“Thus we live in a world that first existed inside the heads of others, a world built up through innumerable sustained acts of intentionality, a world where everything speaks not of nature and her processes but of its makers in their resistance to those processes. In a very real sense we can be described as living inside the heads of others, in an excess of interiority that obliterates our own relation to material origins, to biologies, to our bodies. In some way, making was intended to override the givens of nature, to create a world; that world has itself become a given whose terms are more limited in their scope for imagination and act. The world is so thoroughly made it calls for no more making, but for breaching its walls and tracing its processes to their origins. “Taking apart” has become the primary metaphor and “backward” the most significant direction: the creative act becomes an unraveling, recouping the old rather than augmenting the new. ” –Rebecca Solnit

Seattle’s Asian Art Museum sits in a stately Art Deco building nestled among trees in Volunteer Park. Known for its extensive collection of Asian art, SAAM also hosts visiting scholars and exhibits of contemporary Asian artists. The park and the building create an exquisite setting for contemplation. Although as a long-time student of Asian calligraphy I used to go there often, over the years the habit has left me. I think I tell myself everything in the museum is just too old, the artists are dead, and I already know it all. If I’ve seen one brush stroke I’ve seen them all. And if I want a review of Asian art there is Google…..

I can tell myself all kinds of things about museums and deadness and irrelevance. And then one day real death comes to the museum and jolts me out of complacency. Antiquities I took for granted, knowing they would be forever in the cultural vault, are blasted in a few hours into rubble. Human beings are mowed down by zealots who have captured eternal instant replay on television while the art itself, and the sacrificed human beings, vanish. This must be in the back of my mind when I make a turn into the park one evening with no forethought or planning or any special reason at all. I am on my way somewhere, I have something important to do, but instead I stand in the twilight above the reservoir in front of the museum and breathe deeply the air of the day before spring. Plum blossoms fall into the little pond that had two swans when I was a child. The door to the museum is open and the graceful Art Deco windows fill with amber light.

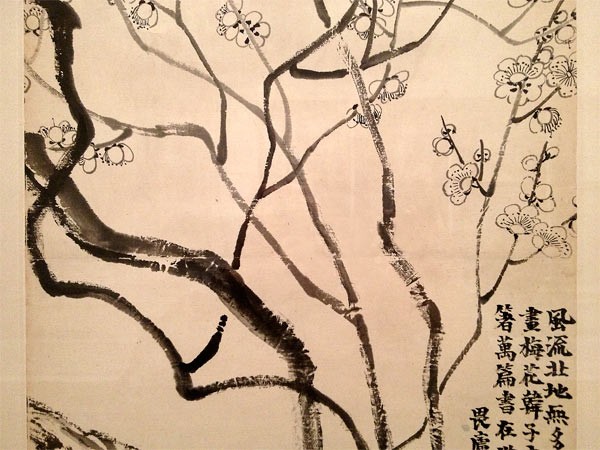

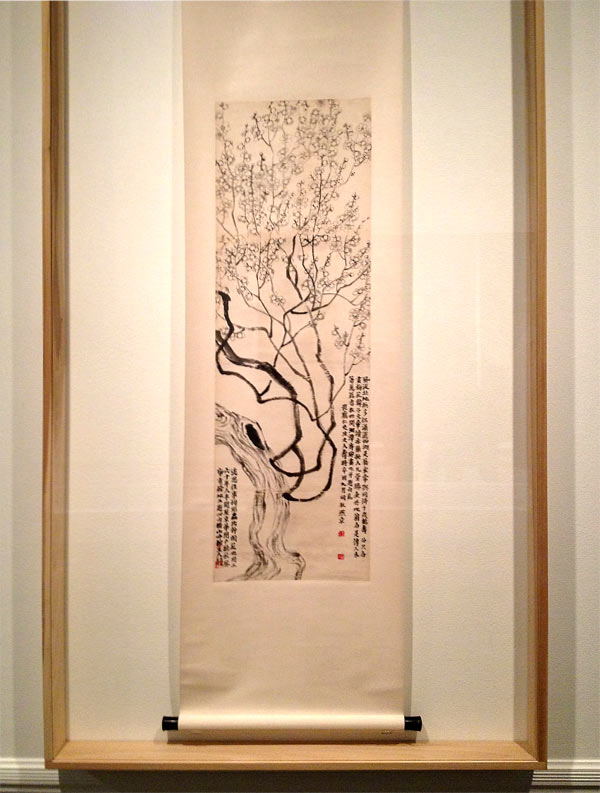

Inside I can turn right to see Mr.’s Japanese hyper-now pink and neon Neo-Pop or go left and backward in time. I turn left and realize immediately that I know nothing, that I have never seen anything here before and that every brush stroke is a new event. It is a Thursday evening, and only a handful people are in the museum. The quiet is luxurious. I can take as long as I want to to stare at small things. Like how the paper on this long scroll of plum blossoms by Qi Baishi is done in pieces and glued together, in a set of ascending stutters and near-misses as the brush stroke continues from one sheet to the next:

Rice paper shrinks and expands on contact with ink. It is a formidable challenge to push and pull a brush to the sky, stopping and starting at the edge of each branch in just the way a tree grows so that the plum itself is not offended by the effort.

This piece alone changes my heart rate. I have stepped one layer back in time.

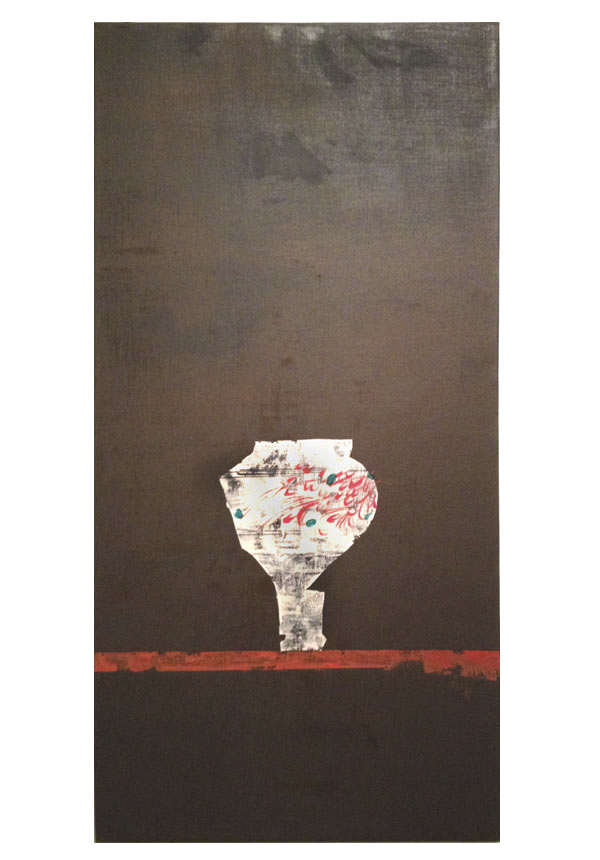

The exhibit is called “Conceal Reveal: Making Meaning in Chinese Art, ” and old is mixed with new. I stop in front of this painting by contemporary Chinese artist Wang Huaiqing:

“Here the artist plays with layers of symbolic meanings by setting a meiping vase upside down on a red table, alluding to the overturning of the past as well as expressing the auspicious message that peace has arrived. In Chinese, the word “vase” (ping) is a homophone with the word for “peace,” and the word for “table” (an) is a word that means stability and harmony.By turning the vase on its head, Wang alludes to the Chines word for upside-down, (dao), a homophone for “ to arrive.”

In other words a reminder that the past was not a bowl of cherries and people have been beheading and invading and cultural revolutionizing since the beginning of time. If we upend the vase and start over is it more or less peaceful? Ask the man who wrote The Better Angels of Our Nature. He seems to think we are on an upswing and that human beings are becoming less violent with the passage of time. We are conversing more and peaceably exchanging world views.

And standing up for our better natures. Or at least trying.

I would like to dress in a nine dragon summer robe, and sleep on a pillow made of white earth, where the dreams arrive carrying love notes on trays and the lotus always rises from the mud by noon. I would like to be an Arhat and inspire the sculptor who built this face of hemp and lacquer, layer after layer laid over wood or clay.

I emerge from history to more history, the skylit central courtyard ringed with Indian statuary, the space making me dizzy with its height and purely secular, graceful beauty. Through the doorway I can glimpse Mr’s nightmarish vision of adolescent school girls and Fukishima, tiny televisions and random detritus spilled into a towering installation in the south wing. Another time, for that. I am full and at peace, and grateful. Maybe contemporary art is supposed to disturb me, unravel my paradigm and make me fret even more than I usually do, but for now I’ll take refuge in what remains of tradition, and in institutions devoted to preserving culture and civilization. For an hour or so I will turn my face up and live in museum light.

The quotation from Rebecca Solnit it courtesy of a wonderful talk given by artist Michael Cherney at the Seattle Asian Art Museum the following weekend as part of Asia Week. Do take a look at his work, it is phenomenal. All images above were photographed at the current exhibit at the Seattle Asian Art Museum.

Leave a Reply