Last month I traveled by air for the first time in three years. Since March 2020 pandemic had kept me on a short leash between yard and living room, paying off the bills for cancelled trips. During this time I shrank my world to the space allowed and let myself forget how much I love airports, that vast impermanent canvas where the elegance of infrastructure and messiness of human drama intersect. I had also forgotten that an airport is not just a means to a destination, but a state of mind.

My favorite part of the day is the seconds between sleeping and waking: the space between. “Liminal state” is the term for that which is neither here nor there, and it’s a territory of enormous freedom. In an airport the liminal reigns. You aren’t supposed to be anywhere: your only duty is to look out the window. There, from your rocking chair in the Knoxville Recomposure Station, or the bar in Houston, you are completely justified in simply admiring the tarmac. A labyrinth of geometry and human industry, it is well worth study, however long the layover.

The soundtrack for this travelers’ cinema, and for my creative journey, is inextricably entwined with Brian Eno’s Music for Airports. Probably no other music has affected my way of working and seeing the world more than this seminal album from 1978. Eno and his band of ambient brothers gave authority to the dreaming imagination and sparked an entirely new genre of music. On first hearing, (on a Sony boombox), it became my home. When I began traveling for work as a typographer and designer I discovered that artists in Denmark and Holland were also inking serifs and coding alphabets to Harold Budd, Lyle Mays (listen to the aptly named Before You Go), Eno, Eluvium and others. Standing at a conference in Oxford trading music with Danish type designers, knowing that at 2 AM we were working to the same sounds, brought the world full circle. It also meant that I wasn’t crazy to value ambiance, and by extension visual atmospherics, as much as drama and plot.

I did not expect to come home from a journey to see fireflies in Knoxville to make 18 prints about flight. But two things happened en route to my destinations: the Houston airport stripped off its carpet and left a concrete floor, and I had a conversation with a stranger on a plane. What happened next is either a case of attention deficit syndrome or simply what it is to be an artist.

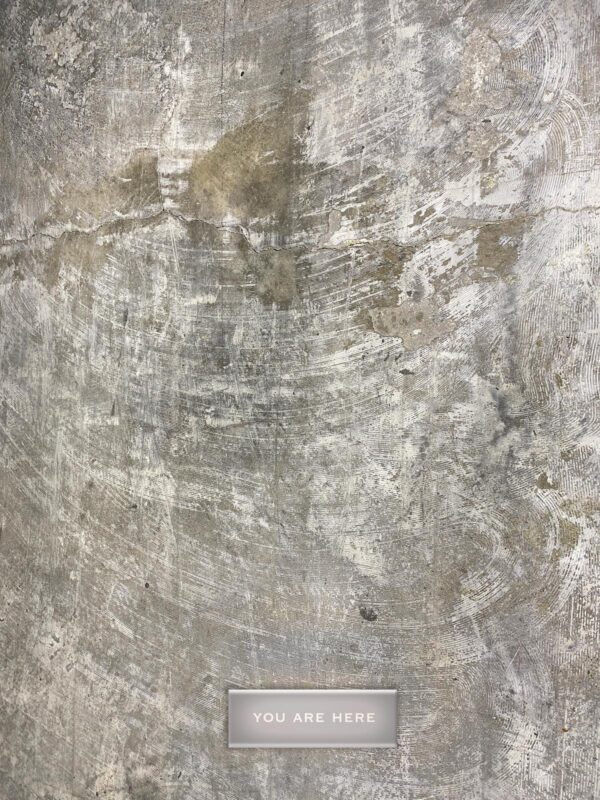

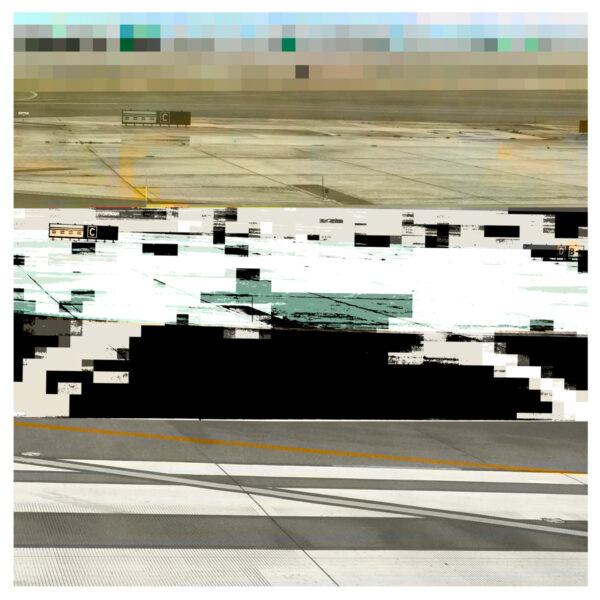

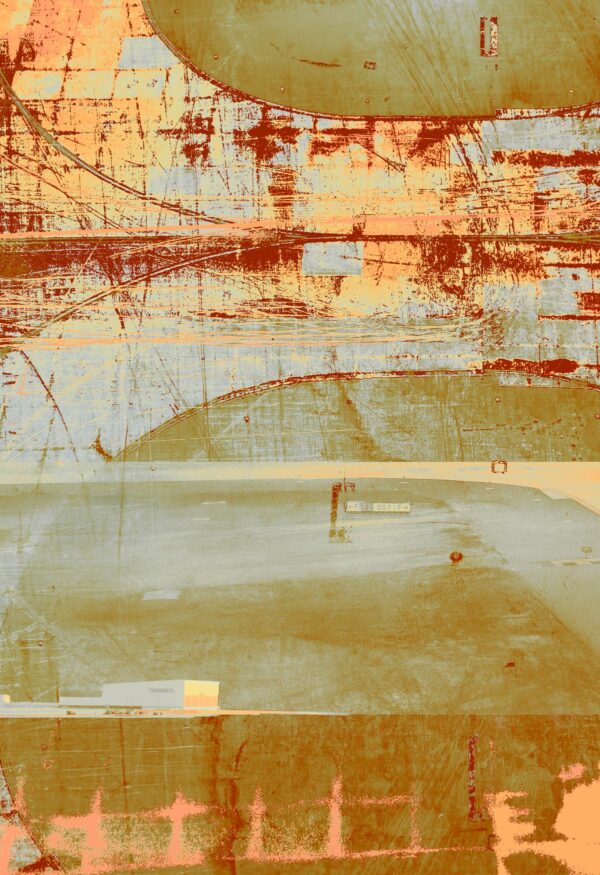

In much of my work texture, and particularly the distressed surfaces of construction sites, are the runes that begin my process of seeing. The Houston airport, fortunately for me, is a massive construction project. As a devotee of surface, nothing could make me happier than to wait for an hour while looking at raw concrete scarred by trowels, adhesive and traces of old carpet. At the gate I immediately turned on my phone and began documenting as much as I could without looking like someone out of their mind. How do you explain to a harried mother with a diaper bag and a screaming child that the floor her luggage is tripping over is beautiful, a zinc plate waiting for the press…?

We boarded and I settled into my window seat. I had begun editing photos when my seat companion arrived. He was tall, young, and a natural extrovert. We launched into a conversation for half an hour that I can only describe as a moment of high art. Every thought led to another better thought, and as the world populated with new ideas we both seemed absurdly smart. He was an entrepreneur, and unlike every other person I spoke with in the Texas airport his business was not “oil and gas,” but ideas. I cannot recall all of the conversation, but one thing stood out. He said although he did not do social media, he still had a hard time concentrating due to chronic Fear Of Missing Out. How did he know if he was at the best place to be at any given moment in time? How could he be completely “here” if he couldn’t be “there?”

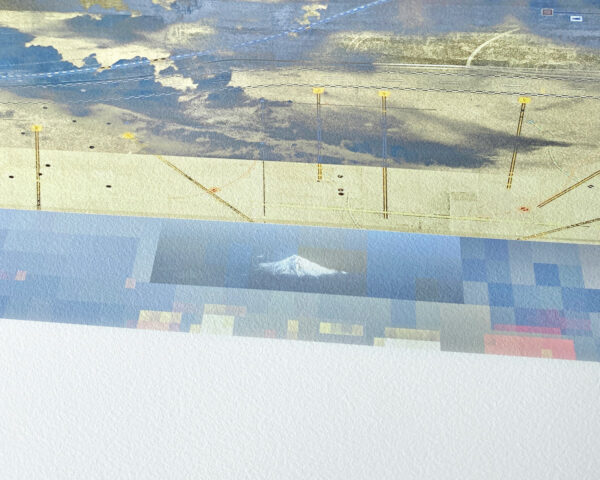

I showed him the photographs of the floor, and the collages I had been making on my phone on every flight, based on exactly what I saw in front of me. You are always right here, I said, you just have to look. He then nodded and leaned forward to put his head against the seat in front of him for the time it took to get to Denver. I settled into my work, photographing clouds. When we landed he sat up, we smiled at each other and went our separate ways. I came home and made 18 new prints, which I am calling The Tarmac Residency, an experience of being exactly where you are.

Investigations Into the Flatness of the Earth

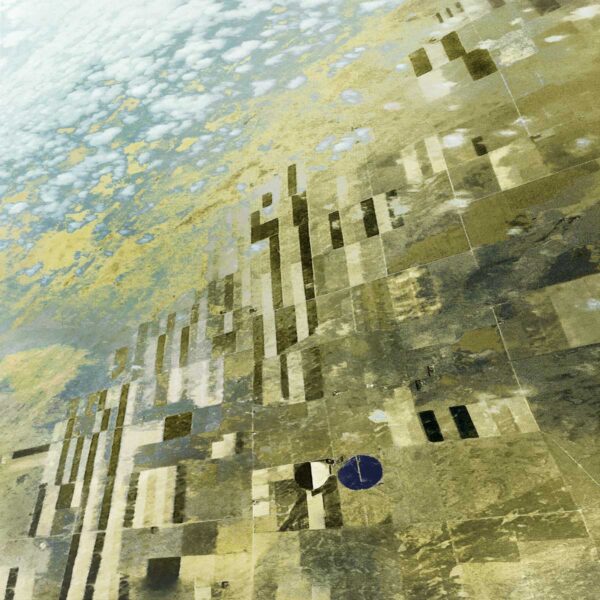

Travel invites a radical shift in the sense of our own size in the greater scheme of things. The first time I flew into San Jose my body seized with breathless panic at the scale of what I saw from my window seat. There seemed no boundary to the infinite confetti below, the grids of homes and offices and streets, the serpentine interruptions of highway, the scattered blue squares. They continued until blurred to the edge of the sky. All those lives. 1,305,004 give or take a thousand on that particular day. In my seat I felt myself become smaller and smaller and with this shrinkage came not relief, not a merging with the whole, but a sense of immolation. My existence did not matter at all.

I landed, my cousin greeted me with her dog, and the first thing she said, frowning and stroking the animal’s head, was “She is very upset, she has a tick in her ear.” In that moment the airplane continued its landing deep into the chambered topography of the ear, zooming deeper and deeper until it located finally the infinitesimally tiny, unseen but deeply felt tick. The sense of my importance in the scale of things has never been quite the same.

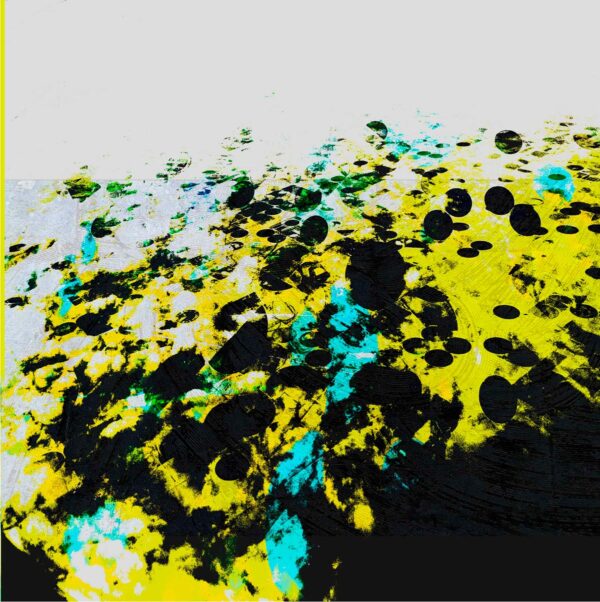

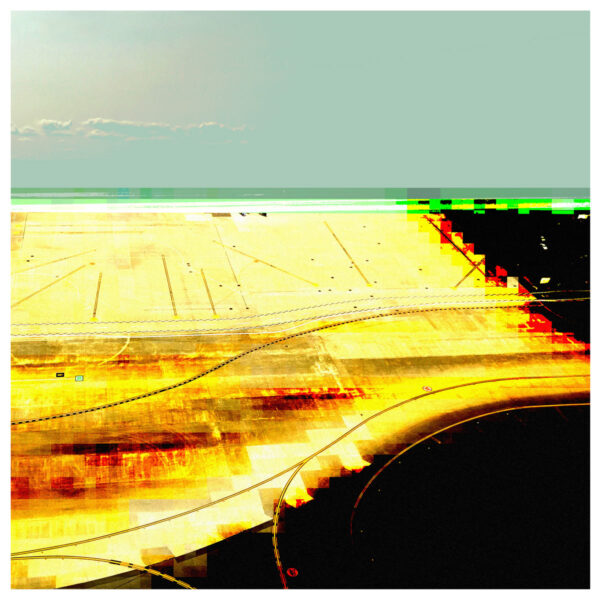

The recent movement to re-establish the flatness of the earth is in part a response to the desire not to feel so small. Flying is definitely a way to explore the hypothesis of the earth as a squashed orange, not a round one, so popular on YouTube. As Cezanne and other painters going back to the Egyptians have known, “Flatness is a Thing.” This first suite of four pieces is my contribution.

A Conversation Between Music and Art

I often begin pieces on my phone, using apps that can blend and collage images. They have a certain magic on a three-inch screen, but are not printable as fine art. When I go into the studio I take the sketches and deconstruct them, recreating them at high resolution so they can print in larger scale, up to 30×30 inches and sometimes larger. In the process of doing iterative version after version the work evolves and changes many times. As I developed these images, with ambient music filling the room, I began to think about the digital “looping” that forms the infrastructure of digital photography and of modern life. It occurred to me then to introduce the graphic structure of the pixel into the images as part of the weave.

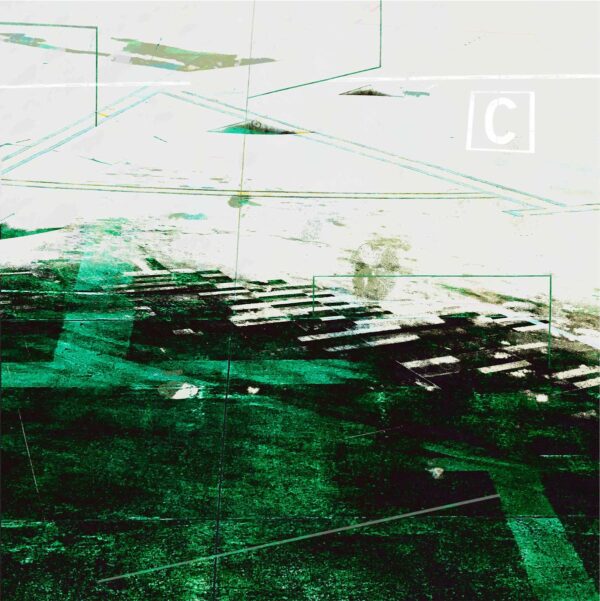

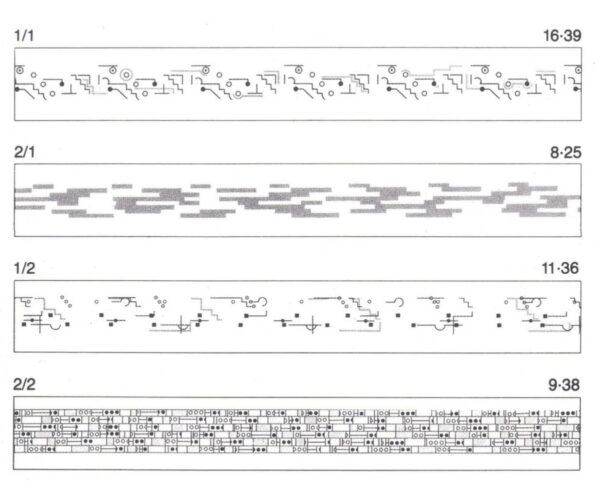

It was not until after I completed this series that I went back to the source, the music, to remind myself of the origins. In my research I came across a site called Reverb Machine, and a deconstruction of the iterative process of making Music for Airports. Brian Eno’s liner notes are there, in a graphic language resembling Navajo weaving, and in the shape of primitive and distorted pixels. I saw these images after creating the work in The Tarmac Residency, and it is uncanny that the image process that evolved in my work while listening mirrors his own notations from over thirty years ago.

As I worked on the landscapes the language shifted back and forth between atmosphere and structure, now architecture, now map, now dream.

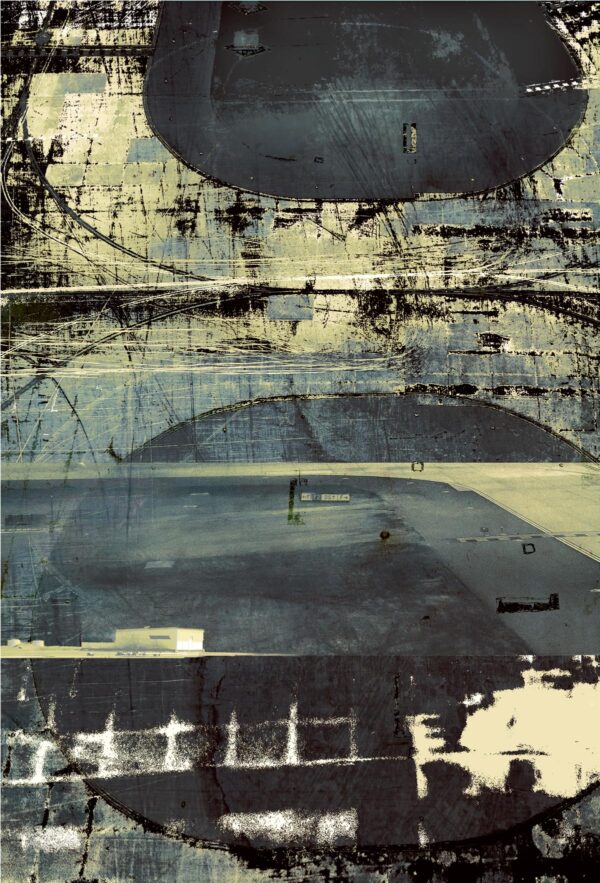

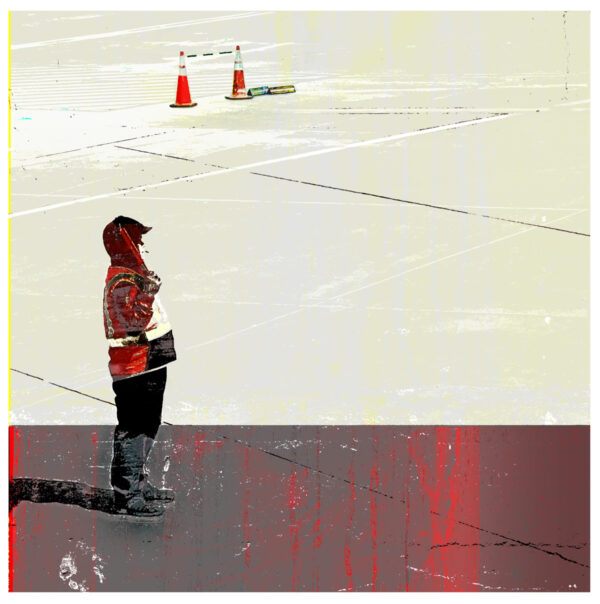

The Ramp Agents: Airport Semaphore

I am fascinated by the men who move through the transportation landscape, how essential and yet incidental they, like so many of the people who are part of infrastructure are. I looked at the job requirements on Indeed: Must type accurately 30 words per minute, be able to operate forklifts and other heavy equipment, have the ability to lift luggage that may weigh 50 pounds or more carefully and courteously, smile and be polite, work outdoors in all weather, nights, weekends, holidays, withstand deafening noise, and so forth. Yet what we see from a comfortable seat on the plane is a uniformed actor moving from wing to wing, shadow to light, the lines beneath his feet like the lines of jump rope, shadow and rope trading place as the day goes bright and then dark. The orange wands the figure holds perform the semaphore that keeps everything running, and from running into everything else.

I have been back on land for four weeks. The sky does not look the same. I have many more ideas for this subject, and hope to find collaborators to produce work for site specific installation. The series is available from SaatchiArt in limited editions in different sizes, and can be produced on paper, canvas or face-mounted acrylic. The work is also in my print portfolios, and new pieces will be added there.

A digital screen does not accurately convey the physical nature of my prints. I use an organically textured rag paper from Hahnemühle for most of my work. These are fine art prints, custom printed and signed. If you in the Seattle area I am happy to set up a studio visit so you can see the work in person.

Leave a Reply