I visited Fred Lisaius at his studio in the Inscape Building on a bitterly cold day in early spring. As I drove into the parking lot off of Airport Way hail clattered on my windshield and dark clouds billowed to the west. I stood and looked up at the building and felt a chill not just of temperature but of the building’s history as the Immigration and Naturalization Service, a holding tank for immigrants, an outscape at the edge of America’s by-invitation-only hearth. Even as it transforms into a new magnet for the arts, with studios for eventually up to 100 artists, the building retains a sense of its former purpose. It exudes a seriousness and a darkness and graphic remnants of its history remain, like the graffiti written in tar by inmates gathered on the roof under hot summer sun.

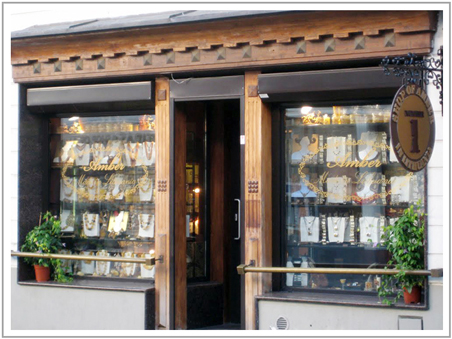

I had always admired Lisaius’ tapestry-like paintings of flowers and birds set against old-world skies. He is a master of detail and surface and his color harmonies give the viewer a sense of peace and elation. But what provoked me to call him up was his new series of sculptural works a the SAM Rental/Sales Gallery. These mysterious cast resin pieces are a modern re-creation of amber. In travels to Lithuania Lisaius discovered entire towns devoted to this ancient precious stone.

He became fascinated with it, and especially by the inclusions: insects, plant forms, wood and other fragments of life frozen in pine resin from 50 million years ago. As he traveled through Europe he collected found objects and scraps of printed material that captured his attention, stashed them in his pockets, and brought them home. Now they emerge in collaged assemblage, frozen in resin, insects of his own creation.

In the amber world there is much discussion of what is fake. How do you know if it is bakelite? Or worse yet, imitation bakelite? Have you immersed it in water, and does it sink or float? Is it unnaturally clear? How do you know if it was in fact the result of the romance between the mortal fisherman Kastytis and the sea goddess Jurate whose undersea amber castle was destroyed by the Thunder God–? Are the beads in the market fragments from this castle, washed up on the shore? Or merely factory simulations?

Lisaius’ pieces are great fakes, because they make you stop and consider what is real. We live in a time when impending global extinction makes everything more precious, and simultaneously worthless: how can we afford to mourn each leaf, each butterfly, each minnow, or even every human life lost in today’s 40+ wars? “Real” amber entraps the fly-wing and the spider of prehistoric eras for eternal retrospection. Lisaius’ entraps one person’s memories of time and place in poured resin. If humans are still here to put things in museums thousands of years from now the chance ephemera of this day may seem as rare as the ancient Baltic termites in Palanga‘s amber museum.

At a certain point in our conversation the rain and wind briefly lulled, the sky threatened sun, and I looked up from my cup of instant coffee to throw out the word “souvenir.” “Non, non” Fred protested, “not that at all.” But I love this word. From the original French it means “remembrance or memory.” We tend to translate souvenir into “cheap trinket:” something sold to us by a multinational corporation made in a country continents away from the one in which we are standing to make us remember somebody else’s idea of what we have experienced. Here is your trophy of the Eiffel tower. Here is your velvet-flocked buffalo from the badlands of Dakota. At least it’s small, cheap, and ownable, unlike the actual thing. In an era of upheaval and extinctions the souvenir of memory itself becomes perhaps more precious than anything else. Here we suspend our experience in time as our possession, to share with others as stories, to build our pictures from.

As our time came to an end I asked Fred how his sculptural work has influenced his painting. He said that the suspended insect inclusions in his amber pieces had led him to consider “suspending” an object in a painting. So I leave you with this haunting last image, the immigrant duck floating towards what she knows not.