New Directions: Western Landscape Photography Part 1

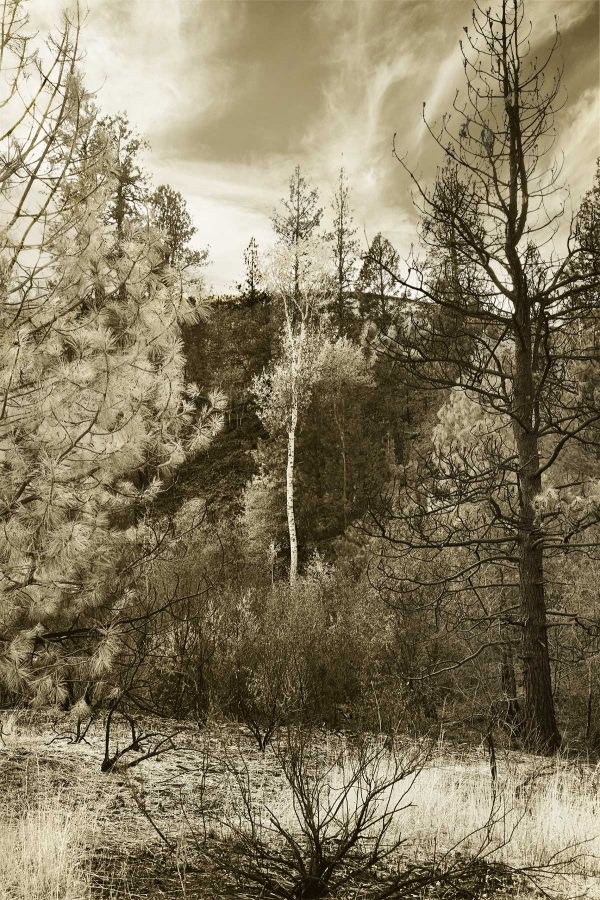

Today I have been living with this tree, captured originally in full color (though muted and overcast) in a forest east of the mountains. I say, “this tree,” but you, the viewer, might not be seeing the same tree I am. You might be seeing the tree on the right, scorched by fire, and interlaced with the bleached needles of a pine that may or may not see spring. I am aware of that tree also. But in the moment of stepping into this meadow what stood out against the uneven and patchy hill was the shimmering tree with yellow leaves and white bark. In a soundscape emptied of birds the wind in its leaves made the only sound.

As I go back in time to this moment the digital darkroom allows me to ask “What is this story about?” countless times, and each time to come up with a different answer. A voice I’ve heard often says “People don’t like dark. Make it light, make it hopeful.” Leonard Cohen speaks up on another station and says, helpfully “Make it darker,” as for that poet the darker the shadows the brighter the illumination. In developing a photographic print I cycle through decision after decision, undoing, saving, revisiting, doubting, knowing, unknowing. Each revision of value rewrites light’s story, saying: the point is the mountain, or the pines, or the sky. Finally it may land on this, perhaps a tale of the heroine in white, surrounded by courtiers and knights and armies in the distance.

In the forests around Yakima the shape of the aspens tug at a memory of the archaic, and make me think of Joan of Arc in a book I saw as a child. The pages of the book were engraved and brown at the edges, pungent with age. Joan sat on her horse deep in a copse, her armor camouflaged by dappled light, her sword glinting. The style was detailed, each leaf individually drawn and burnished against a pewter sky. In the grove, momentarily safe, Joan was thinking, and gathering herself. On my hikes I kept looking for her, expecting her to ride forth, tossing her hair as she leaned under a branch, turned a corner on the trail, and paused to look out into the distance. What would Joan have said? Dark or light, or a middle tone? I am not sure, but her horse would have led up the canyon into the fire, which was still smoking.

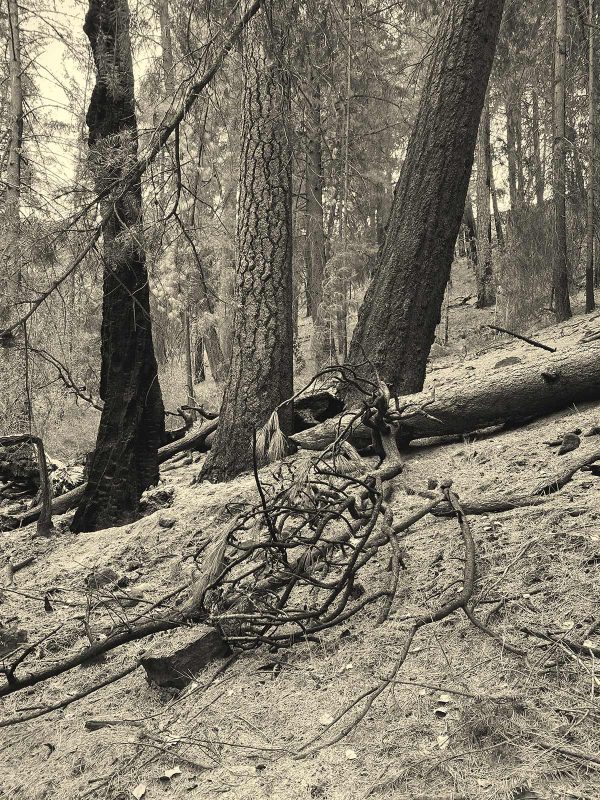

Deluged with other apocalyptic news in September, I had not heard about the Evans Fire, and only stumbled into the site by accident, having taken an unplanned scenic route on a journey east that led to a road called Longmire Lane. The Evans Fire burned over 75 thousand acres in Yakima and Kittitas. My first glimpse of its aftermath came at dusk. Chalk and soot, cast in a pink glow of sunset from the sky. It was a somber and haunting scene. The light was too dim for good pictures without a tripod, and I resolved to return the next day. The pictures from that day have been emotionally challenging. Darkness visible is not easy to live with.

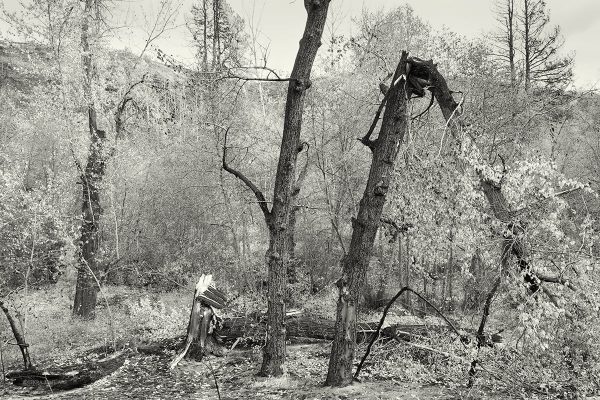

And yet. The landscape was arresting. Each bend in the trail brought a new tableau. Casually beautiful arrangements made by lightning and fire and wind have been staged in the landscape for centuries, unwitnessed or remarked upon except in the language of nature. As I look now through the language and lens of modern photography, I am tempted by color, of course: the sky was blue-gray, the trees were pale salmon and brown and black – yet the sensibilities of another time speak more surely of the emotional space. Elegy, time, the bell jar of the aftermath. I want the spare means of photography in its origins: light hitting glass under a black cloth, the syrup of chemicals and fumes with little room for error, but hand tinting available after as corrective. Or perhaps, the satin washes and dense linework of lithography, color invented by memory. Something that reminds me of Lewis and Clark, and a postcard he might have sent back from the trail.

How do you look at a forest fire? I walked with a friend this morning and we had a tug of war. She wanted hope. I wanted reality. She said we can’t know the future real before it gets here, and any photographer who’s gone into the dark and watched an image emerge under red light would agree. Depending on the paper and the fix, or today’s digital gamma and offset, it could all be a brighter day or an under-exposed night that leaves us barely seeing the outlines. I find solace in staring head-on at what’s in front of me; I don’t trust hope. I’d rather take the soot of the fallen branches and draw on the cave. What’s ahead? Gaugin said “I shut my eyes in order to see,” and that is part of it too: drawing to see, with one’s eyes shut.

These images are part of a new series about The West, which itself is an idea based on unreasonable hope. I will return in the spring and see what has changed in the canyon. Perhaps the next landscapes will be almost entirely green, and then I may have changed my mind entirely on how to look at a forest fire.

Leave a Reply