“Keeping vigil over the longest days of the year, in the month of the white flower.”

With only three days left before the turning of the equinox I find myself unable to go inside. I want to hold on to every minute, memorize the evening sky, and tend the garden meticulously. Last night I thinned the bamboo until the last faint glow had left the clouds and I could hear the raccoons rustling. Then amidst the pale constellations of anemone and allium I sat on the stairs and reveled in the warm and unexpected air. At dawn I returned to the same step and listened to the birds. Intermingled with the grown-up towhee and the bullying crow I could hear the unmistakable high pitched keening of baby chickadees. These are remarkable days. Days when time stretches and the night and the morning seem to recognize and greet each other, clasping hands across the dream hours.

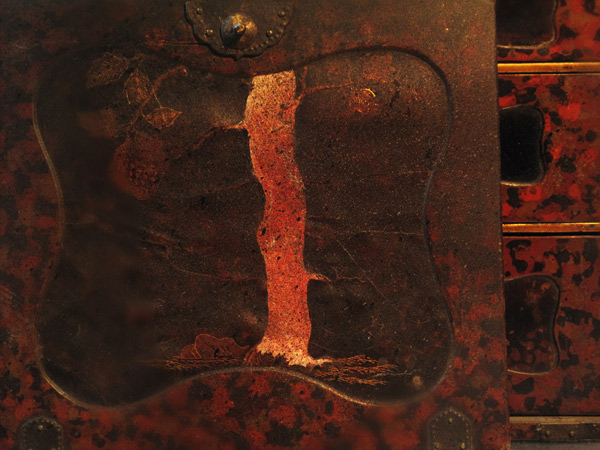

It is very easy to dream with ones’ eyes open and to miss what is sitting right in plain view. This week while sitting and writing I looked up and suddenly saw the lacquer box. When I stumbled upon it years ago in an antique store I knew it was something I had to have, an object of instant charisma and absurd expense that became, perversely, annoying on possession. The cover would not latch, and the surface seemed very fragile, almost ash-like, flaking when exposed to sun. I stopped looking at it directly, with a combination of guilt at my acquisitiveness, and chagrin that I could not take care of this old and precious thing which seemed to be losing beauty with every day in my possession.

The mystery of why and when we decide to see what is in front of us has never been explained to me. Perhaps in this case the proximity of dawn to midnight jarred me from my usual sleep, and I rose and picked up the box. From across the room the panel covering the drawers seemed to show simple primitive shapes, perhaps a palm tree, or a hut. Only as I held it in my lap did I see that it was meticulously drawn, each shape outlined, incised, and precisely inlaid with gold. It could be “merely” painted, but part of the miracle of this object was its flawless subterfuge. When I ran my fingers across the surface I could feel no raised edges as I would with purely surface brush strokes, but something more complex, an incision and an addition. Over this, layers of lacquer and a dusting of time and its furrows. If I was being fooled, if it was in fact “merely painted” then all the more power to the artist for leaving me dazzled, either way.

Not only had I not really studied the technique, I had missed the narrative; not just one tree but two: a banana tree, a pine, intertwined. A man in scholar’s robes and cap sets forth from his house, holding a brush at eye-level as though to take the measure of all that lies before him. Through the open shoji screens behind him incense burns, arranged in graceful order with a red teapot, a large urn and a slender vase with two fronds of grass. Several paces behind, a child or servant follows his master, ink stone in hand. I can hear the crickets; the air is damp.

On the back of the door, all studies fail. The shape I would have told you was a waterfall rises from a cloud on the ground: not water but a tree raked by moonlight. Its fruit is outlandish and skewed, unidentifiable except for a multitude of red seeds painted in thick, lustful carmine. Perhaps this is the tamarind tree, from which lacquer is made. The sense of incense and tropical air is so strong I feel disoriented in time and place, and reach up to touch my hair, half expecting it to be long and lacquer-black, roped in pearls and ivory combs. I remove the door and open the drawers. The first one, cobwebs, the third one, nothing. But the one in the center holds an old postcard, and the dried pod of a Japanese Snowbell. Oh, that spring! When did I hide this memory from myself? And why? I hold the perfect brown bell between my fingers and marvel at its perfection. If I squint I can see the tree and it layered temple of branches. Was I with a friend? On a solitary walk? Perhaps it does not matter that the details elude, because in this moment I am completely here, in this practice of forgetting and remembering, again and again.

Photographs © Iskra Johnson