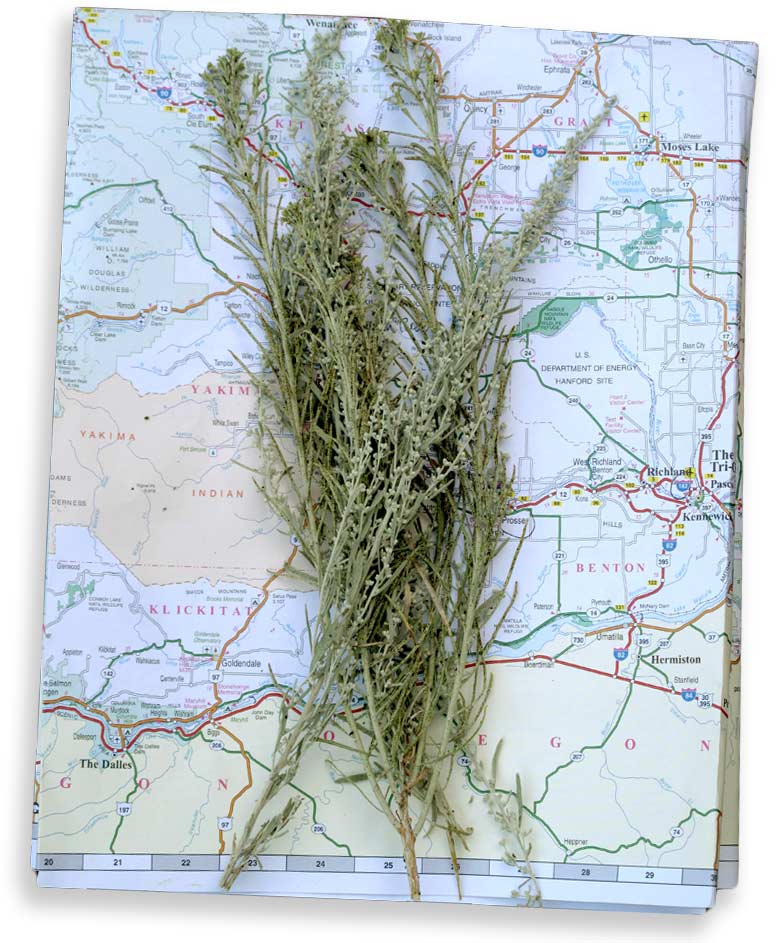

Weeks after returning from Eastern Washington, I can’t seem to put the map away. From the corner of my eye I see the blue of the rivers and the lakes and the pale butter of desert and wheat. The whole map seems cast in the blue of the sky. It keeps me on the road even as I stand in my kitchen looking at weather the color of concrete. I read the names of the towns and put them together, knowing I would believe these people were real if I read them in a story: Clayton Ford, Lamona St. John, Gilmer Packwood, Randle Bingen, or just plain Quincy, with no last name. I want to have a cousin named Mayfield, and I want to marry a man named Dusty, which lines up along the road to Othello right next to Hay. To look at the map, to be in the map, they infuse each other – the blue sky the same color as these meandering backroads. The names of these places are equal parts dirt and aspiration. Yes to the beat up range horse and the saddle whose rosette tooling has worn flat from years of use, and yes to the Spokane carousel whose horses bloom with gilded chinoiserie.

Weeks after returning from Eastern Washington, I can’t seem to put the map away. From the corner of my eye I see the blue of the rivers and the lakes and the pale butter of desert and wheat. The whole map seems cast in the blue of the sky. It keeps me on the road even as I stand in my kitchen looking at weather the color of concrete. I read the names of the towns and put them together, knowing I would believe these people were real if I read them in a story: Clayton Ford, Lamona St. John, Gilmer Packwood, Randle Bingen, or just plain Quincy, with no last name. I want to have a cousin named Mayfield, and I want to marry a man named Dusty, which lines up along the road to Othello right next to Hay. To look at the map, to be in the map, they infuse each other – the blue sky the same color as these meandering backroads. The names of these places are equal parts dirt and aspiration. Yes to the beat up range horse and the saddle whose rosette tooling has worn flat from years of use, and yes to the Spokane carousel whose horses bloom with gilded chinoiserie.

Here in The West, in the upper left-hand corner formerly known as The Oregon Territories, (and before that as the land of the Nez Pierce, the Quinault and the Yakima Nations), we are divided by mountains. The usual associations of the compass don’t hold; The “East” is not know for its Buddhists and pagans and barefoot Occupiers but for small towns with even smaller churches with firmly held conservative beliefs. The West curls its lip at the East and mocks its Bible-quoting politicians and lack of tender regard for restoring the gray wolf. The East would prefer not to sponsor seawalls and fancy underground freeways and weddings in which both the bride and the groom are named Meg. And yet for all its smug urban insularity, people of the West regard the East with nostalgia and they carry a certain ache for its rural beauty. Out there is the land. No matter how thick the condominiums or how constipating the traffic or how high the price of a double latte vente with vanilla on the west side, the land is out there just over the pass saying: we have space and sky here for you. It’s saved for you and in the bank: beauty.

Every few years I make the pilgrimage across the Cascade mountains, to see if that space is still there or if I imagined it. This August I went with two artist friends to stay on a farm outside the farming town of Pomeroy and look after a herd of goats. It was delicious to be with companions who live to stop and to look. We packed a week of lunch, and checked our brakes for the long steep slope down the other side of the mountains.

After a bit, beyond the too-big fruit stand that is now the only fruit stand, in the town of Thorp whose name seems too short and where the massive marquee offers “Antiques | Fruit” which just makes us think of raisins; after that bleak stretch where we think we’re not anywhere at all, we do reach The Road. Here finally is the ribbon of hills. The folding and unfolding waves of gold and green pivoting into creekbeads and scree and broken down things. Shimmering asphalt, blazing hairpins, the river, the barges, the Falls. White butterflies in pine trees. And a sudden leap into science fiction. When did the land become a wind factory? I turned my back and the Germans came and put these white giants, these three-armed industrial starfish on every horizon. What would Ray Bradbury think? Would he lie down beneath them in their protective mote of gravel and toast them with a glass of dandelion wine?

Each windmill earns a farmer $10 thousand dollars a year. Each windmill powers 350 houses. Put that up against an idea,– a relic of an idea — of “landscape” or “natural beauty.” You’ll lose. And so we go farther east, to where the migration hasn’t taken hold, practicality and beauty are in harmony, and the highest best use of land is wheat and peas and these are just coincidentally lovely. [Read more…]