I’ve been settling into my new studio. Wordless for now…..

New Directions in Contemplative Art: Conversations with Artists

This week I am launching a new series of occasional interviews with artists working in the contemplative/devotional traditions. Many of these artists work within the rich iconography of Buddhism, and specifically with the image of the Buddha. Historically the Buddha is represented as a figure of serene composure, elegance and grace. The eyes look inward, closed or downward cast, the shoulders curve gently into hands held in perfect mudra. A careful ritualized mathematics guides the distance between folds in the Buddha’s robes and the size and placement of snails on his head. The surface is stone-hard or wood, impenetrable.

This is a statue, not a man–and certainly not a woman, although Greek influence gives his robes a lyrical sweep and his body is not the emaciated one of early more ascetic representations. Not just the province of practicing “Buddhists,” the Buddha image lives ubiquitously in the contemporary marketplace of imagery and ideas. The popular shorthand for “Buddhism” is the relinquishment of desire and a state of serene acceptance, exemplified by the immobile statue. The statue is an ideal. What happens when society fills its spiritual landscape with an image of an ideal rather than a real?

It sets up a struggle, a dichotomy, hazardous and blessed in equal measure. The essence of devotional art is an image and an ideal larger than the human capacity to realize. It is aspirational. And in aspiration is a keen and particular form of suffering: you never get there, you are always leaning towards, but never reaching. Modern life, at least as practiced in America, is about getting there: and it is about getting. There is grasping and a kind of avarice in that. As well, a valuable practical truth and wisdom. The democratic revolutions tumbled the monarchies: we can all consider ourselves kings, queens, or at least the head of our local precinct caucus. Darwin, driving a nail into holy hierarchies, established that we might be on a less than mystical trajectory from birth to death and nowhere does he tell us if the soul is an acquired or inherited trait. Given the melting ice caps we don’t know if we or the sutras will be here in 2020. It is only logical to say: why not now? Why not me? Why can’t I understand in my own terms, and right now, — quickly?

The membrane between the modern urgency to leap efficiently from aspiration to getting and a deeper, timeless and more thoughtful understanding is being explored by the artists, writers and other creators reinventing religious iconography on their own terms. Some of them continue in the lineage of traditional forms, repositioning them in modern environments. Others take the sly point of view, working in illustration and advertising, and others work from the ground up re-inventing the very iconographic forms, with their own personal and aesthetic mathematics. Irony is rare, and to me this is a welcome blessing. These artists are not afraid to wear their aspiration on their sleeve. They may risk condescension and accusations of blasphemy from the spiritual establishments, and incomprehension from the secular consumer, and yet they continue on.

As someone who has followed the Buddhist path– with some detours– for most of my adult life, I want to talk to these people. The Buddha image in particular has huge resonance for me. I have done and continue to do visual art, or what I think of more properly as contemplative practice, that incorporates the image of the Buddha. This practice has led me towards viewing my own art making, regardless of the subject, as an extension of contemplation, primarily motivated by a desire for insight, beauty and emotional ballast, and secondarily as an object in the marketplace. I look forward to visiting the studios and work of artists with a similar perspective, and to seeing the varieties of ways in which their practice takes form.

Please check back from time to see the latest artists interviewed in the category of “The Mystic Muse“, or subscribe to receive this blog in your mailbox.

My companion in travels, the plug-in-‘88 Toyota-cigarette-lighter-laughing-while-driving-Buddha. Factory made in a high-stress environment by card-carrying atheists, no doubt.

“100 Objects” Part Two: Art as Devotional Practice

I have slowly been working my way through “A History of the World in 100 Objects” (see previous post.) I have given up the idea of dutiful chronological study and instead I choose chapters at random. Last night I landed on “Gold Coins of Kumaragupta” and found a passage on Hindu worship that struck me on multiple levels:

Hindus will see a deity, on the whole, as God present. God can manifest anywhere, so the physical manifestation of the image is considered to be a great aid in gaining the presence of God. By going to the temple, you see this image that is the presence. Or you can have the image in your own home — Hindus will invite God to come into this deity-form, they will wake god up in the morning with an offering of sweets. The deity wil have been put to bed in a bed the night before, raised up, it will be bathed in warm water, ghee, honey, yoghurt, and then dressed in handmade dresses — usually made of silk — and garlanded with beautiful flowers and then set up for worship for the day. It’s a very interesting process of practicing the presence of God.

–Shaunaka Rishi Das, Hindu cleric and Director of the Oxford Centre for Hindu Studies

There is a wonderful poignance to this image of bathing the deity, of feeding it sweets, of dressing it — such tenderness. It made me think, where do I practice this in my own life? And do I practice this in my work?

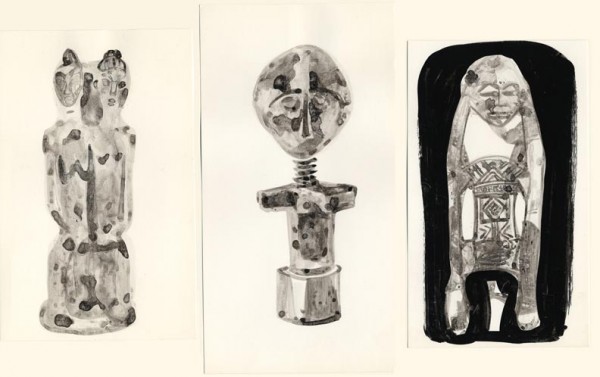

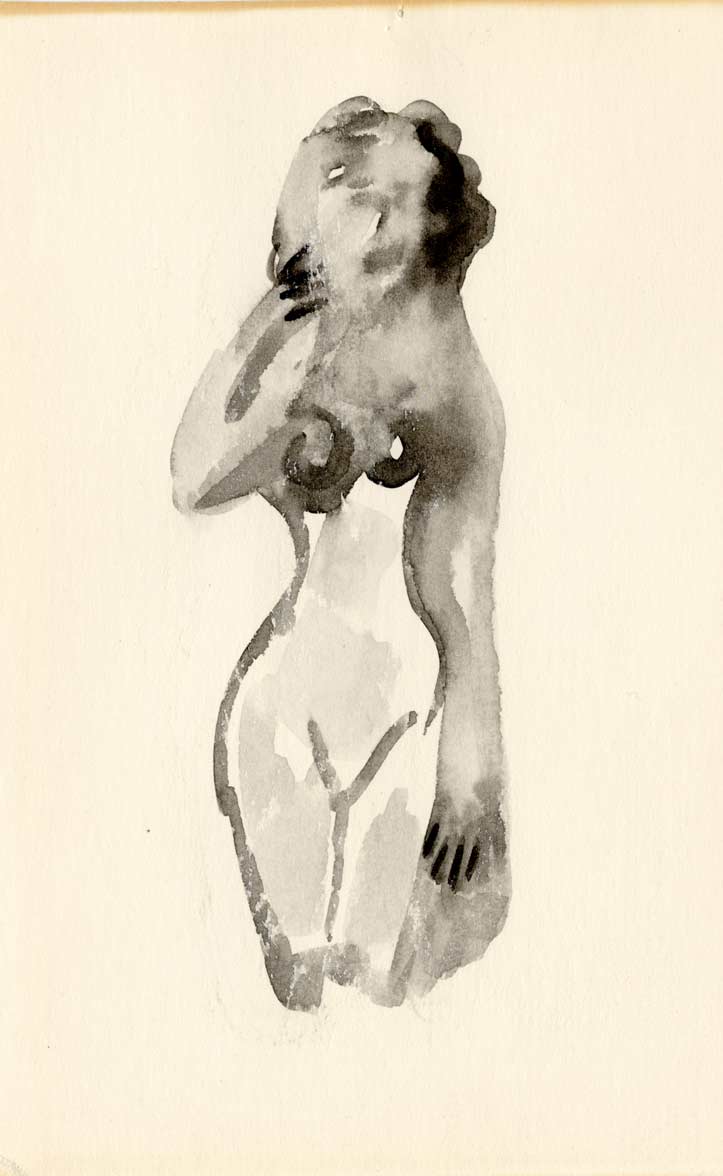

In the process of designing the new and revised version of my website I have been going through my archives and deciding what to add in, keep or delete. After sleeping on the passage above, I remembered a series I had done a long time ago which reflects this same devotional impulse, although not in a Hindu frame of reference. For about a year I painted hundreds of small studies of African fetish figures. I used books on African sculpture as my reference, and did my studies the way I would practice kanji, repeating them over and over again, on different papers and with different paints and inks, trying to allow the “figure” to become part of me. The practice became a mobius of energy between myself and the ritual object. The koan was “what is the self?”

The figures fell into fifteen or twenty different tribal archetypes including a woman holding her head, her body or her baby, a figure holding a mirror, a figure holding a drum, and a recurring double figure, two conjoined in various ways. The paintings’ very smallness helped me to keep the practice devotional. I wasn’t creating anything for a “wall.” But I was inviting the gods into my house. It is good to remember to open that door.

Sleep Studies: Paintings Inspired by the Ex Voto

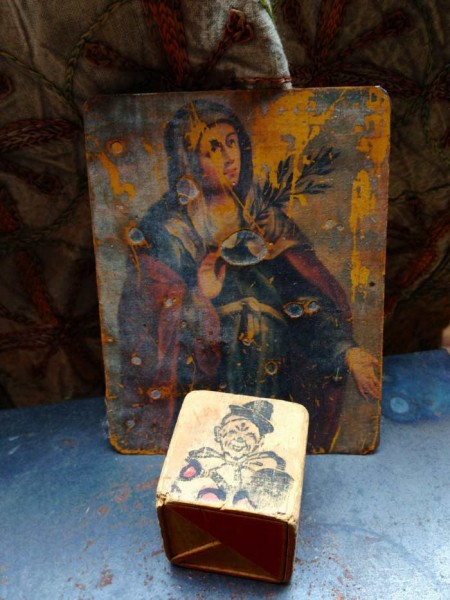

Years ago I spent a month traveling in Mexico, where I picked up a very old ex voto painting on tin. This traditional form of devotional painting shows the narrative of a spiritual or mortal crisis and its resolution. On the earth, people pray, more often than not someone lies sick in bed, and in the heavens a saint floats, all ears to the prayer scrawled in Spanish across the picture plane. The bed frame has always haunted me as an object of power in its own right. Unlike the chair so often depicted by artists as a stand-in for human attitude and contemplation, the bed usually has no arms, and often neither foot nor head. It sits unadorned, a naked platform on which to project our own memories, dramas and introspections.

This series of paintings started with the desire to experience the ex voto on my own terms and in my own culture. I do not believe in the saints. The only apparition that ever appeared in answer to my skyward yearnings was the GoodYear blimp, which revealed its private message to me in red neon in 1972: “Drink Coca Cola.” I’ve been looking beyond to the rosy sunset for years, wondering. I do not believe in the saints, but I do believe in their shape. I have always found consolation in the forms of devotional art, as though even in cultures and belief systems foreign to my own the abstract language itself has meaning.

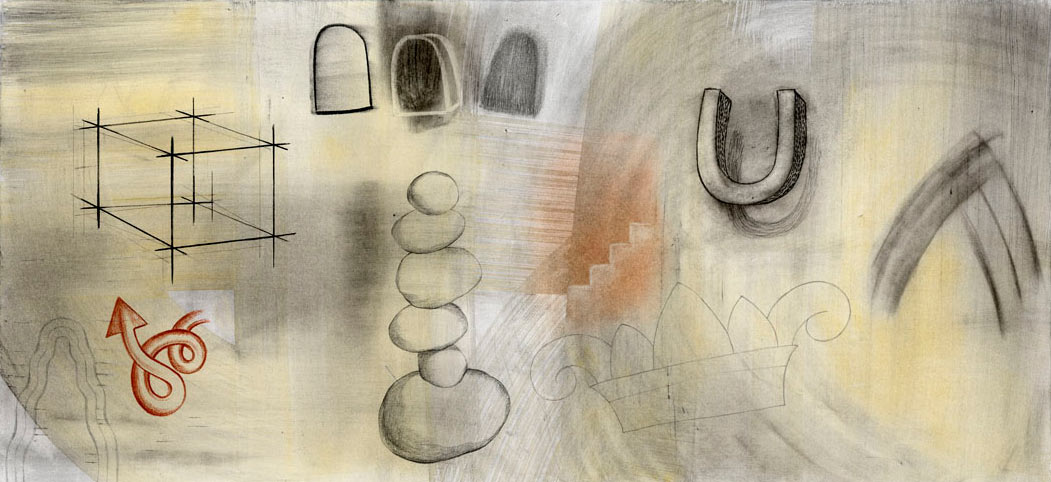

As I worked on these images the forms evolved back and forth between story, recognizable symbol and abstraction. My working method starts with careful sketching of composition, stencils and color study, and then I throw up my hands and go with whatever the painting seems to be asking me to do. All of these images are original paintings created with printing ink applied directly to paper without a press.To see more in this series go to Sleep Studies.