For as long as I can remember my father had a painting of a man hanging in his study. As a child it seemed huge to me, larger than life: a wall-sized man. Surrounded by books on every side the man was, appropriately enough, reading a book. As I grew older I got tall enough to reach eye-level with him, and my appreciation for the painting grew. His profile was a jumble of brushstrokes that distilled only at a distance into a face. Such gravity and focus, the page held down with his burnt orange thumb, the air vibrating with color and stillness: the man was thinking.

On several occasions I said to my father that at some point (a point delicately not specified) I would like the painting, and he said yes, of course, although being a man of vivid life force he would immediately turn then to the photograph of Tolstoy and begin talking about Anna Karenina or perhaps The Political Situation or his next piece in the paper, for he published a newspaper in a small conservative town and each week he chose some subject sure to cause another advertiser to abandon him—perhaps Indian fishing rights, or the railroads or the unions or the war in Vietnam. He would take a breath after one of his long sentences and invariably mutter, the bastards. Sometimes I would tiptoe into my father’s study when he wasn’t there and push the keys of his massive Underwood typewriter, or study the pencil drawing of the wooden mask by Indian carver Lawney Reyes. Framed by two walls of books, the eastern window looked out at the Cascades and the ridge in front of them where at night the coyotes gathered to howl, with or without a visible moon.

The painting, the mountains, the room, the floor to ceiling books, all became melded into who my father was to me. When he died, due to the inexplicable dynamics of his third marriage, his belongings and the contents of his last study were locked away and his children received nothing. I thought of the painting every day, visualized every brush stroke, lay through night after night of insomnia and sadness longing for this physical reminder of who he was. One night five or six years after his death I had a dream in which I hired a thief to break into the study and steal the painting. In short order the thief became me, as I put on long white gloves and picked the lock with a skeleton key and hurled the painting into the back of my car, pursued by a procession of former in-laws. When I got the painting home I discovered that it had been painted over: it was ruined. I woke up distraught, yet oddly relieved. I had been freed, and that was the point at which I began to forget and let go. Ten years later, through circumstances equally inexplicable, the painting, the real painting, was given to me. And in a moment eerily reminiscent of the dream, I looked at it without recognition, even with disgust—and I put it in the attic and thought nothing more of it.

________________________________

An object is not a fixed thing. The more we look at it, or look away, or expose it to sunlight or pull the curtains the more it changes, as do we. Just as the most dazzling color is often fugitive, so is memory and the meaning we give it. In the years that the painting sat in my attic I began to collect art. The only faces I have permitted on my walls are wooden masks from Guatemala. The only body is not a body, but a coat with wings. Although I have painted hundreds of figures it has never occurred to me to hang one on the wall. Perhaps it’s that my mind is so peopled with the daily chatter of the mind that one more guest would be just too much. So in my home I am surrounded with animals and skies and temples and ambiguous surface that lets me dream my own dream.

All of this changed one night this week when I had the unexpected pleasure of visiting a collector of Northwest art. Although the house has been revised it remains mid-century, and the collection goes back in era to the greats: Callahan, early Cummings, Kirsten-Daiensai. I heard the amazing stories behind each piece, and studied the Callahan up close. As we sat in front of a fireplace of tumbled slate, I felt myself placed in another time. “What would you do to that slate wall?” the question came up. And the answer was “Nothing, it is perfect as it is.”

I have never been a fan of painting from the fifties. And having grown up with it, I have always detested mid-century modern: the blonde Danish tables, the molded fiberglass aqua chairs, the top-heavy lampshades on contorted ceramic bodies, the fabrics with tv-shaped lozenges and the flowers drawn to match the antennas and the aggressively angular couches and the beige. I never could bring myself to hate the slate. Perhaps it was the slate, and studying its random-but-not mosaic above the fire that turned my mind sideways. Or seeing an original Kenneth Callahan hanging in a house and not a museum, with Christmas lights tugging at me and a wild storm raging outside. I came home and went directly to the attic and pawed through the insulation until I could find The Painting.

I pulled it out into the light and gasped: it was beautiful! I wiped the cobwebs off and the layers of dust. The frame had splintered here and there, but still sheltered him in his moment of thinking, the orange and blue and black reading man.

I knew the name of the painter, Al Friedman, but that was all I knew, and I had no idea who the portrait was of. I reached out to touch his suspenders — suspenders! And that shirt, so white-blue, slightly rumpled, so surely a shirt meant to be worn just that way. He was still, and actually, larger than life.

I sat down to google Al Friedman. He doesn’t exist. Many many Friedman’s exist who are doctors and lawyers and even well-known cartoonists, but not my Al. I tried spelling his name every known way. I called my mother, and she said he was a cabdriver, that’s all she knew. He had driven cab with my father and his best friend. She and my aunt had tried to find him in the sixties in San Francisco and he had disappeared, though it was rumored he was married, and the last anyone heard he gave up painting except he did paint paper bags for a paper bag company. I called my cousin, and she said she had one of his paintings too, and she had also tried for hours to find some mention of him on the web but found nothing. All we could do was squint together and remember back to a dim sense of the rooms, the long dinners over spaghetti, the wine and unfiltered Camel smoke and the feel of our baby cheeks pressed against stretchpants with seams and stirrups and the adults, always shouting to be heard on the subject of The Political Situation. My cousin’s painting is of men at a bar. “I don’t like bars,” she said, “Why would I want a painting of men drinking at a bar? But I love it. It’s beautiful. It has a whole wall and it’s the only thing on it.”

Last night we hung the painting on the big wall in the dining room that had been waiting for something just right. I went into the kitchen to do the dishes and I couldn’t stop looking out into the dining room to catch sight of the Reading Man. I think I was checking to see if he would change back again, into the painting I dreamed, and hid in the attic and never wanted to see again. But each time he was there, beautiful, thoughtful, and steady: I had a guest.

Coda: Al Friedman, painter, apparently exists offline only, in what they call real life, in the memories of the people who knew him. I would like to know more, and if you were a friend of his, or collected his work, please let me know, and send me photos of his work. I would love to post his paintings here.

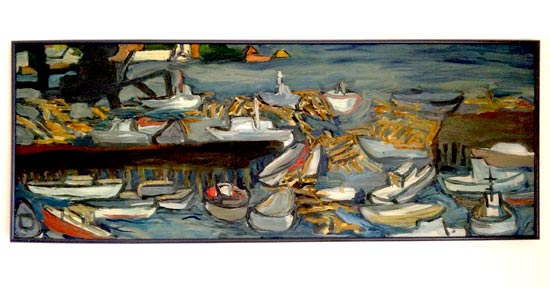

And here is one of them– thank you cousins!

Leslie says

Loved this post. I’m so glad you pulled this painting out of your attic Iskra. I’m a fan of mid-century art and design, and definitely this style of expressive painting. I look forward to seeing it in person. I hope more Friedman’s surface because of your post.