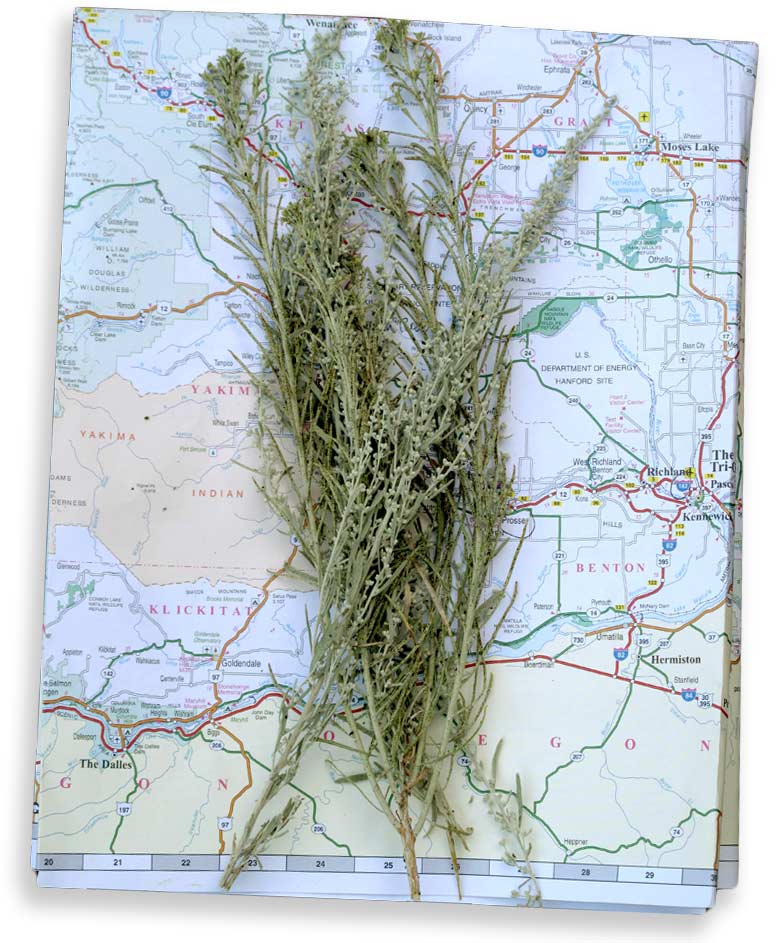

Weeks after returning from Eastern Washington, I can’t seem to put the map away. From the corner of my eye I see the blue of the rivers and the lakes and the pale butter of desert and wheat. The whole map seems cast in the blue of the sky. It keeps me on the road even as I stand in my kitchen looking at weather the color of concrete. I read the names of the towns and put them together, knowing I would believe these people were real if I read them in a story: Clayton Ford, Lamona St. John, Gilmer Packwood, Randle Bingen, or just plain Quincy, with no last name. I want to have a cousin named Mayfield, and I want to marry a man named Dusty, which lines up along the road to Othello right next to Hay. To look at the map, to be in the map, they infuse each other – the blue sky the same color as these meandering backroads. The names of these places are equal parts dirt and aspiration. Yes to the beat up range horse and the saddle whose rosette tooling has worn flat from years of use, and yes to the Spokane carousel whose horses bloom with gilded chinoiserie.

Weeks after returning from Eastern Washington, I can’t seem to put the map away. From the corner of my eye I see the blue of the rivers and the lakes and the pale butter of desert and wheat. The whole map seems cast in the blue of the sky. It keeps me on the road even as I stand in my kitchen looking at weather the color of concrete. I read the names of the towns and put them together, knowing I would believe these people were real if I read them in a story: Clayton Ford, Lamona St. John, Gilmer Packwood, Randle Bingen, or just plain Quincy, with no last name. I want to have a cousin named Mayfield, and I want to marry a man named Dusty, which lines up along the road to Othello right next to Hay. To look at the map, to be in the map, they infuse each other – the blue sky the same color as these meandering backroads. The names of these places are equal parts dirt and aspiration. Yes to the beat up range horse and the saddle whose rosette tooling has worn flat from years of use, and yes to the Spokane carousel whose horses bloom with gilded chinoiserie.

Here in The West, in the upper left-hand corner formerly known as The Oregon Territories, (and before that as the land of the Nez Pierce, the Quinault and the Yakima Nations), we are divided by mountains. The usual associations of the compass don’t hold; The “East” is not know for its Buddhists and pagans and barefoot Occupiers but for small towns with even smaller churches with firmly held conservative beliefs. The West curls its lip at the East and mocks its Bible-quoting politicians and lack of tender regard for restoring the gray wolf. The East would prefer not to sponsor seawalls and fancy underground freeways and weddings in which both the bride and the groom are named Meg. And yet for all its smug urban insularity, people of the West regard the East with nostalgia and they carry a certain ache for its rural beauty. Out there is the land. No matter how thick the condominiums or how constipating the traffic or how high the price of a double latte vente with vanilla on the west side, the land is out there just over the pass saying: we have space and sky here for you. It’s saved for you and in the bank: beauty.

Every few years I make the pilgrimage across the Cascade mountains, to see if that space is still there or if I imagined it. This August I went with two artist friends to stay on a farm outside the farming town of Pomeroy and look after a herd of goats. It was delicious to be with companions who live to stop and to look. We packed a week of lunch, and checked our brakes for the long steep slope down the other side of the mountains.

After a bit, beyond the too-big fruit stand that is now the only fruit stand, in the town of Thorp whose name seems too short and where the massive marquee offers “Antiques | Fruit” which just makes us think of raisins; after that bleak stretch where we think we’re not anywhere at all, we do reach The Road. Here finally is the ribbon of hills. The folding and unfolding waves of gold and green pivoting into creekbeads and scree and broken down things. Shimmering asphalt, blazing hairpins, the river, the barges, the Falls. White butterflies in pine trees. And a sudden leap into science fiction. When did the land become a wind factory? I turned my back and the Germans came and put these white giants, these three-armed industrial starfish on every horizon. What would Ray Bradbury think? Would he lie down beneath them in their protective mote of gravel and toast them with a glass of dandelion wine?

Each windmill earns a farmer $10 thousand dollars a year. Each windmill powers 350 houses. Put that up against an idea,– a relic of an idea — of “landscape” or “natural beauty.” You’ll lose. And so we go farther east, to where the migration hasn’t taken hold, practicality and beauty are in harmony, and the highest best use of land is wheat and peas and these are just coincidentally lovely.

We settle in with the goats.

It is tempting to name the goats. Certain ones, like the brown baby who’s mother won’t nurse her. Or the goat who belongs on TV, or the calm white ones who always sit down as a pair. But these goats live on a farm, not a zoo, and so they are not long for this world and all affections are temporary. In the evening their bells ring for compline service as they gather without speaking, kneeling in the dusk. In the morning they gather at the fence and bray their impatience with the late dreaming of humans. The dog whirls, nervous with hunger, not for the food we eat but for our touch. She nuzzles and prods and shimmies her way into every moment with a wet nose and an eager tongue until we shoo her away in exasperation.

In the afternoon the flyswatter seems like one of the great inventions of all time. I turn the rocking chair in the other direction and contemplate a Shaker life. I want simple thoughts, evenly-spaced.

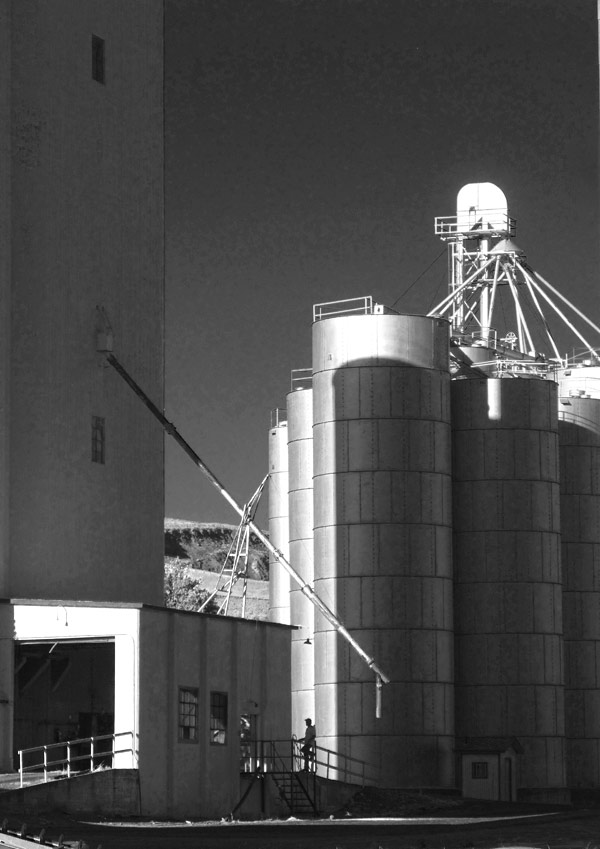

We go into town. And on the way I fall in love with the Pomeroy grain elevator.

Each time I lift my camera I cannot help but think of Charles Sheeler. I have always looked at his work with awe. His drawings of architectural structures, particularly the grain elevators and rural structures of Bucks County set a standard of abstracted, cool perfection. And yet. I find myself wondering as I look at these very real and very useful towers, as the trucks bellow past me and I wipe the dust from my viewfinder: is abstraction merely a luxury? Is there something decadent about this love of form?

This photograph has a blue sky, and the man is wearing pale clothes that blend into the color of the towers. If I were Sheeler would I erase the man? He stepped out of the frame ten seconds after I shot this. If this man was clearly working he might suggest the idea of The Laborer. As it is, he is now only a Figure, and only the faint suggestion of a baseball hat locates him in a certain time of human evolution. He could be a Tourist.

Sheeler once said, “My paintings have nothing to do with history or the record–it’s purely my response to intrinsic realities of forms and environment.” I love how William Carlos Williams put it: [the artist] “is the watcher and surveyor of that world where the past is always occurring contemporaneously and the present always dead needing a miracle of resuscitation to revive it.”

You can see a comprehensive set of Sheeler’s work here, including his eloquent paintings and photographs of Bucks County barns. He supported himself for many years as an architectural photographer, capturing the soul of geometry. I feel him behind my eyes everywhere I look. I don’t think he would apologize for his lack of socialist realism or Grant Wood twists of melodrama and loss. Sheeler was less nostalgic than simply in the moment, and he could not resist his precise and radiant vision of what was exactly in front of him. I am struggling as I look at the New. I want horizon lines unbroken, or broken by the broken–I crave the picturesque. The rotting windmill, the decaying barn, the useless, as though only when rendered without purpose do these things become beautiful. It is time to drive up into the Blue Mountains to a real farm, to visit Mary’s place in Peola.

Paint What You Know

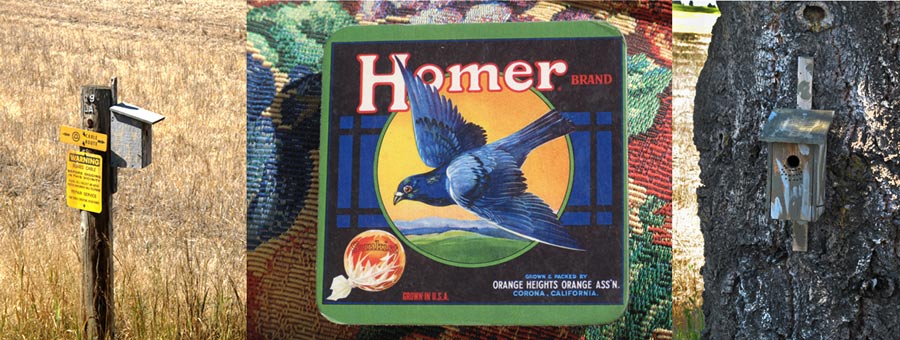

On the way to Peola we pass dozens of bluebird houses. It turns out this is not only the Lewis and Clark trail, but the Bluebird of Happiness preservation trail. Tom Scribner and his son put the houses up all along the roads of the Blue Mountains, part of a campaign throughout the country to keep these totemic birds alive in the face of loss of habitat. They like fences. And trees. Two things increasingly hard to come by.

The people of Pomeroy came out here in covered wagons. In the hills you can still see the traces of travois from the people who were here first. Mary’s farm is over a hundred years old. Her sons learned everything they might need to know from fixing the combine, and have gone on, as have many young people in this area, to careers in technology and computer science. Now there is talk of starting a farm museum, where the next generation can learn to make rope, and fix things, a rural version of Shopclass as Soulcraft.

Mary paints her horses. The fence. The Vesper Sparrow. Then the ocean. The Inland Empire is an inland of sea. If you have seen wind running over the wheat in late afternoon you know what a wave looks like and if you have studied a horse bucking with its white tail spread against clouds you know surf and how things rise and crash. Would you show it? Do I have to put a price on it? Well, you could ask a whole lot. I don’t want to sell it, this is to remind me of where I live. I don’t know if I could ever paint another.

Her daughters paint without asking. It seems natural that roses climb on skulls, that wolves live in the house, eye-level with men in cowboy hats.

You can see what Mary is up to and the work of The Blue Mountain Artisans’ Guild if you visit Pomeroy sometime. They have a new storefront gallery on the main street. And do stop by the Holy Rosary Church, which has been lovingly restored by members of the church parish and the Guild, under the expert guidance of skilled muralist and painter Jennifer Carrasco.

Steptoe Butte

The man is in his late seventies, silver haired and leathered. His open shirt flaps white in the wind; the six o’clock sun behind him lights him up like a sail. He paces and shouts into his phone. Broadcast from the tailgate of his station wagon, we know everything that he did not bring with him on his trip, starting with food and silverware. I don’t even have a jackknife. Hell I didn’t bring cold cuts no. I didn’t bring a toothbrush. The campgrounds are full. I can stay here for fifteen minutes without paying. Forgot my boots.

His one-sided conversation drifts far in this clear air. We are sitting on the other side of the hilltop listening for the space when the wind can gather, the silence can settle into us: That one curve of the field half a mile below, the way the pines give way to poplars, both casting different shadows into the secretive valley between two hills. The colors, flat ochre bleeding into transparent gold and the thick viridian of the valley. The man’s voice shifts back and forth, jocular, then angry, then beseeching. I turn and look at him. Posed beneath the massive cell towers with his phone to his ear, he almost blends into the grid structure. He shimmers like the towers, his white hair is a small cloud against the implacably blue sky. He has come all the way up to the highest spot in south eastern Washington to tell us about his loneliness.

Thirty feet below him, at a bright white guardrail, a dozen photography students aim their cameras at the chosen Best Shot, and the click of their shutters mixes with the chit chit of the occasional swallow. You always say that. Always, yeah. I didn’t come all the way up here to argue. Why would I bring a sleeping bag.

I think of hotels and motels, and how sometimes you land in one where they supply you with a wrench to turn the hot water on and the cold is just a hole in the sink. The curtains at the bedroom window smell of nicotine and the floor comes up under your feet. But you’re with someone and so it doesn’t matter.

I’ve been visiting Steptoe Butte for many years. It’s a place to go to fill yourself with space, to enlarge your view.

Evening

The land has animal presence, but it breathes on its own and asks for nothing. The hills slope down to the road like the flanks of great beasts, tawny with wheat-colored fur. I feel this presence most strongly at night, as though the hills, still warm from sun, press against my side as I sleep. On our fourth evening I am suddenly restless with the need to be alone and to walk. Sunset here takes a long time, and the sky is translucent and vibrant with color. It’s like walking through a bottle of very fine wine. I close the gate behind me and cross the road into the fields. Beneath my feet the dirt is soft and cool. I read the tires of tractors and the small arrowheads of birds, and then I notice something else: a narrow continuous ribbon with regularly placed diamonds. It’s thin like a ten-speed bicycle wheel, yet when it reaches the fields the grass shows no entry. They have warned us of rattlesnakes, and I don’t know what kind these are. My senses quicken. I am paying attention now.

As I approach the top of the hill the light begins to dim and the stones ahead could be birds. I pause to see if they move, and some of them do. One takes flight and the song of a meadowlark rises against the sky. I look down, carefully, wondering if snakes sleep at night. In a few more steps I reach the top of the hill where the road ends in a combine and stubble. To the west the sky’s deepening indigo ends in a pink line. The sun is gone.

I turn around, face to face with the rising moon. It is full, and brilliantly gold. There is a faint wind, but it is soundless. For a long time I don’t think I breathe. I stand until the moon has risen completely and the orange color begins to fade from the grass. I realize that I am cold, that it is getting dark, that I don’t know if snakes sleep. As I start down the hill I shiver and I start to sing a song: Down in the valley, the valley so low. Just as I start the second stanza a piercing shriek cuts the air and a white owl sweeps ten feet above me. Startled, I pull my sweatshirt up above my head, as another owl heads directly at me from the opposite direction. Write me a letter, send it by mail…. The two of them criss-cross above me, lower with each pass, and I call out involuntarily, “Not prey!”

I can see the farmhouse below me now, the lights from the reading lamps warm in the windows. The howl I hear is not a coyote but Mable, dear needy bustling in-the-way love-hungry dog as she bounds through the gate. She runs across the road and up the path and greets me with unadulterated animal affection. I reach down and pet her all over and sing to her low in her ears. Angels in heaven know I love yoooo. Know I love you dear know I love you. (You, baby are a girl’s best friend.)

The owls have vanished. To the gentle sound of goat bells I open the gate and step into the warmth of lamplight and tea .

All photographs and text © Iskra Johnson

Laura says

Beautiful Isk.

Jocelyn Curry says

Thoroughly beautiful, lyrical, and loving. Fabulous photographs, through and through. A labor of love!

Parker Lindner says

Thanks for returning these glorious images to my mind’s eye. Eastern Washington is a gem.

Jon Taylor says

Iskra – You have taken us to the other side in words, poetry and pictures to show your view of a land of sparseness, power and riches for the soul. I covet the Oregon Coast for real world meditation. For me Eastern Washington and Oregon have the same great strength and calmness with a dry twist.

Thanks for being an artist/photographer/lover of land, inhabitants, architecture and light.