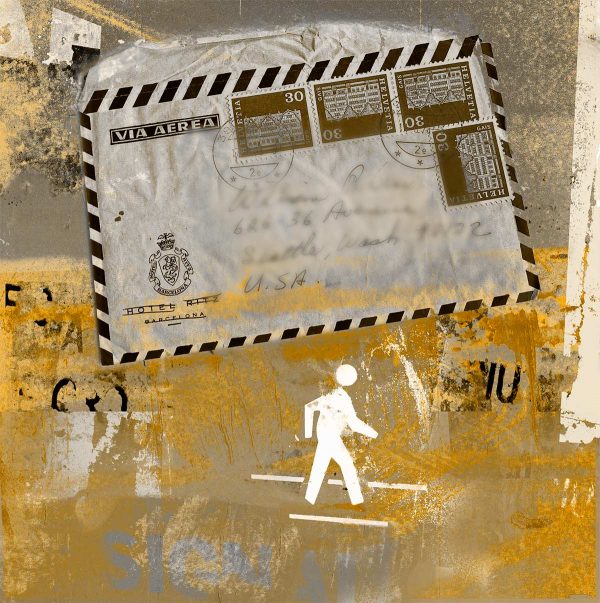

The Correspondent, ©Iskra Johnson

(This late summer dispatch breaks all the rules of “newsletter.” August is a time of slow thinking and revision, thought and word pasted and lifted and re-placed in an order based on considerate disorder and association, ie. on the structure of my mind. If there is no news (I have been immersed in art history which is by definition old news) there is still, however a “letter.” This post is about letter writing itself, and how personal correspondence can mean the world and re-make the world of our creative lives. Settle into a deep chair, with good light or a rustling tree and a cat at your feet. Consider that the post office would love it if you bought some stamps.)

On this particular morning, about 214 days since the pandemic became the official organizing principle, I am sitting at my kitchen table drinking Earl Grey and looking at a stack of books and magazines and letters accumulated since spring. In April my friend Jennifer began sending me her monthly Poetry subscriptions along with pages torn from magazines. Every page is pre-read and annotated with trenchant scribbles in the margins, curated personally just for me. Jennifer has reached the place in life of casting off. I am still bringing things into my house, desperate for distraction, but seem to have confused doom scrolling and pulp novels with The Great Books. I gather romances from the Little Free Libraries on my walks and have not made it beyond chapter 1.

When the first poetry letter arrived I was ecstatic. Mail! Brown paper and string! And delivered by a man in blue socks and shorts, as though it was 1958, a sandwich meant Mayonnaise on Wonder Bread, and Lassie the Collie still roamed the earth in his white socks, teaching us what heroes look like. The letters have ignited a connection that feels bigger than just the two of us, my friend and me sitting alone dangling face masks on our wrists in our separate homes. Over 20 years we have corresponded by email and post, with a dedication that is Victorian. When we compose a sentence to send to each other it is with the knowledge that we are writing, not just the tourist postcard’s “wish you were here,” but miniature novellas painting scenes or memories that cross space and time. We write to bring each other actually here, and we take great care.

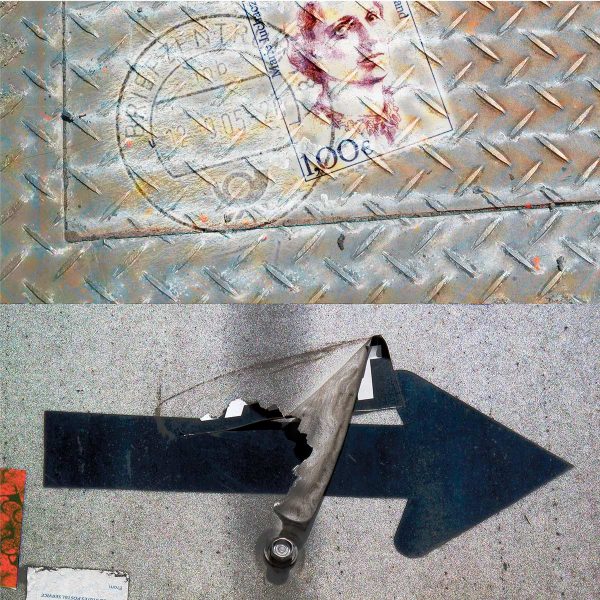

Special Delivery, ©Iskra Johnson

On top of the magazines gathered today sits a clipping from Harpers headlined “Where We Live Now, America’s Poets of Place.” The poet Jana Prikryl writes of New York:

“In this city friendship’s / the main mode of disaster prep.”

Written two months before the beginning of the pandemic, the line is prescient. Our new place, for those in quarantine and lockdown, is one of narrowing proximity: our yards, bedrooms, cars, and our memories of places we have been or once planned to go. The future itself has now become a memory. What can get us through this narrowing of place and hopes for the future is the friendships tended over time or forged anew in duress. Or unexpectedly, perhaps fleetingly, with a person of shared solitudes walking down the street. With that person, who might become a future friend, we share for a brief glimpse of one of God’s Best Skies.

(If you are spiritual but not religious, or just an old fashioned atheist, I’m sorry….)

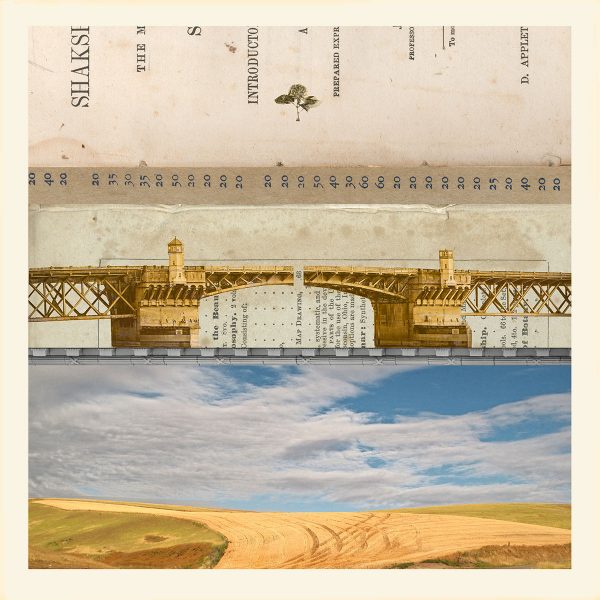

My correspondent is a poet and painter born between the Depression and World War II. A world traveler who spent years in the Peace Corps, her life has been filled with adventure, risk and remarkable achievements. A free spirited Bohemian by nature, she grew up in a small Eastern Washington town surrounded by tradition, faith, family, and farmland stretching to the horizon. She possesses the almost pre-historic and rigorous intelligence that learned things by memory, and can, as the moment requires, recite Yeats or Shakespeare’s sonnets or sing mass in latin, each passage perfectly attuned. Whether carving a pumpkin while dressed in a rhinestone bustier, or frying lumpia, or painting the Palouse from the back of a truck, some part of her reflexively scans the limitless bookshelf of her mind. I am awed when she looks up and delivers the moment’s consummate inscription, casually recited from memory.

In March, to add punishment to pandemic, the Department of Transportation announced the West Seattle Bridge was broken. In a sprawling city interspersed with large bodies of water and inconvenient rivers the essential arc between west and east was declared impassable, stranding those who live on the west to look at the setting sun for the rest of their life with only their immediate neighbors as company. Jennifer lives in that piece of land across the bridge now properly considered an island.

In this new geography to visit by car and turn island into isthmus requires a detour through fierce traffic and trucking corridors with exits that spin off into industrial wilderness. For me a combination of vertigo and fear of bridges makes a trip across the Duwamish river equivalent to crossing the Styx. I have had dreams for years of being caught between the ramparts of a rising bridge. Long after waking I can feel the hot metal grilles in my fingers, and the gears that make it rise and close shudder through my spine as I hang in space. Every time I get to the entry of the West Seattle Bridge, panic descends, and I turn right on Spokane to drive under it, taking the slightly less terrifying little bridge beneath. That bridge now also has troubling cracks and carries only ambulances and busses; missions of friendship are considered non-essential.

As I look today at the books randomly stacked, each one opened flat as a horizon and ragged magazine clippings tucked between, I can’t help but think of the bridge itself as a torn page, the inscription started on one side and finished on the other, only visible if I run up the rampart and peer over the edge. I am living in collage life, watching as everything comes apart at the seams, is shredded, abraded, torn and cut, and thrown up in the air with no certainty of how it will reassemble on the ground.

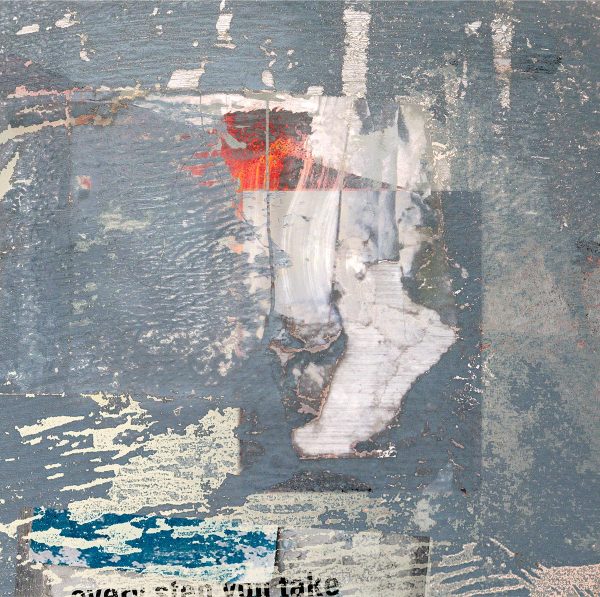

Every Step, ©Iskra Johnson

For years I have kept a postcard of a collage I thought was by Kurt Schwitters on my desk. Today I realized it had almost entirely faded from recognition. Named, dispassionately, “Untitled”, it is an elegant topography of stained papers folded and pressed against each others’ borders. The fragments live in harmony like friendly nation states, the lower quadrant overlaid with misplaced passport numbers. I turned the card over and found that the artist was Robert Nickle, with this caption :

“For me each collage becomes from its beginning a separate evolving world, one that is by its nature constantly challenging and demanding consideration, able to instantly and unexpectedly shift back and forth from a thing being led to a thing that leads. The infinity of each of these worlds is always both my delight and frustration.”

This case of mistaken identity sent me to the internets for research, which lasted unexpectedly for days as I followed one trail after another in a deep dive into the history of collage. I began to fall in love with my own private harem of famous men, some long ago loves, some new: Picasso, Braque, Rauschenberg, Alberto Burri, Romare Bearden, Kurt Schwitters, Max Ernst, Joseph Cornell, Jacques Villeglé, Gwynther Irwin – and hardly a woman among them who was not just a footnote in an entry about Surrealism or Dada, – oh, Hannah Höch where is your billboard?

I have never taken personally as victimhood the obscurity of women artists, but the growing list of men, and womens’ attendant absence from it, gave me a long moment of pause. I don’t think of what I do as “collage,” and I generally avoid the word. Yet I have been working in photographic mixed media, otherwise known as “photo collage” for over 10 years. What was it about a word originally derived from “glue” (from the Tate on History of Collage: papier collé (from the French word coller, meaning “to glue”) that seemed suspect?

I entered “collage” in the Cambridge dictionary and it led me to the smart thesaurus of “related words” presented as a swarm of hyper-linked words almost entirely devoted to the world of craft. A partial list:

artsycrafty, artificer, basketwork, crochet, decoupage, flower arranging, gluegun, handiwork, macramé, modeling clay, mosaic, papier mache, patchwork, pastiche, weaving (and strangely: Taxidermy)

Many of these words are not said in the world of fine art without a curled lip. Many are associated with women: women dabbling, entertaining their children, beautifying the home one hanging planter or shellacked coffee table at a time. My training in the feminine arts began with potholder kits and ended with ashtrays. On weekends Women Act for Peace, or WAP, gathered at our house to press sheets of mosaic into heavy brass squares, using a beige paste glue so pungent it could melt a child’s nose. In the air the smoke of Viceroys and Lucky Strike accompanied the rasp of motherly coughs, presaging the eventual demotion of ashtrays, (“urns”) from the list of crafts acceptable for fundraising.

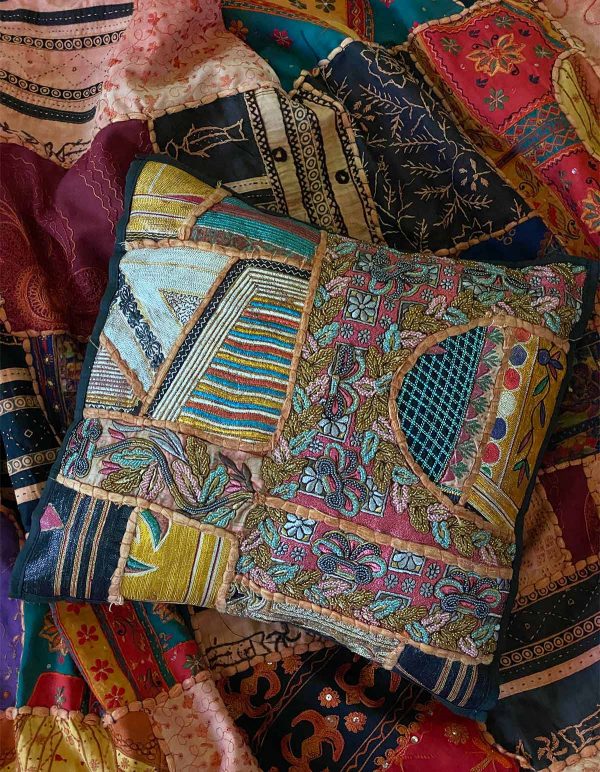

Much of the stigma of traditionally feminine arts has come not from their lethality but from their use of ready made or found pieces, and of pre-made templates that substitute imitation for the act of original design. A quilter doesn’t paint original chintz on each piece; rather the art of the craft is in finding and sorting and deciding which pattern complements the next. It’s the mastery of juxtaposition that makes one quilt rise above the others thrown on a bed. Juxtaposition is the heart of all collage.

Wedding dresses reconfigured as pillow and patchwork quilt from India

My first exposure to fabric as an artform came from the woman who taught art in the alternative school I attended when I was 16. Educated at Yale with Joseph Albers, everything Diana created had both a human warmth and the rigor of underlying design. I would sit at her side and watch as she gathered pieces of worn silk and brocade and assembled them into elegant landscapes. Each piece was anchored to the rest with tiny stitches. Over selected pieces of patterned cloth she overlaid embroidery, the layers of filigree intuitively complementing and making completely new what would have looked to most eyes already complete. The grace and harmony of these pieces radiated out into her home. Vintage carpets covered the floors, books lined every wall, and in the kitchen lived a timeless tableau of fruit and bread on a round oak table, illuminated in a halo of light by the blue enamel lamp hanging above. Behind the table French windows opened to the garden and a riot of flowers and raspberries. To enter Diana’s world was to walk into a Matisse postcard, and you always hoped she would ask you to stay for tea.

I had not thought of Diana’s house for many years. The images arose while I watered the garden, trying to absorb three days of studies and turning the pages of art history books in my mind. I remembered the sun on the roof of her garage, where a blue chair sat in the early autumn light, surrounded by planters filled with tomatoes and cascading nasturtiums. One day I was with her and she looked out the window and simply said, “the blue chair,” and sighed with a deep sense of reverie. In that one moment she condensed a year with Joseph Albers, and taught me everything I needed to know about beauty for the next decade.

As I passed the hose back and forth over the the windflowers I was also thinking about glue, and the nervous chatter in the background when I think about “collage” as an art form. I was surprised and a little embarrassed to find within myself an embedded distaste of anything that might be disparaged as “feminine” or “women’s work.” This judgement sat right alongside the fact of that list of 19 famous men in collage, all of whom seemed to have glued something, likely something they didn’t entirely make themselves, onto something else. And they somehow turned that lazy homemaker’s trick of appropriating patterns and readymades into a “piece of work”– that they and everybody else called “art.”

Pandemic time is slow time, and I spent several days writing nothing, making slow needlepoint stitches through that thought.

Bird, ©Iskra Johnson

Pinterest: Curation and Appropriation

Curation and context are the key. In my days of research I had spent at least half of my time being detoured by Pinterest. Enter any artist’s name in a search bar and the first or second entry is likely to send you to this platform, perhaps today’s most popular form of collage, if you define collage as a bunch of things possibly related stuck to a board, ie. juxtaposed. 93% of pins are made by women. They hunt and gather from the vast sewing basket of the internet and put the things in categories of things that look like other things and that they for some reason love.

And then those things proliferate, replicating dozens and then hundreds of times, often stripped of attribution, entering the stream of post-modern visual wallpaper known as Image Search. Soon you can find yourself completely derailed as you go from looking at the first combinations of typography with paint by Braque to what seem to be millions of look-alikes. You can buy “Magritte” revisited: ten thousand variations of a hat and a cloud and a faceless man not knowing how he got such a high Google ranking for $50 as “wall art.” You can also buy buckets of lace doily stickers (without touching a crochet hook) and dead peoples’ love letters and buttons and lovely stamps, and then, by downloading the right tutorials on glue and sepia glaze you can learn to make scrapbooks with the vintage scrapbook look, just add your own children in a printable cameo, free gift included with registration.

“I have gathered a posy of other men’s flowers, and nothing but the thread that binds them is mine own.–Montaigne

Collage has always been associated with appropriation, but as Maria Popova, one of today’s great cultural collagists, points out in her essay on Curation:

“What makes Montaigne’s meditation so incisive — and such an urgently necessary fine-tuning of how we think of “curation” today — is precisely the emphasis on the thread. This assemblage of existing ideas, he argues, is nothing without the critical thinking of the assembler — the essential faculty examining those ideas to sieve the meaningful from the meaningless, assimilating them into one’s existing system of knowledge, and metabolizing them to nurture a richer understanding of the world.”

Pinterest defeats the richer understanding. It is a replication machine on steroids, and it may be that the constant interference of visual life by this platform has had an outsized effect on my associations with the idea of collage. I don’t recall Braque giving workshops on how to make a cubist pillow covering, but every kind of art that once was invented for purposes of invention is available as a kit or a class. Much of what is available is, of course free as visual information, and the gifting is inherent in the internet economy.

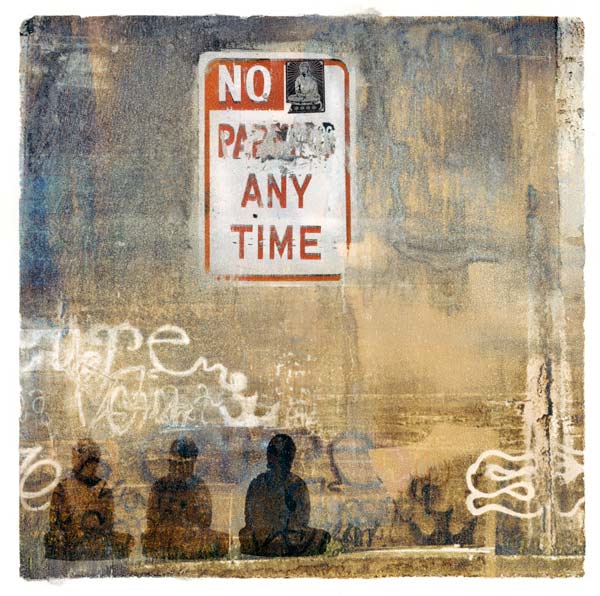

Banksy Was Not Here (or, Steal This Buddha) ©Iskra Johnson

Much has been written about the reset of the art world that is happening during this time. How there could be a return to meaning and accessibility and away from culture as a commodity bet. We may go back to art as a form of letter writing, a way of making connections with those we love and who inspire us. Perhaps one of the sweetest and surprising examples of this comes from a story of the meeting between Rauschenberg and the Italian painter Aberto Burri.

“I went to Burri’s studio on Via Margutta and found him to be very enthusiastic and hospitable. A few weeks later I heard that he was sick. This was the period when I was working on the “Feticci” (fetishes) and then I believed that they had magic powers, so I came back to the studio and made one for Burri with the intention of helping him recover. Two weeks later he came to my house with a little painting, perhaps the smallest work he had ever done, as a gift and an exchange for my “Feticcio”. This painting is still one of my most precious possessions” (R. Rauschenberg in A. Bonito Oliva, Enciclopedia della parola. Dialoghi d’artista. 1968 – 2008, Milano 2008).

***

After I read this story it occurred to me, urgently, that I really had to get on a bus to West Seattle. So last Sunday I put on my mask and braved the crossing of the little bridge to Jennifer’s house. There are many ways to calculate risk. Jennifer and I decided the danger of a visit was less than the risk of never seeing each other again in a pandemic of uncertain duration. It was hot, almost 90 degrees, and our plans for walking fell aside as we limply surrendered to the heat. We ate a little picnic lunch and talked in slow meanders, little of which I recall.

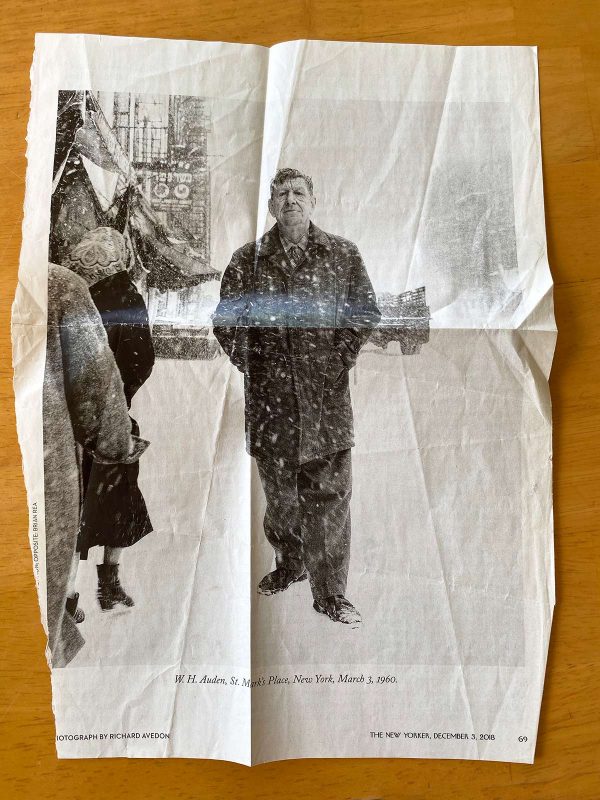

I do remember the stacks of books, and the way she unfolded W.H. Auden and smoothed him out onto the table. “I’m getting back to him,” she said, as though he was an old friend. Later we went to the café where each week Jennifer creates flower arrangements from her garden. I watched as she absently clipped and arranged the tired blooms and transformed, in the last 30 seconds of her efforts, what had been a clump of wilting and uncongenial species into striking harmony. The final touch was a spray of cilantro flowers gone to seed. I would never think to put dark sepia with pink and lemon; watching Jennifer arrange flowers was, like the blue chair of an earlier time, a momentary master class in observation.

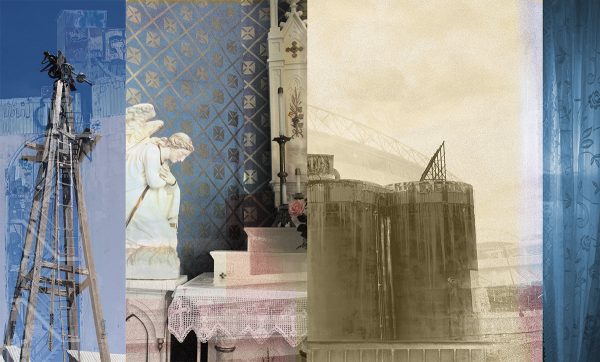

States of Mind, ©Iskra Johnson

The Return

As the bus home crests the top of the Harbor Island bridge I can see the Duwamish glittering, framed by the concrete pillars of the silent freeway. Beyond the maze of cranes and barges the river twists and turns east up into the foothills where it changes its name to “The Green” and where I collected periwinkles as a child. Keep going, across the Cascade Mountains and across the Eastern plains, almost to Idaho, and I can push open the door to the Holy Rosary Church in Pomeroy where Jennifer sat in her smock so long ago, learning to memorize. I am reminded of our road trip across Washington one year, to tend goats and perfume our hair with sage.

Through smeared glass and fluorescent reflections the Palouse lays its ribbons along the edge of the freeway. The tires lined up on the tugboat become horseshoes nailed to a barn. Roses painted on skulls, rusting combines, rusting barges, the same flag above the wheat field or Ash Grove Cement. I instinctively raise my camera to take a dozen blurry shots of horizon and concrete. My quilting basket has 32,546 scraps of the world cropped once in the moment of seeing, waiting to be cropped again in retrospect, sliced and reconfigured into a new potlatch in which the past gives to the present and the past gives it back, with fingerprints and notes in the margins.

Collage life. Everything is always in pieces, a glimpse flashing in a doorway followed by another. There are long moments when everything remains in flux, page after page, sentences, memories, some unfolded, others hidden away. The art of collage requires a final piece of tape, the glue of decision. Why had I ever hesitated to name it? Coller: to affix, adhere, tape, connect, anchor, glue—with all of glue’s messiness and inconvenience. Why shudder at the generosity of women, masters of stitches and ribbon and string? Making, and giving and giving back. Sending recipes back and forth, each time with a slight revision.

Friendship may, in the end, be the surest form of curation. I will go home and scribble and sort, arrange and rearrange, and tidy up and think; in a week or so a letter may come. And I will know there is someone sitting at her kitchen table just as I sit at mine, underlining for me what matters.

Collage Life, ©Iskra Johnson

b.sue says

Abridged. Like!

Iskra says

Thankyou B.Sue!

Jere Smith says

So beautifully written, Iskra. We live in a collaged world.

Jere

Iskra says

Thank you Jere. I thought of your cabinet of curios and your wide ranging mind as I wrote this. #likeminds!

patty haller says

Thank you for this beautiful writing, Iskra!

Karen Johnson says

Such a thoughtful piece. I long to see it laid out in a little square book with lots of white space, so I can absorb it one or two paragraphs at a time.

Kappy Trigg says

Iskra this is amazing. The words and images so well placed. Thank you for sharing this.

Kappy

Deb Craig says

thnx for nice / compelling / relaxing visuals with subtle coloration. Very nice.

Much as i like to read, for some reason i canNOT concentrate when reading onscreen.

Found this thru FB group Collage Artists Worldwide.

Amanda Michele says

Ah, this is at once tender and robust – a beautiful ode to these times. Thank you so much for sharing your moments and reveries. You’ve inspired me to buy more stamps.

Christine Olson Gedye says

Much to delight in here, a collage in its own right. Thank you for all your curated and deftly assembled thoughts. C.