“The essence of spiritual practice is remembrance, whether it is remembering to come back to the present moment or recalling the truths of impermanence.”

— Andrew Holecek, Tricycle Magazine, Winter 2013

“Don’t talk, I can’t hear myself see.” –Jerry Saltz

I first visited Cloud Mountain 23 years ago for a seven day silent retreat. At that time a year of insomnia and grief in the wake of my father’s death had taken me to the brink of despair. My view of the world had become dangerously distorted, and if I wanted to come back to my life I needed to take my meditation practice to a different level and rewire my brain. This was before the idea of negativity bias had become commonly accepted in science and spiritual practice, and so in the first days of retreat I spent a lot of time beating myself up for my mind’s inexorable turning towards darkness. By the end of the seven days I had turned enough times to face the other direction that I could now see it existed. The searing images that appear in states of absorption may be only seconds in duration, yet they can powerfully and permanently alter the brain. As well, the steady accrual of mindfulness practice.

I will never forget the feeling of my hands on the steering wheel as I prepared to drive away at the end of the retreat. Did I still know how to drive? I tested the the brake pedal and fiddled with the key. I would start slowly. As I rolled down the hill at three miles per hour I realized that my father was still dead, that a particular sadness was permanent and immutable, and that I was okay. My breathing remained comfortable and calm, and my eyelids didn’t prickle. In that week nothing had changed in the facts of life, but my capacity to carry it had changed. I proceeded to drive directly onto a one-way road into a clear-cut. This is how it is: the world doesn’t stop being itself while I’m being quiet.

Over the several decades since, I have become steadily more happy. Terrible things happen, but without the added burden of taking them personally. When I feel grief I feel myself gathered in a very big net with others. I also increasingly live by this truth: “Know that joy is rarer, more difficult and beautiful than sadness.” When I saw this quotation from Andre Gide in the description of Cloud Mountain’s December “Discovering Joy” retreat with Lila Kate Wheeler I signed on. Happiness and joy take vigilance, and continual practice. What follows are my notes from memory and a few photographs, taken after the formal retreat had ended.

Walk, sit. Walk, sit. Do not speak. Pay attention. Walk, sit. Dishes. Sweeping. Sleeping. Do not write. Do not read. Noting, noting. Breathing, tea.

The most startling meditation of all is the experience of social space that occurs when you have chosen not to speak. In mid afternoon eleven people inhabit a room crowded with couches and chairs. Each chair turns at right angles to the other, so that the people sitting in them are at right angles also. The gaze of those facing the window intersects that of the people looking at the fire, the fire gazers must stare through those huddling to get warm, and the wall-gazers may bump into anyone. For distraction we cannot even read the titles of books, as a curtain has been drawn across the library.

In normal life this arrangement could be cause for unease, or even an altercation. The person turned in profile has no defense. The person to their right could be judging them with their eyes, making commentary on the width between nose and chin or cut of clothes — what then? The forced perusal of strangers occurs rarely, in waiting rooms or on trains, and then the savvy have headphones or a book with which to escape. Here most of us have agreed not to look each other in the eyes. To look is a form of speech, and it leads to wondering, and wanting a look back. So we are looking gently, looking without looking. We consider the snow, and the fire, and the profound ease of knowing nobody has to apologize for their silhouette being in the way of the view of a tree — or for any other aspect of their being. We could be illustrating this passage from “Monday” by Billy Collins:

The birds are in their trees,

the toast is in the toaster,

and the poets are at their windows.

They are at their windows

in every section of the tangerine of earth-

the Chinese poets looking up at the moon,

the American poets gazing out

at the pink and blue ribbons of sunrise.

Some of us are preoccupied with the difference between looking out at snow and actually walking in it, which will come at any moment.

Walking meditation.

Not much to it: pay attention, but walk while you do this. Feel your legs, and feet, and the ground, all of which are so cold to do so will take a lot of extra effort. I find a patch of sun on the road that no one else has seen. It seems selfish to take this spot but I convince myself that I am the coldest one of all, the most in need, and stake my territory. I tilt my face to the morning sun.

My eyes half-closed, I see blue amethysts on every snowflake. If I raise my eyelashes slowly they fragment into rainbows, a prism each. Someone slammed a door of beveled glass and it has shattered all around me. My tread is early, the path still white, and on snow my boots sound huge and blunt and bruise the silence. At the edge of the bamboo I turn around and greet my shadow. It is skinny-legged and big-hatted, bundled and funny and twice as tall as me. Who is this, I think, this shape that has the happy grace of an animal or a ten-year-old? The sun warms the back of my legs and my shoulders and leaves my knees and nose to shiver. Creature craving, desire. Only if I walk to my shadow may I turn again and feel the sun on my face. So back and forth I walk, watching my shadow slide along the wall, then turning to greet the sun, dozens of times, until the path beneath my feet wears to gravel.

At some point I see the white summer lawn chair on the dock. Its lap is full of snow, yet it sits at summer’s hopeful angle. The pond wears a thick pelt of fur, reflecting nothing. And it strikes me that a riddle lives here in this moment as my eyes half-shut to the sun that sees me and warms me so fully. My shadow stands behind me, the mirror wears a shroud, and there is no way to make the habitual toast to my image: no reflection, no camera, no wistful rearrangements of features or arguments with the trace of time.

“The sum of the self on two legs equals the square of the frozen lake and the burning sun. Which will melt first?”

This problem is usually worked out with flagpoles and a six foot tall fireman and the noon day sun, wherein the measure of all triangles and how to best use them becomes clear. I’m on my own with it, and I have never been good at story problems. As my mind tightens reflexively I become aware of another shadow at my side, and something moving. A gray shape flits and gathers in a blur of leaves and branches, stutters, and pauses. I trace the shadows to where they end in stalks of bamboo, and move my eyes upward until my gaze levels with a little gray bird. She places her weight on a branch so that the snow-covered leaf is upside down, the apparent best tilt for drinking snow. As she bends to drink I see a cinnabar dot in the center of her head. Backlit, the sun bursts around her on all sides. I shiver with the possibility that this dot of red is a bindi and I am not after all in Southeast Washington, but in Varanasi, by the Ganges.

Which is about when the bell rings to go back inside and cast aside all illusion, saving me from trying to answer a problem that I would rather hold onto: just knowing it’s there, the white distance between the points of a triangle, the luminous sense of possibility, and the bindi bird.

Working meditation

Just do the dishes. Notice how the bowls in the suds clink against each other like bells. Notice resentment at the oatmeal pan, oh most odious thing. Wonder if you should pantomime to your partner that one of the spoons needs to be rewashed, or if this will be insulting, and if perhaps you should just wipe it clean on your apron when his back is turned. Sneak it back into the suds. Fall in love with the gloves, which reach all the way to your elbows. Admire the way your partner, a surgeon, does everything calmly, with economy, as though he has done it hundreds of times. On the third day, under his spell, actually do the dishes.

Wondering

The man sits by the fire and eats an apple as though his life depends upon it. On the second day he disappears, with no note or explanation. I think of David Whyte’s “What to Remember When Waking.” I wish I had thought to break silence and offer these verses.

To be human is to become visible

while carrying what is hidden as a gift to others.

To remember the other world in this world

is to live your true inheritance.

You are not a troubled guest on this earth,

you are not an accident amidst other accidents

you were invited from another and greater night

than the one from which you have just emerged.

— from What to Remember When Waking

But it’s not as though I don’t read often from my own book of consternations. I will never know his story.

Sitting

Nothing fancy, just sit, in a yogic pretzel or a folding chair. Just try to hold your head up off of your lap. Breathe, count, wander, return. The best time, and yes I’ll say one is best, is when sloth and torpor lift and and I can find a thread of concentration. Three of us remain in the room into late evening. This quiet is rich and so comforting and full. Finally, ease. Evening: why was I ever afraid of you?

Often I look up and see the people on their cushions and their chairs and I think, well this is just another version of bowling alone. In many American cities 40% of the people live alone. And they go on retreat and don’t look at each other or talk. At the same time this brings us the communion of silence we are gnawed on by alienation. There is no way to confirm or unconfirm a worry or doubt. Dear Roommate, I am sorry I woke you up rummaging for melatonin at 2 AM and then the four times I got up in my crackling sleeping bag. I wish you had come with me to look at the stars, I’ve never seen them so bright. But I don’t write that note. Instead I try to make amends by folding my clothes neatly rather than throwing them on the bed, and lining up my shoes in a row by the door.

At the end of my first retreat at Cloud Mountain I was so starved for human connection that when it was over I drove to Chehalis and got into a half-hour conversation with a stranger about Betty Crocker Tupperware. She was probably five years from the end of life and I was at the beginning of the middle, but we were equally desperate for warmth. It’s amazing how much conversation two people can make of whether plastic containers should be twist off or lift, transparent or opaque, round or square. Here, in this group, I don’t want to have an encounter group, and I don’t want to chatter. But it does seem that once a day we could gather in silence, eyes closed, and touch shoulders. Monastic tradition is not always the best antidote to a culture that has lost all sense of tribe.

Nature

The pipes break. It has not been this cold here since 1898. The train wails in the valley, and now it doesn’t sound so sweet. A hint of dread snakes into our collective hearts: no tea water. Maybe no food or heat. Maybe they will send us home. A sudden sense of being a tourist, and I think of homeless people on the street and feel the intense privilege of paying to go somewhere and be cold and do the dishes.

People fix things. We’re going to be all right.

Walking

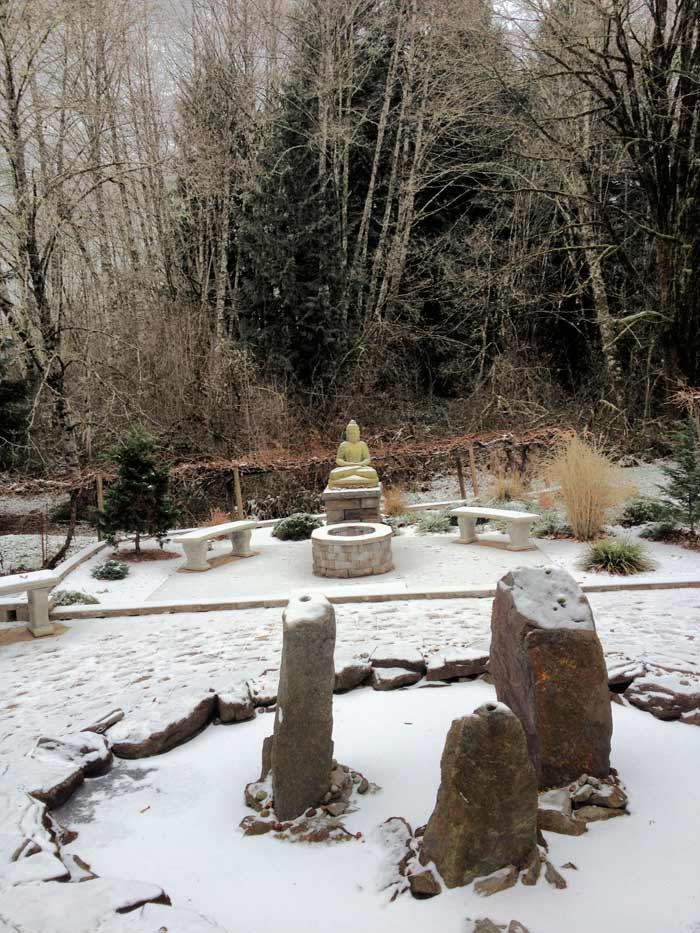

Because of the snow I don’t just see my own footsteps, I see everyone’s. Twice I have come to the maze, I have never seen anyone there. Yet I follow their feet, around and around. I can see them lift, and hold, and turn at the end of each pacing. At the center of this geometry a Buddha sits with shoulders cloaked in snow. I think how it must have been to be The Buddha, and not have a statue of yourself to visualize. Warm skin, flies, tropical heat. Here it’s just me, with my hands in my pockets. Fear of winter lifts a bit.

Talking

We break silence, in a circle. Hilarity, heartbreak, wisdom. Lila is real and revealing of the difficult passages occurring in her own immediate life. We feel free to be ourselves, and no one speaks in that careful spiritual patois that can afflict a Buddhist community. I marvel at the diversity of the group: from early twenties to near-eighties, men and women, people from remote Oregon outback, from Argentina and Mexico. For each of us the path to joy and freedom is unique. Sometimes joy looks like its opposite, but we have learned to wait. I don’t think I will need to go to Chehalis and find a stranger in the grocery store, but I think that I will think I see these people everywhere I go, and even when I realize they are someone else, I hope I will greet them as friends.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

Resources:

To find out more about Lila Kate Wheeler go here.

If you would like to do a retreat, visit Cloud Mountain. Or Spirit Rock.

For the best writing on contemporary Buddhist today, check out Tricycle magazine.

And for some wonderful longer reading:

The Buddha’s Brain, by Rick Hanson

Bowling Alone, by Robert D. Putnam

Hardwiring Happiness, by Rick Hanson

When Things Fall Apart, by Pema Chodron

del webber says

your telling of the steps and process….your sharing of the moments is both sensitive and generous. This is very attractive and moving even to a non-meditating, non-Buddhist. I might even have a little ‘silence envy’.