print arts salon Painters Under Pressure, I have watched her work grow and evolve over the course of a decade. Just after opening our current salon exhibit at Phinney Gallery we had the time to sit down at length and talk about her process. What follows is a combination of conversation and correspondence.

From the beginning I have seen connections between your work and that of John Cage. Cage’s work evolved to be the product and process of impersonal systems of chance. This is one way in which he expressed his own sense of spirituality or “zen”: as a path of divorcing his work from the normal sense of self and identification of self with personal preference and personal history. Did this lead to automatism? Coldness? Abstraction only? Hard to say. His music can be aggressively difficult to listen to. But what always comes through to me in his writing, his visual art and his persona is not the automatic or the “no-self,” but a sense of empathy and embrace. There is a kindness in letting go of the personal identification with making art. It can be liberating.

Also, Cage’s work in music is all about time, and not-time, noise and not-noise. In marking time with the structure of a calendar you are indirectly noting its absence and its impending endings. Every month ends on a note, so to speak. The grid structure is not unlike a musical structure, a grid/signature/score with notation. The calendar is scoring the month, even as you physically score the paper. I am interested in how you have chosen a very impersonal structure, the eternal unchanging numbers and grid of the calendar and made it your system. Can you talk about that, about what is impersonal and what is not?

You are right that time is about as impersonal as it gets; time stops for no one, it’s inexorable. And while we may individually have the sense now and again that time is standing still or speeds up for a bit, we know both are illusions or tricks of attention. You are also right that the way time is traditionally organized in terms of seconds, minutes, hours, days, weeks, months, years, and so on, is impersonal. We really don’t get to say hey, I think I’ll step out of time in general or, I’m tired of how we collectively organize time and, really, my way is better so I’ll do that for awhile. For the most part, to exist in the world along with everyone else, we have to surrender to how our particular culture relates to time. So yes, in our culture there is a very set, impersonal structure that developed a long time ago that is partly related to the sun rising and setting and how the moon travels around the planet and partly related to what the collective consciously or unconsciously decided works.

I do like thinking about all that, stepping back and considering what is “natural” in terms of how we as humans relate to time and what we have constructed or imposed for convenience. And what I find even more interesting is how we interact with time. Not only is time the context in which everything happens for us as individuals and for us collectively, but I think there is nothing more personal than how we confront the inevitability of time passing whether it is during a given day or over the uncertain length of a lifetime. What has evolved for me with my art is an ongoing conversation about how I relate to time, its passage, anniversaries, the future, its apparent infinity and my obvious finiteness, how a moment in the morning may color another moment in the afternoon, how a moment in the evening may color my memory of a moment in the morning.

I think that I’ve stayed with the comforting familiarity of the monthly calendar grid because all of this thinking about time and its existential and practical implications would otherwise be overwhelming for me. In the calendar grid I have crisp, clean 90 degree angles that provide a structure or an anchor that keeps me from devolving into a sense of chaos. I also think that dealing with a month at a time and simultaneously the days within a given month is what my mind can cope with. I’ve tried a few times to represent minutes in an hour or all the months in a whole year and I’ve not been able to get any traction or figure out what I want to say about those time spans. I guess I operate best within the mundane, here and now context of days and weeks. Also, within the grid of a month I can zoom in and represent the days and maybe even the minutes within the days in an infinite number of ways while keeping an eye toward how these time intervals seem to fit together for me.

I often want to mark days that are important to me for one reason or another and by restricting myself to working within the impersonal structure of the monthly calendar one of the conventions that I set for myself is dealing with wherever the day or days happen to land in the grid, and thus in the field of the piece. Sometimes this works out well aesthetically and sometimes not so well. I’ve learned over time that since no one else really cares whether there is some sort of abstracted calendar structure underlying a particular piece that I can (and should) emphasize or de-emphasize the day I want to mark depending on how it works for the piece as a whole. I suppose that this is really another aspect of making the process and the work itself more personal and not being a slave to some a priori idea of how I need to relate to the calendar, and thus, to time.

Why did you start working in the calendar format in the first place?

Pure practicality: at the end of 1993 we forgot to get a calendar for 1994 so that February when we couldn’t find one that wasn’t puppies and kittens, I just decided to make one. I didn’t really stop to consider that for it to be functional you need to be able to write on a calendar and see what you have written, so even that first one wasn’t very practical. I hadn’t set out to make some cosmic statement about time. We just needed a calendar. The layers of meaning that I like to ponder got added on (or uncovered) later.

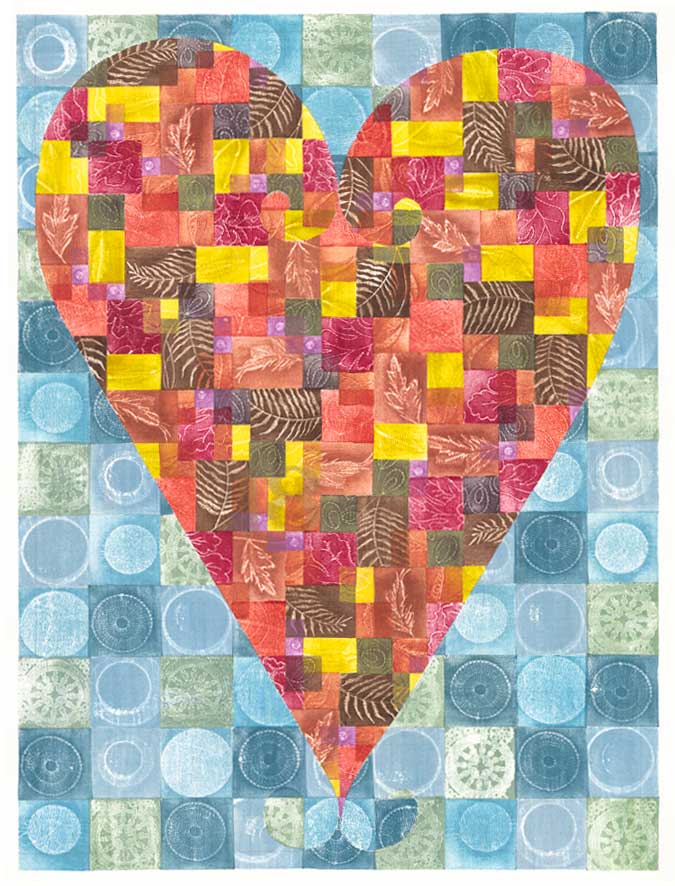

This form gives me a way to express feelings and thoughts and point to certain happenings in my life in an abstracted, veiled sort of way. There are anniversary days that I hold dear and that a few people know about but that the whole world doesn’t necessarily need to know about. I hope that some sense of the importance or weight of those days comes through and even people who have no idea that December 18th, for example, marks an important day for me and my family, will still somehow pick up some of the emotion around it. And if they don’t, they don’t. Either way, I have a way of marking situations that have shaped my life. Moving back and forth between considering the shape of a month, where a given day or days falls spatially in the month, and how I want to represent the individual days within the structure helps me see that time and my relationship to it is layered and fluid rather than one-dimensional and static.

How has the calendar evolved from the traditional format into what it is now, almost completely abstract?

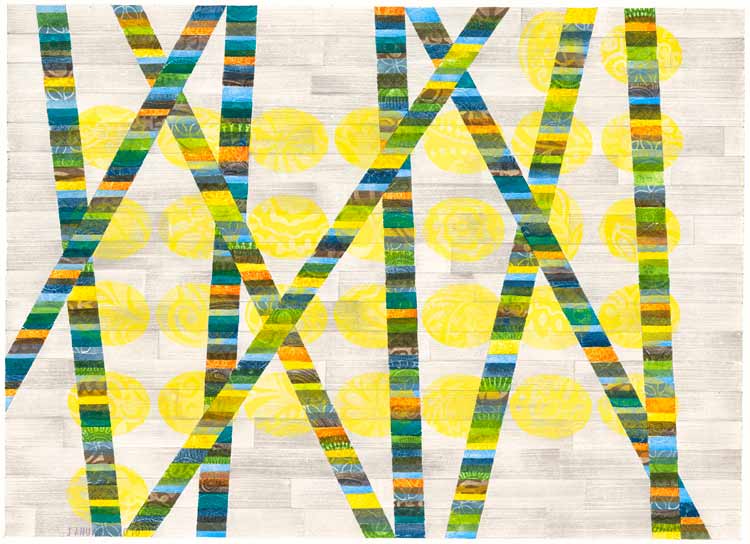

When I first started it felt really important to me that everyone else could tell that the various pieces were literal calendars. There was something comforting about having a readily accessible form that I could understand and relate to and that I thought others could as well. I really liked finding new sets of number stamps and setting out all the numbers in their proper places and at some level I’m still drawn to the literalness of it and the idea that something so ordinary as a calendar might be rendered as art. Over time, I found that I didn’t need to make quite so much of a literal statement. I can work more surreptitiously with the structure of a calendar month and it doesn’t have to be the obvious organizing theme of the piece anymore — even though I’m often still doing something particular or specific within a given month. Lately, I’ve even been turning some pieces on their sides and completely losing the original calendar. I don’t think I’m really done, though, with representing calendar months literally – there’s more to do with that, just not sure what yet.

Do you see your work as art or craft and how do those two ideas work or not work for you in placing what you do in the world?

I like to think of my work as craft inspired art. I don’t see there being some sort of magic line where there is craft on one side and art (fine art?) on the other. My not at all scholarly take is that art is fundamentally based on craft, that craft (at least loosely defined) probably came first and became increasingly artful and eventually spun off into new expressions that didn’t have practical, useful functions but that still hold echoes of craft.

Until pretty recently it seemed like there was quite a bias against things crafty or craft-like, at least on the part of fine arts people. Maybe there still is. I like being something of an outsider and not getting caught up with art world schisms. Getting back to craft and bias, my sense is that there is a lot more appreciation in recent years of craft and things that are handmade. I remember after 9/11 it seemed like everyone was learning how to knit or do something with their hands, something concrete and tangible that could be used and maybe given away. It’s really nice that this has seemed to continue, that there is a value placed on the handmade and not just on the mass produced.

What are the connections in your work with quilting and collage?

When I was in my 20’s I tried quilting a couple of times, but it took too much patience and I couldn’t get good at it fast enough. So I have found other ways to achieve quilt-like effects with my printing. The layering that I can do with printing is a wonderful advantage of this method that can’t really be achieved in quilting unless one is using sheer organza or similar transparent fabrics.

The first time I used fabric I was making a piece to commemorate when my family and I joined our church. I was very set on depicting the graphical quality of the bird shaped cut-outs in the glass brick windows in our sanctuary and so I planned to carve the two different bird shapes and represent each day with a bird silhouette over a contrasting solid (the month was December 2005). But I also wanted to get some reference to Jesus in there and decided that if I could get the print to convey a loosely woven fabric, it would sort of connect with his shroud. The month of December and celebrating Christmas always reminds me of the crucifixion later in the cycle, which reminds me of the shroud. There are also the swaddling clothes that baby Jesus is purported to have been bound up in, which would have been important fabric at the other end of his life.

I started experimenting with fabrics and found that the loose weave of an old linen shirt of mine that was falling apart did quite nicely; it had some character and nubbiness but not enough that it was dominating. If one is standing up close to the print the warp and weft of the fabric is apparent in the paint and when one is standing back from it the fabric quality recedes but still softens the silhouettes and allows more of the paint underneath to come through.

Why potatoes? Did you start with other printmaking methods?

The one art class I took in college was a block printing class and we used a bunch of different things to create the images for transfer, including potatoes. I’ve always been pretty low tech so the potato version of block printing appealed to me most. I have tried to use other methods (monotype with a press) and means (lino, wood) but for some reason I just find potatoes to work best for me. I work at our dining room table and keep a bag of potato pieces in the refrigerator. The pieces have to be trimmed to get squared up and to have a new face that will take the paint properly, but I can use the pieces over and over again for quite some time if I’m not carving them. Any carved pieces have to be used the same day because the potato deteriorates enough in a few hours that the integrity of the carving is lost really soon. And in case anyone is curious, russet potatoes work the best. I think that their starch and moisture content somehow interacts well with acrylic paint, it is possible to get an incredibly smooth printing surface, and they are sturdy enough to hold up to a lot of very firm pressing and manipulation. I have used sweet potatoes when I’ve needed a really large piece but it’s hard to get the printing surface smooth enough and they tend to leak orange (and they rot really fast).

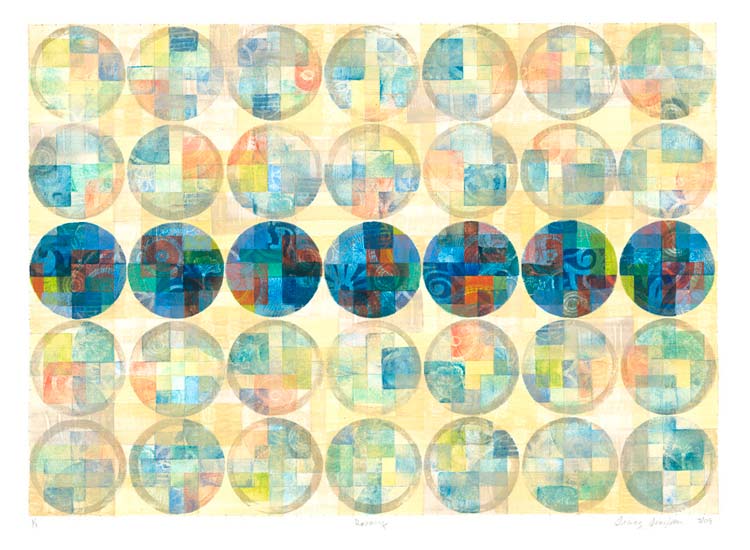

The printing itself involves cutting a piece of potato to whatever size I want to work with; 1.5” by 2” or ½” by 1” or whatever. I use a small, thin metal ruler that has inches marked on both sides so that I can cut square and I use a really sharp kitchen knife for the actual cutting. It’s really important that the printing surface is perfectly smooth. After being cut, the printing surface gets blotted on paper towels so that it isn’t wet. Then I use a paintbrush to apply the acrylic paint, press the painted face of the potato to a section of fabric with some sort of texture, and then apply the potato face to the paper. The potato and paint essentially serve to transfer the image from the fabric to the paper. Depending on the size and intricacy of a piece, I’ll then repeat this process between 200 and 500 times until it’s done.

How do you want your work to affect people? What is the vision that you are sharing?

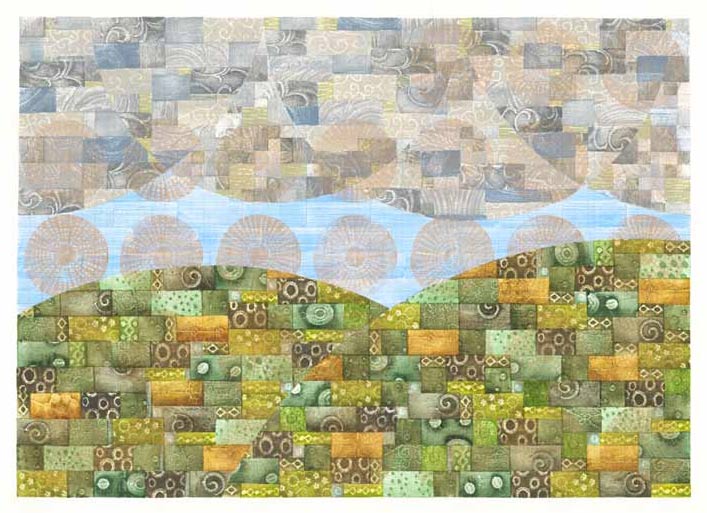

Stepping back from all the layers of personal meaning that are embedded in various non-literal and inaccessible ways, what I want to convey with my art is the fundamental tension between order and chaos, the tension we feel when we have to confront what we can and cannot control.

So much of what we can’t control has to do with time and some of what we can control is what we do within our various time intervals. It’s a paradox that the grid representing calendar months conveys a sense of order even though time is so fundamentally what we can’t control. From several paces back it’s usually apparent in my pieces that there is a structure that is linear and at least somewhat predictable even if the calendar underlying the grid doesn’t translate as such. From a distance I think the control and order is what is most apparent, and this is how things may seem in most of our lives.

There’s a line in an Iron and Wine song: “everything looks perfect from far away.” I’m not saying that my work looks perfect from far away, but rather that it may get at the idea that when we are far away from something we can’t see the chaotic imperfections and the strange collisions and juxtapositions, we can’t see the details. My hope with my art, is that it will work at both the several steps away distance or even the across the room distance, and up close.

How does your own spiritual/religious practice involve your art? Some artwork is meant to encourage a state of contemplation in the viewer, some is made to be a contemplative process on the part of the artist. Sometimes a contemplative effect in the finished piece may be hair raising and stressful in the making. How does the deliberation and slowness of your way of working reflect contemplative practice, if it does?

Often the making of a piece of art is a way for me to shift from my usual highly verbal and analytical way of relating to the world to a way of being that is more contemplative and quiet. Although there is always a plan and a specific vision guiding me, once that verbally mediated framework is set, there is a lot of freedom to play and experiment and much of that is driven by an intuitive, non-verbal sense of what needs to go where. In a way, this parallels how I experience spirit and the divine; there is a basic framework provided by my faith community that is enriched by my meditation practice, and I find that it is made real and comes alive in the millions of little moment-to-moment embroidered details that flesh out my life, not unlike the hundreds of repeated geometric shapes with which I fill my calendar grids.

At the level of process, I often find that the act of printmaking allows me access to a sort of liminal space where I am freer because of the clear guidelines. Just as there are infinite ways to live out a moral, loving life, there are infinite ways to express one’s relationship to time and mortality even within a fairly predictable, and for many of us, necessary grid. And really, for me, my spirituality and my art are both expressions of my core need to make peace with mortality. The main practice in rising to the challenge of this is that of staying present and focused on what is in front of me. That idea of monkey mind that meditation teachers impress upon their students is relevant here. When I get a narrative going that involves worrying about whether others will like whatever I’m doing or if a piece “works” or convincing myself that a piece is strong, then my attention flags and I tend to make mistakes. Usually they are small and I can just use them to remind me to come back. Amish quilters would intentionally put a mistake in their quilts “because only God is perfect.” I don’t have to put intentional mistakes in since they find their way in on their own, but I do comfort myself with the idea that they are my Amish mistakes.

I have felt for a long time that I am one of those people who has instant karma; if I am thoughtless or speak poorly of someone or engage in some sort of transgression I almost invariably immediately stub my toe or get a splinter or some such small painful wake up call. Same thing in art making. The universe seems to continually call me back to the present moment and I feel like one of the ways I’m at my best in these moments is when I am quietly placing bits of color next to and over each other within a simple set of lines.

All images © Tracy Simpson. You can see her work at her website and at the current exhibit with Painters Under Pressure, from April 3- May 1, 2013 at Phinney Gallery.

Ruth Hesse says

Yay, yay, yay, I have wanted someone to write about Tracy and her process for so long. Great interview, Iskra, and I love the photos from Tracy’s studio. Several of the prints in this piece were new to me, so thank you for sharing them. Tracy’s beautiful spirit shines through in this interview.

steve says

Bravo! Excellent interview – kudos to you both! I think the link between Tracy’s work and that of John Cage is worthy of comparison. Tracy’s concept of a rigid controlled environment, or time grid, acting as a support for all the daily choices, experiments and events we put into our time here is a very freeing one. Instead of a worry that our time is not always being used effectively as it marches inexorably on, the framework can be used to step back, see our lives as a whole, marked by events and experiences, past, present and future. Very meditative. I find Tracy’s work and words to be unlike John Cage in that she is never aggressively difficult to listen to. She is without a doubt empathetic and embracing and her work, liberating.

del webber says

What a wonderful and revealing conversation. Most of the artists and crafts people I know will see a bit of themselves and feel a warm glow. Tracy’s work and process express the quintessential artist’s spirit: concept to invention.

David Owen Hastings says

What a great conversation! I love it when artists talk to each other. It builds bridges, and builds understanding. I especially enjoyed reading how Tracy Simpson thinks about her work. Very special indeed.

Jessie Attri says

Tracy, there is so much to think about! Why do I like this? What are you trying to do? How can so many kinds of painting appeal to me?