“…the camera does more than just see the world; it is also touched by the world. Light bounces off an object or a body and into the camera activating a light-sensitive emulsion and creating an image.”–Geoffrey Batchen

“touch is the most demystifying of all senses, unlike sight, which is the most magical.” — Roland Barthe, Camera Lucida

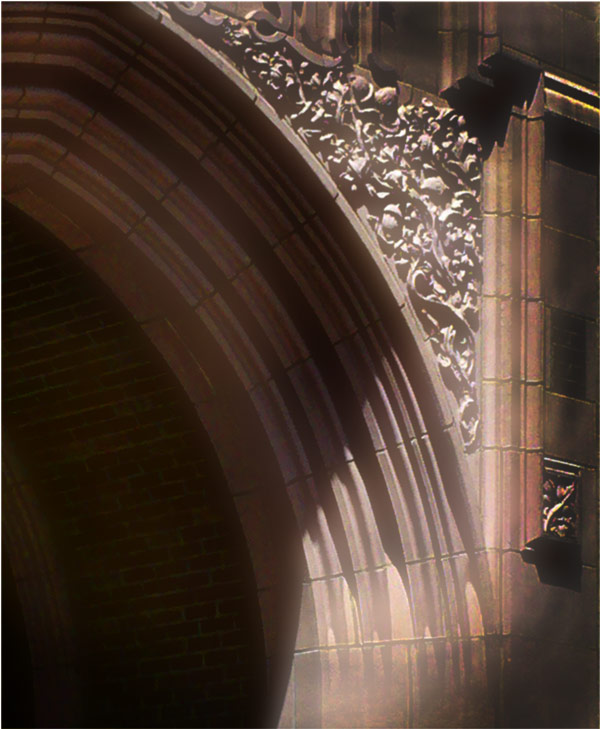

On Friday I became an art history nun and went into the cloisters. The University art library is not the place I recall from decades ago, but imagining persists. I ignore the flourescent tubes and the blinds drawn against the natural light of the clerestories and am grateful at least for the shadows of leaves cast by the trees. I pretend these silhouettes are a vintage theorem painting being painted again and again by the wind and the sun. I inhale the Dewey decimal system and its attendant odor of pulp and glue, and feel a calm and translucent habit settle about my shoulders. In this funnel of starched linen, a scalloped awning above my eyes, I can sink into pictures and footnotes and the zigzag worry beads of the alphabet. Some call this reading.

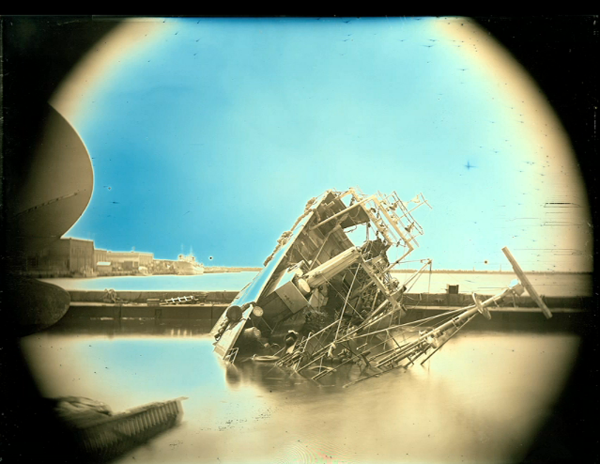

We live in a culture so laminated with derivation and appropriation that it is very easy to forget that at some point there was a “real” on which the derivations are based. An entire generation will grow up thinking that an Instagram is a photograph. “Snap a photo with your mobile phone, then choose a filter to transform the image into a memory to keep around forever.” “Retro” is a station on Pandora. “Retro” is, basically, a “filter.” But once long ago there were actual steam engines and eye glasses made of glass and men went under a tent of black canvas and made you sit still forever to get your one very precious portrait taken. I am so taken with these portraits. The person is dressed invariably in shades of umber, against an equally umber backdrop. She or he leans pensively, stiffly (whilst waiting an interminable ten to thirty minutes) until the exposure is complete. If you want to know what this sense of time is like, and how it sounds, take a peek at this extraordinary work by Takashi Arai.

In many historical daguerreotypes the sitter gazes at another daguerreotype in its lovely filigreed case, or poses the case facing out at the camera, creating a loop of self-referential mirrors. Is the person’s mouth twisted in a prematurely elderly grimace from the effort of trying to memorize the tiny image in their hand? Of trying to remember “who was this guy’s name who I might have been in love with at some point?” Or is it the tedium of south Dakota and the fly buzzing in the August heat and the fact that the pose must be held for half an hour? I find these pictures enchanting. The silver on glass does indeed cause the image to float, real and unreal, even in a reproduction.

Only later in the day, gazing at passersby at the Lake, am I startled to see that a glass case of identical size is being held by almost every person. And that they are gazing at this luminous device with rapt attention, admiration and even hypnotism, albeit in full technicolor and not sepia. They are also, in the style of modern liberations, moving their heads without concern, and emoting. And in many casts of light they are seeing their own face reflected over the latest status update on Facebook, which no doubt includes….Instagram photos. Talk about mirrors.

If a photograph was originally intended as an aid to memory, and as a document of the real, what is it now? How can you remember when you have no time in between images to forget? How many millions, trillions, billions of images will we be subjected to in our new modern lifetime? If we live in a world of endless mirrors, but without a mediating lense, light reflects but we do not necessarily absorb it, much less have the capacity to reflect upon it.

I have been dwelling on Batchen’s quote

“…the camera does more than just see the world; it is also touched by the world. Light bounces off an object or a body and into the camera activating a light-sensitive emulsion and creating an image.”

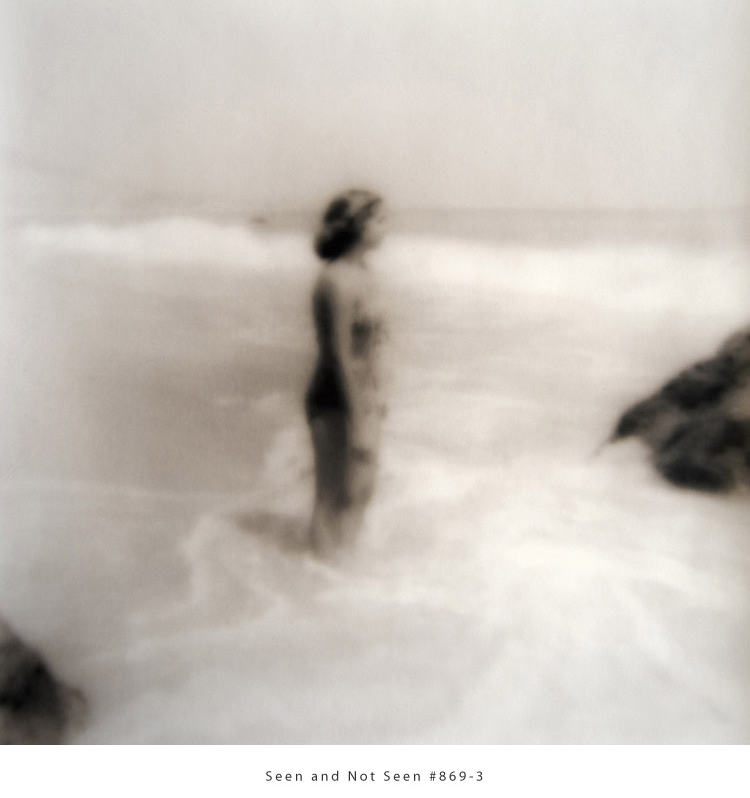

This idea remains magical. You can easily lose sight of it when you spend hour upon hour in front of a computer revisiting images that are now simply a pixel representation of a moment of touch. Most modern photography (and conversation about it) lacks attention to one elemental factor: emulsion. Invisible on screen or in digital prints, it is the thinnest of membranes, providing the alchemical medium between the world of touch and the world of sight. The essence of this was brought home to me during a lecture, “Seen and Not Seen,” I attended at the Pacific Northwest Center for Photography on Friday. This enchanted evening in the dark viewing the work of Ken Rosenthal provided the perfect elaboration of everything I had absorbed in the library hours earlier. The primary body of Rosenthal’s photography looks backwards into memory, and is based on personal and historical photographs of his own family. All of the work until very recently relies on darkroom methods for printing. The sense of the physical and intimate path of light comes through very strongly.

His methods are exacting and customized, and not entirely revealed. When I see these images I feel transported not just to the past of the event documented, but into the laboratory in which the image was made. One of Roland Barthe’s essays which I read this week describes at length the sounds of a photograph. The verbal description alone, placed next to the seemingly inert photographic reproduction of a horse walking in fog, conveys a sense not just of sound but of air and smell and cinematic immediacy. As I write this, sitting at a computer, having spent all of yesterday “developing” photographs in Photoshop, the convergence of Barthe and Rosenthal, like the bite of a madeleine cake catapults me into another time. I am on the farm in the darkroom, my eight-year-old nose bumping my father’s elbow, watching as he develops prints of an Arabian horse. It is a summer day in July, and we are in the only cool place in the uninsulated farmhouse, in the basement where he tucked a bench and an enlarger in a narrow hall behind the washing machines. I can hear the rattle of the film canister, the click of the enlarger moving up and down, the huf-huff of the dust bellows, the tongs knocking against the developer tray. The red light is terribly mysterious and exciting, and I know at any moment I could ruin everything by opening a door. And then there is the moment when my father lifts me up and stands me on a chair so I can see the image emerge, ghostly, intangible, then gradually an eyelash, a glint of bridle, the unmistakeable ridge of a mane rising up white against a dark unclouded sky.

What Rosenthal achieves in his approach to his own very personal subject matter is not “just personal.” It is about memory and seeing itself.

And it resonates in a universal way with anyone who has ever held a family photograph in their hand, run their fingers along the scalloped edges and wondered about the slightly out of focus and scratched up ancestors buried in the surface. As technology changes, as emulsion and eventually even the memory of emulsion vanishes, as “family albums” come as pre-designed digital templates with faux photo-corners and can be “downloaded” in seconds, although never actually “held,” as vintage or as for that matter everything becomes a “look” referencing another “look” I wonder how his work will seem in twenty years. What filters will viewers see it through? The metaphoric facts of how we see will not change. Memory will “blur” fact. The eye will continue to alternately focus on one thing and the whole, moving back and forth in time. Light will continue to refract, bounce, enter, transform. Perhaps the early technologies were closer to revealing the unseen than our modern ones in which part of the achievement is the pristine absence of gears and wheels. You will find many contemporary images mimicking the look of the ground-breaking running horse sequences of Muybridge but few of them mimic his idea, which was that he was showing something the eye could not see.

I feel a great solidarity with the artists today exploring alternative photographic processes. All of these methods attempt in some way to recapture the mystery of photography’s origins. Artifact, relic, moment, surface, presence. Something beyond the ever-unpluggable computer screen or the printed facsimile of the screen. An object that takes you believably into the moment both as you create it and as you witness its record. If we are using primarily digital technologies it is an open question if we can transcend them and find in the pixel a convincing fingerprint.

When I left Rosenthal’s lecture at nine o’clock the last of the Siberian forest fire sunsets still hung in the Seattle sky. Who would have guessed these translucent clouds and mesmerizing pinks come courtesy of Russia? The air shimmered with softness and unexpected warmth as I pulled my car over at a construction site. I propped the camera into chain link. Low light, no tripod. Under these circumstances I don’t usually think about the physicality of light, of how the camera is “touched by the world,” I tend instead to curse the limits of resolution and sensors and my human hand. But for this lantern hour as I shot into the deepening dusk, I let those thoughts go. It could have been another time: the world was young.