There is a perfume called Museum, available at discreet boutiques. When you daub it behind your ears pearls attach, shimmering and pendant from tiny diamonds. Your neck grows long and swans into the darkness of evening above a silk dress sewn from the sky of early dusk. Every word spoken, from the mouth delicately suspended above the long white neck, has the quality of pronouncement. What your eyes light upon is anointed, pedigreed, and placed on a pedestal. This girl with the pearl is the ultimate docent. She has ridden alongside the robber barons and hauled the world’s worth home, there to catalog objects that always aspired (without knowing it!) to become artifact. She finds it charming to be confused with the girl in the Vermeer, the girl hanging in the Louvre and adored by millions.

Because of the internet, which appears in the palm of my hand every five minutes, I cannot help but compare myself to that Girl. Behind my ears is simply the after-scent of shampoo from Walgreens. I wear jeans and a puffy jacket, and sterling silver ornaments, buried in unstyled hair. If I was to de-acquisition a chunk of statuary and remove it from its pedestal for my personal collection I would be hauled off to jail and my friends would leave me. Nothing says have and have-not like a museum.

The Seattle Asian Art Museum tries to meet this situation head on, so to speak, while being appropriately oblique. In the Room of the Beheaded Buddhas, each head of the half-dozen is clearly displayed as a trophy. The only thing missing is the bloodied chisel. Says the placard: These fragments of figures also reflect the difficult reality that the historical art market supplied such small, portable and alluring objects to collectors under the circumstances of colonial expansion and other forms of cultural imperialism. Explore our smartphone tour for further discussion. Should you flinch at the phrase “cultural imperialism,” remember that the museum is not running for higher office. It is simply telling it like it is.

We see so many floating Buddha heads these days we may have forgotten that they used to belong to bodies. The garden magazine awards have stairways adorned with them, the Hell’s Angel has one welded to his fender, and your neighbor’s picnic table holds a head facing the eastern sun, surrounded by rocks and snailshells. Nothing says higher consciousness like a stone man with long ears, refusing to meet our gaze.

The row of heads in vitrines is deeply unsettling. I have been coming to the museum for many years, and I have treasured the moments of coming across a particular sculpture, the HEAD OF A LOHAN (ARHAT), Liao-Chin Dynasties, China, 10th – 13th century. Dry lacquer. H. 26.7cm. (10 1/2 inches). He was always alone, “without context” and partly by virtue of that, because of his lack of companions, I felt like he was someone I could sit with for a while. He did not look highly stylized, not like someone who had figured it all out and was there to teach, but like a pilgrim. Now he stars as the first in the lineup of colonialist scalps and our relationship is over. I should not have been surprised. We live in an age of supreme disembodiment. Our parts are critiqued, found wanting, and sold back to us with fewer wrinkles, stronger muscles, more Paleo authenticity. Why not do the same to the avatars?

I was relieved to walk away from the room of parts and step into the darkness of the Gallery of Awakened Ones. Here a black ceiling and dramatic lighting create the sense of being in a cave. Some of the life-sized figures are missing their hands, but they at least have something of their bodies, and can breathe. It feels, in this room, like the museum has surrendered the obsession with artifact to the experience of contemplation, and it is a transformative experience.

I don’t think I have ever given conscious thought to the effect of scale in a museum. Moving from the room of disembodied to embodied jolted me into thinking about all the ways our own height mediates experience. The first time I went to the museum I was three feet tall, and my father took me there and lifted me up and set me on one stone camel while I like to think my mother was sitting on the other, facing me, though that is doubtful. By that year the family unit was fragmenting; it is more likely my father took me there alone to spite my mother by giving me culture behind her back. (Little did I know then that the camels were originally part of a “spirit way” leading to a tomb.) Later, when I was three feet eight inches (a door jam documented these things, in carpenters’ pencil), my father took me to see the snuff bottles. At this height I was eye-level with the pearly dragonfly caught in smoke. My father explained to me how they were painted from within. In my mind the painters were tiny people, tiny as ants, wielding brushes like brooms with one straw.

I have few criticisms of the new museum, but the fate of the snuff bottle collection is one of them. Is it just childish nostalgia that begs to know the collection would always be there, static, immoveable on its wall of glass shelves? How many years of my life did I visit the collection, in how many various states of Pacific Northwest melancholy? Perhaps someone at some point traded out the Rising Phoenix for the Two Fish and Lotus Leaves, but in my mind they were a fact, an arrangement of aesthetic logic as certain as the temperature of the ice caps. Now the snuff bottles are scattered here and there, and some are posed, most alarmingly, in a vitrine with modern wrist watches. If the watches were not painted from the inside with broom straw I frankly don’t want to see them here. Please, curators, get back to me and tell me: by what disruptive logic you did this?

The room of tiny snuff bottles originally faced onto the park. That is where, at nearly adult height, I learned to skip through sprinklers instead of sleeping through continuous progress algebra. Outside the walls of the museum the lawns rolled out in great velvet swaths, encircling sequoias and cedars that formed, in their dark skirts, giant private rooms. Here the 8th and 9th graders drank whiskey and beer and smoked whatever they could get their hands on. We could lean back in the tree rooms and look up at the clouds floating across the windows of the museum: it was our backyard, and we thought we owned it. In the afternoons my best friend and I would lie beneath the ancient maple on the western lawn and stare at the sun through the leaves as they moved in the wind. One day she said to me, “unpatterned patterns,” a phrase that has served as a numinous gem of ‘60’s wisdom throughout the rest of my life.

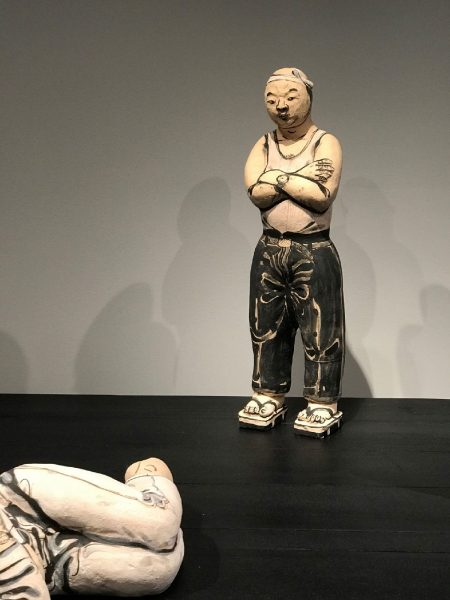

It was this phrase that came to mind as I stood in the new east wing of the museum cantilevered out into the park of my childhood. The use of space in the Garden Court is recklessly wasteful if the goal is to exhibit more of the museum’s collections. In a long nearly empty rectangle a handful of vitrines stand before the soaring windows. On each pedestal is only one ceramic piece. The effect of this minimalism is quietly dazzling. All the contemplative power of the art within the museum’s dark cloisters now spills into the light, where nature and “artful artlessness,” the unpatterned patterns of decorative traditions, ornament the simplest of shapes. A vase swirling with new leaves faces a winter tree. Trees and sky reflect into the galleries and onto the glass in front of the artworks, merging outside and inside, outsider and insider. One can lean against the museum wall and imagine, framed in the windows’ floor to ceiling divisions, a Chinese landscape from the Song Dynasty.

The true value of art depends on an intangible aesthetic return, which varies with the knowledge and taste of each beholder,” –Dr. Eugene Fuller, founder of the Seattle Art Museum.

How daunting to be a museum curator, attempting to corral audience and shape its point of view. No amount of podcasts or labels orchestrated to describe time and causal relations can stand up to the anarchy of individual subjective experience.

Audiences do not behave.

I feel queasy as I allow the word “stoned” into my public memory of the museum and its park. We are a city in the midst of an addiction epidemic. How flippant, how shallow, to mention those days of teenage miscreance as though they could have any bearing on what the museum so studiously, with archival reverence, holds inside. Yet any timeline of Seattle cannot ignore the importance of Volunteer Park, and of the psychedelic ‘60’s, in the history of the city’s consciousness revolution. Volunteer Park was the site of Seattle’s first large Be-Ins. It is where I first heard Laurie Anderson play her violin, in an era when you could go to the Deluxe Tavern after, and have a star-struck daquiri with her. It is where world music tribes found each other, mixing Indian tabla with steel drum and anointing the anointed with jujubes, (which, if you just press hard enough in a warm western-sun moment, will stick to your forehead unassisted.) It is where countless underage girls found 20-something hipster boyfriends who took them on the back of motorcycles to communes. Where the disaffected found affection and the alienated found allegiance and everything was really fine.

Inside the museum we see the art of sages fueled by moments on high mountains and lesser sages fueled by saki seeking to put the plum blossom into the canon of higher beings. Yes, a wing of the museum is devoted to – (in modern PC parlance “decadent” and “classist”) – arts of the “Material World” – but in Asian art the material and the evanescent stand right next to each other, with a vocabulary that can seem indistinguishable.

I think again to the hard reflective fact of vitrines, how precious things must be enclosed to protect them, and how this vital barrier creates both a class division and an opportunity to see time and own the historical timeline of culture differently. When we look at an object encased in plexiglass we see through this cube to the next cube. Overlaid across gold leaf dragon flames and lacquered bamboo is the fleeting reflection of a woman’s faux leather handbag and a man holding up his phone. In the polished barricades of the vitrines present and past refract in a constant uncontrollable cinema that creates its own timeline.

So often we are encouraged to see time as a “time-line” as though you could divide it equidistantly with a sharp stick of charcoal on some wall with a beginning and an end. Ha. When I look at that wall I see it meandering pretty much forever, which puts you at some point stepping backwards into the Seine, (or some other stand-in for The River of Time) – and pretty much drowning. Time doesn’t work that way: it’s not linear. The stoners and the sages knew that time past and present are a fiction, that they are in fact uncountable layers of now. That is how you can bear to become a master of kintsugi, which takes ten years. You know that the time it takes to master the arts of antiquity is a kind of bendable present.

The moon’s sense of time is carefully charted, and so I know that when I went to the opening of the museum I was not imagining that the moon was full. It was full, and that particular kind of moon is called “Snow Moon” because in February it can coincide with drifts of snow over crocus. I left the museum calmed by the sense of deep reflection it offers. Somewhere in the museum’s many rooms, perhaps the room called “What is Precious?” or “Writing Images, Painting Poems,” I had had a conversation with a stranger. We both had stopped, stock still, in front of a particular piece from the 1630’s. He was half my age or less, perhaps Persian, and we locked eyes across the chalky cracked paper of the royal decree from Shah Jahan to his son.

“His father built the Taj Majal,” the young man said. “He was asking his son to report on the war.”

“Nothing changes, right? But oh my god the signature!” and we had a long moment of silence, admiring the fact of this man writing to his son, in calligraphy so vivid and beautiful and real you could smell the ink.

On the way to my car I looked up into the bare branches of the chestnut trees by the water tower and stalked the beauty of the moon for quite awhile. It resisted me, always blurry and far too bright. Details disappeared. Just the light was left, there under the water tower. Perhaps that luminance is the enduring gift of the museum.

Leave a Reply