October in the Pacific Northwest is a moody season. The rains have come, and the fugue state of grayness that leads to indoors brooding requires acts of increasing will to resist. Sunday I felt myself on the cusp of succumbing to what the Buddhists aptly call The Third Hindrance of Sloth and Torpor. Seattle’s caffeine economy is built on what may seem like indulgence: yet consumption of caffeine is actually the first step in Spiritual Effort. I dutifully poured three cups of tea and purified my mind.

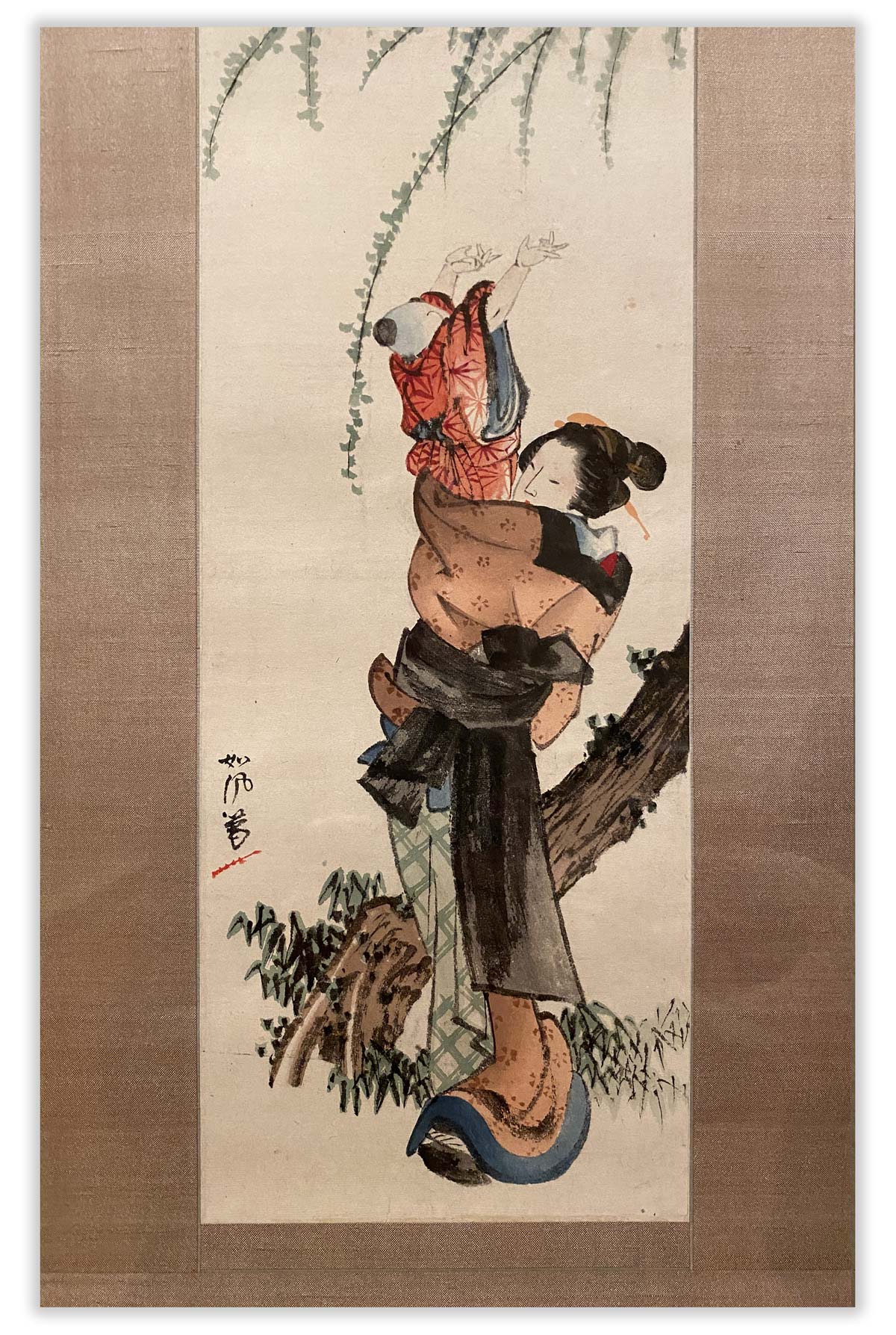

Once prodded out the door and feeling clouds on my face I came back to life. The innumerable grays of our skies offer a perfect foil for color, and walking through the blur of crimsons, burnt gold and lichens filled me with calm elation. Still facing East after seeing SAM’s Hokusai, I prolonged the spell of the exhibit with a visit to the Japanese Garden. As I walked through the Japanese garden each tree and stone seemed redrawn in ink in isometric perspective, and I half expected my viewfinder to appear with parallelograms drawn across the glass.

When we are barraged daily with thousands of images seen online it is easy to forget the power of an image seen literally on screen, as in a painting on a folding screen of silk, from hundreds of years ago, holding history present with the physicality of thread. My favorite images from the Hokusai prints showed the ghost seepage of aged rice paste and seams where sheets of paper or silk overlapped. Seen close I noticed embossments of cloud forms I had never caught in reproductions, and this evidence of the physical making impressed memory on me as a bodily thing, amplifying the exhibit’s power.

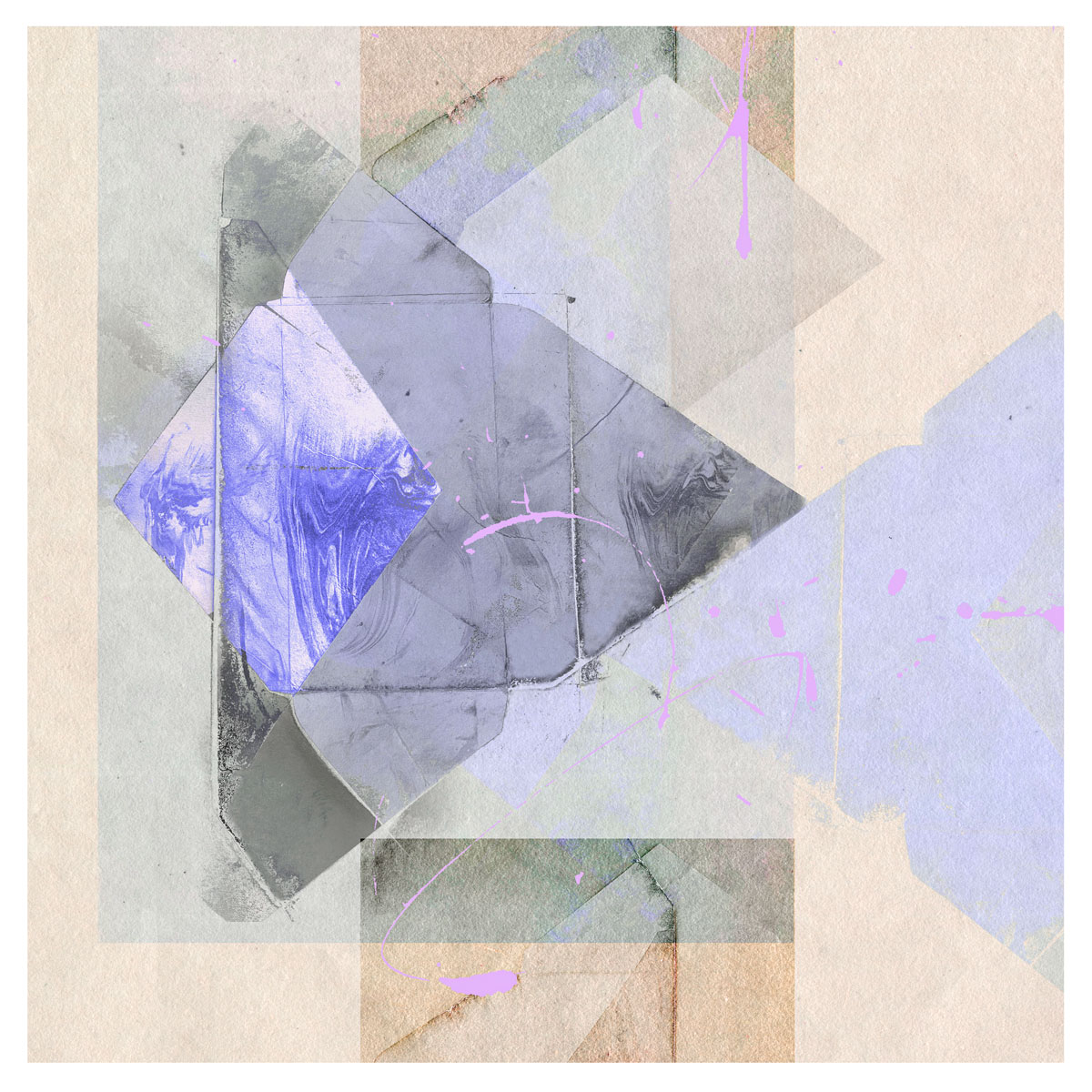

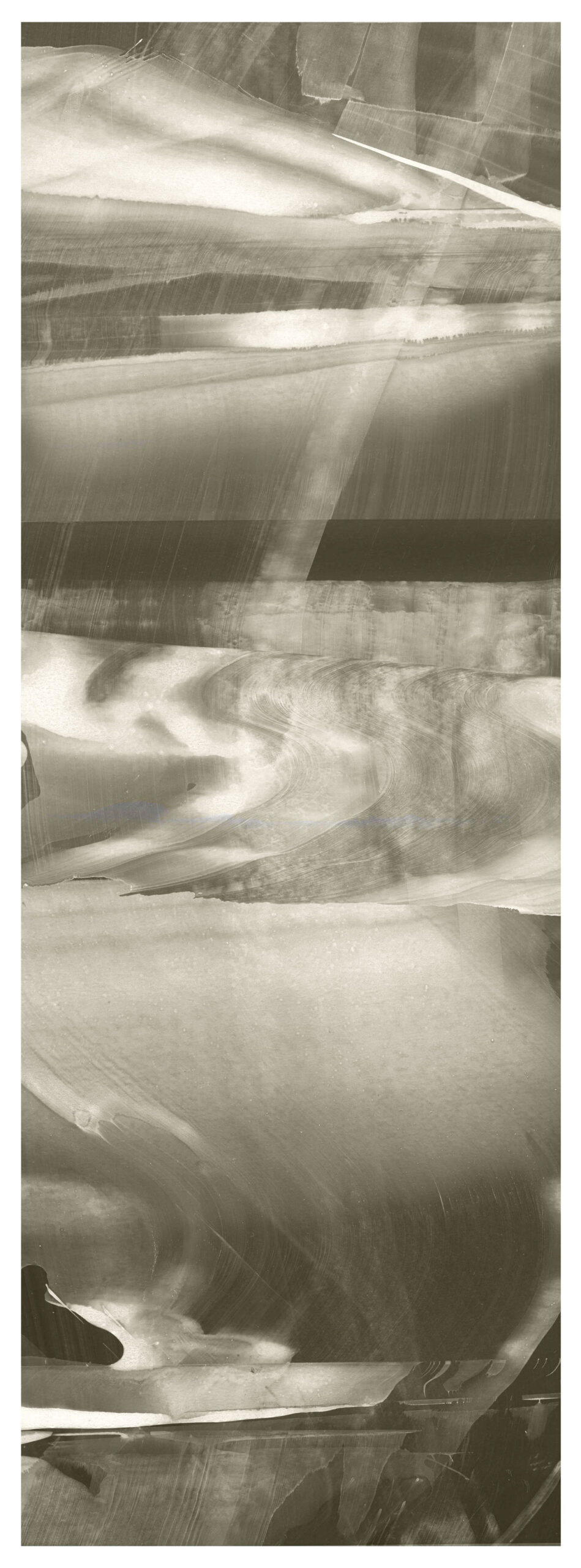

I often work on what seem like opposite directions at once. It is a counter-intuitive habit that impales me with uncertainty, yet it pushes me beyond preconceptions. To prepare for a month-long trip to Britain I am studying the history of British landscape painting under the guidance of author and artist Christopher Neve. I just received his book, Unquiet Landscape and cannot wait to read chapters with titles like “Melancholy and the Limestone Landscape” or “Seeing Becomes Feeling.” Meanwhile I am at work on an abstract print series based on calligraphy and kimonos, for which I am reading Sei Shōnagon’s Pillow Book. This journal of a woman courtier and poet of Japan between 970-1020 is perhaps the first example of “collage writing” in historical record. She established the unapologetic non sequiter as a viable form of literary composition, and I am enthralled. Her “list” prose poems are legendary, and I find myself wanting to chase after her flower-strewn carriage with my own pages as she dashes through rain to hear the cuckoos sing.

44.Things That Cannot Be Compared

Summer and winter. Night and day. Rain and sunshine. Youth and age. A person’s laughter and his anger. Black and white. Love and hatred. The little indigo plant and the great philodendron. Rain and mist.

When one has stopped loving somebody, one feels that he has become someone else, even though he is still the same person.

In a garden full of evergreens the crows are all asleep. Then, towards the middle of the night, the crows in one of the trees suddenly wake up in a great flurry and start flapping about. Their unrest spreads to the other trees, and soon all the birds have been startled from their sleep and are cawing in alarm. How different from the same crows in daytime!

True, one cannot compare, one can only give in to simultaneity as the pages turn and the mind leaps. One minute I am deep in Heian Japan, and the next standing on the River Wye, 1770 at “the birth of the picturesque.” Long ago on a hike in the Lake District I thought I would make a casual stop at Beatrix Potter’s house. To my dismay I could barely squeeze inside. Five busloads of Japanese tourists filled the estate to brimming and the line to buy a bronze rabbit went round the block. The affinity of these two island nations runs deep.

Last night I attended a poetry slam, and because of The Pillow Book peeking out of my purse I learned that my table companion was a Butoh dancer who lived for decades in Asia. We began a discussion about appropriation, belonging and the confounding and ever-shifting rules of today’s cultural environment. Who is allowed to look at what? Who is allowed to wear what and where? What does it mean when a white woman wearing whiteface performs Butoh? Why do Japanese tourists love Beatrix Potter? What if Peter Rabbit married Hello Kitty. . .?

The older a woman is, the more subdued the colours she must wear. Therefore you’d not see a mature woman in something like bright red. One way to produce a more subdued tone for a mature woman’s kimono is to dye the textile a bright colour, then re-dye it in a light, mouse-grey tone, to subdue the brightness; this is rather cutely known as ‘through mouse’, so a subdued pink would be pink through mouse.

This line of thought led me to a list of what the internet thinks colors mean in Japanese art (see above) and to considering things a non-Japanese artist could get wrong about kimonos. This would inhibit me if I hadn’t spent mornings at a Baskin and Robbins in Tokyo in 1980 watching a Japanese motorcycle gang eating jello for breakfast– jello with whipped cream topped by neon apples (imported from Washington State) carved into roosters. Within hours of landing in Tokyo my friends took me to a festival at a Shinto temple. There, to my amazement, I was urged to try the ring toss, and see if I could get it to lasso a Pink Pearl eraser or a bottle of Jack Daniels. As I tried in vain to win the eraser a canopy of Mickey Mouse masks leered at me from the rafters. I believe Japan may have invented intersectionality, and in the appropriation contest they win hands down.

On that trip I also had a lunch at a traditional Japanese home with friends of my hosts. An elegant older woman dressed in a formal kimono peppered me with questions, sharing that during the war she had worked in munitions factories assembling bombs. For a year afterwards she mailed me collages she made from Western magazines cut up and glued to calendars. There was no signature, no letter, just the return address to identify the sender, and to let me know the war was over and we could be each others’ muse.

Told to paint red maple leaves floating on the Tatsuta River, Hokusai supposedly drew a few blue lines on a long sheet of paper and then, dipping the feet of a chicken in red paint, chased it across the scroll, making the bird’s red footprints his maple leaves. –Carnegie Museums

You can see the newest work that has come from my studies in the Minimalist Modern Portfolio. Drop me a note and let me know what you think!

Leave a Reply