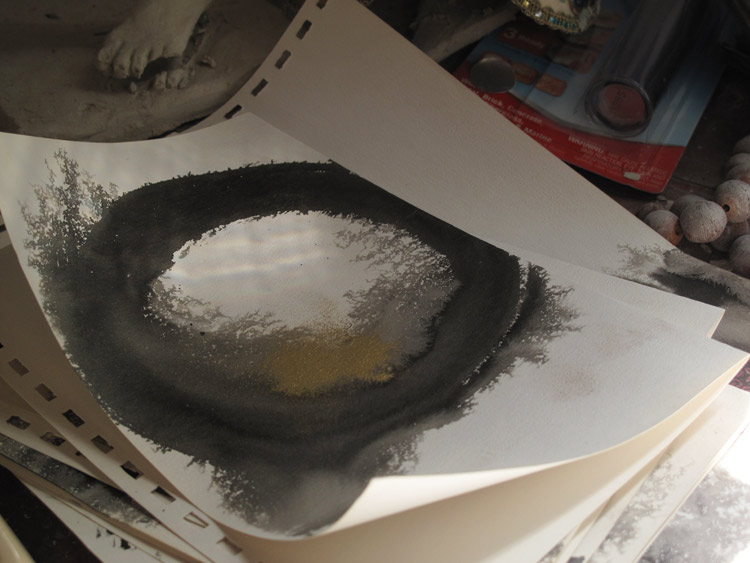

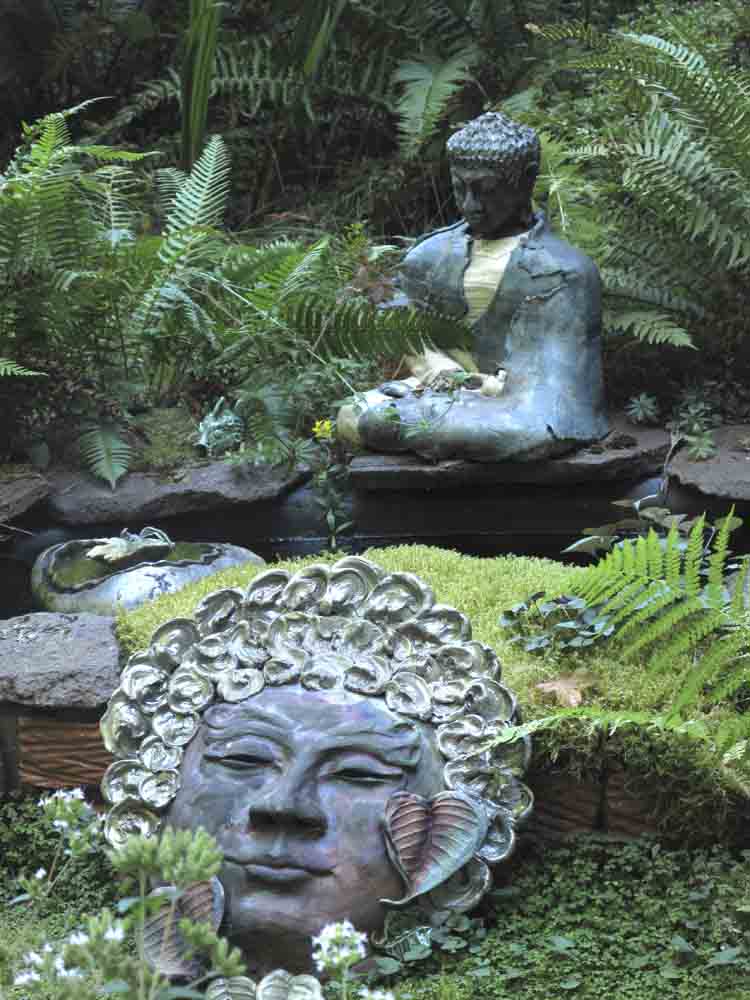

I visited the raku studio of artist and zen teacher Anita Feng in late August at the height of Indian summer. The trees had not yet caught fire, but the air held an expectant shimmer. Within a few weeks the leaves would deepen and turn, and that abalone glaze particular to this latitude would paint the city in subtle iridescence. If there is a season for raku, it is Autumn. This ceramic art form relies upon the drastic extremes of water and fire. It epitomizes the dynamic of change and working skillfully with change, and in this way it is the perfect parable for Zen practice.

I had met Anita earlier in the year, after seeing her Buddha sculptures in various galleries and visiting the Blue Heron Zen Center, where I very much enjoyed her clear-eyed Dharma talks. I was intrigued by her complex background as a poet, a potter and a 30- year practitioner of Zen in the Korean tradition. As a poet she has won many prestigious awards, including an NEA grant and the Pablo Neruda Prize and published two books of poetry. Much of her pottery background has been devoted to the making of ocarinas, the diminutive bird-shaped flutes of ancient times. I was very curious to know how she wove the threads of these different paths into her current focus as “The Buddha Maker.” As well, how she reconciles the traditions of devotional practice with a modern audience. I caught up with Anita as she took a break from preparations for Art in the Garden, an annual art and sculpture event held at Bellevue Botanical Gardens. We talked for many hours, and this interview is a combination of notes, memory, and email.

IJ) The power of Buddha images traditionally lies in their impersonality. The faces are based on years and years of archetypes, repeated and refined over centuries. In devotional statues the emotional element of mirroring, of liking what looks like us, is complicated by the idea of holiness or aspiration. In fact, we don’t really want the Buddha to be just like us. In contrast to the requirements for presidential candidates, we don’t judge the Buddha’s success by whether he would be a great guy to have a beer with. That not-having-a-beer-with characteristic is part of the deal. The statue is clearly not us. It is an idealized extreme. If we are from Northern European stock or African or Hispanic the Asian/Indian character of the features is not ours. This can be alienating. Alternatively we can experience it as restful–the burden of being personal is lifted, and we can surrender to something outside of ourselves.

One of the most difficult things to do in sculpture is to create a face that is universal, that does not create a subjective reactive “I don’t/do like you” response in the viewer. When a human being sees a face, whether on a real person or in a work of art, an immediate relationship arises. What guides you as you create the faces of your sculptures, and does your process or state of mind change as you work on the body?

AF) There is a way in which iconography, indeed in which history, prettifies or re-invents the past to teach and/or inspire (or divert!) the following generations. As Zen students, as students of our own particular moment world, we have the responsibility to sort out inventions and embellishments from the root teacher/teaching.

For me, in sculpting a face, I am looking for a meeting place of the particular with the universal. There is, in all iconography, an ideal that is presented. (ie.- calm, equanimity, peace, centeredness). But from the teachings and enlightened experiential wisdom that has been passed down over the generations, the only way these qualities can arise and be authentic is in the present world/moment experience. So I create faces that reflect our/my world, but it should be said, this is a world that contains all the references of the past as well. We are, as creative creatures, a composite of past, present and future, all together.

In the physical act of working the clay I reflect these two essential components (moment world, infinite time and space) in this way: the fleeting, sometimes ragged and torn movement suggested in the body/robes…. paired with the enduring, infinite stillness within the calm face. These faces may be sad, happy, or in between — but all mean to suggest a still equanimity. There is something wonderful and necessary about having an idealized image that inspires us to think that equanimity is possible. What is dangerous is when we start to believe “equanimity looks like this.”

IJ) Where and how do you draw your line between tradition and innovation? I have noticed that you have discarded many of the familiar aspects such as the stylized hair and dome-like stupa on the top. The robes can be completely wild.

AF) I don’t know if I draw any real lines between tradition and innovation. I do feel it’s important to reach back and honor aspects of the tradition where it seems to fit and serve. If the figure becomes too abstracted from the archetype people don’t have an anchor. I have chosen to keep the stylized ears, because it is an easily recognizable feature of a Buddha, but also because it points to a very real person, a privileged wealthy youth who became Buddha –with his ears elongated from the weight of heavy earrings.

IJ) How does your poetry background influence your ceramic work?

AF) I’m sure it’s a huge influence as poetry has served as my life-long play with invention and intuition. So this life of work/play that makes use of everything at hand helped me to apply it to this other medium of clay.

IJ) Does your relationship with words as a poet affect your Zen practice, or does it affect how you integrate it into your life?

AF) Absolutely, yes, my relationship with words, my study of language and meaning is directly related to Zen practice on two main levels.

A. Meaning. Both Zen and poetry call for a keen responsibility for meaning. There’s an old Zen saying, “Zen eyes are never reckless.) So while spontaneity is key, spot-on, hitting-the-bull’s eye meaning is essential. By “meaning” I mean hitting, with language, the root and not getting lost in descriptive branches.

B. Keeping to what is alive. Both Zen and poetry make a practice of vitality. William Carlos Williams, the great American poet, is famous for his saying, “Not in ideas, but in things.” Same in Zen. The idea or descriptor is never IT; best to evoke the thing, experience itself!

IJ) In chanting in particular, words are a big part of Zen practice. Poetry/chant/your words/not your words/English/Sanskrit — how does this work for a person who lives in the modern world of literature?

AF) I was first drawn to poetry for its music (and I am, still). Meaning comes second. So unlike many others, I suppose, I am not so concerned about the words in the chants. I take it as a practice of just chanting, just singing, just feeling the heart as it opens and gives voice. At risk of opening up another topic, I would suggest that the “idea” of “personal creativity” is something of a misnomer. Creativity is, yes, the person, but as he/she intersects with all the other variables of present moment experience. Meeting at the cross-hairs of lived experience, the voice that emerges from the individual is the potential for creative force. In both of my mediums I rarely start with a topic or idea. I start with music — in poetry this would be the particular music of a word or phrase as it appears in my mind. In clay, it would be the physical music of clay, if that makes any sense.

IJ) You spent many years making ocarinas, a much-beloved folk instrument that probably many people have never heard of. How did this practice affect what you do now?

AF) Having made ocarinas, tuning them up over the course of thirty years, give or take, I’ve learned how to listen. And I’ve learned that there is no end to it, to listening closer, and closer. So, the direct application to what I’m doing now is being able to apply a skill of listening to several things, all the present moment factors of the creative process — the clay, the clay’s condition, my mood, my fingertips, the sculpting tools, even the sound of their progress across the surface of the clay. And a big one, time. Listening, allowing for the hand of time to contribute its part. Patience! Space!

We’ve come back again to music. The spaces between sound and the relationship between the two. The same as for poetry. There is an old Chinese saying about pottery that goes something like: you can’t understand a pot by its form, it’s only when you cut it open and see the space inside that you can understand it –and the space within is essential to its usefulness and beauty.

Thank you Anita for sharing your work space and thoughts on your creative path. Below, images from Anita’s studio and a selection of works from Golden Wind Raku, available at her etsy shop. In-studio and garden photos © Iskra Johnson, others © Anita Feng. At the end of the post you will find some links to more information about raku, Buddhist practice and iconography.

“I am interested in showing the flow of engagement, which may reflect vulnerability and fear, yet finds stillness within that. The only way the absolute can come through is through the subjective.” —Anita Feng

Additional Resources:

Anita’s poetry books are: Internal Strategies and Sadie and Mendel

An interesting piece about the difference between Japanese and American raku: http://www.paulsoldner.com/essays/American_Raku.html

How to draw a perfect Buddha: http://buddhist-temple.com/drawing-lessons.html

A panoramic curriculum of contemplative art: http://www.shambhala.org/arts.php

One of Anita’s references for research on the Buddha: “The Life of Buddha As Legend and History” by Edward J. Thomas

lana sundberg says

Gorgeous work.

Thank you for sharing the beauty and wisdom of Anita’s work.

Michele Lisenbury Christensen says

I love the way your questions, Anita’s work and her voice, and your photos all dance together in this interview. And the sense of season and place: crystalline. Thank you!

jill i says

Wow, what a beautifully written and thoughtful interview. Thanks Iskra! And Anita. 🙂

Meg A. says

This is a lovely work of art in itself, Iskra! What a rich discussion—so many ideas to contemplate. Thanks for creating it and sharing it. I know a few artists I’d like to pass it along to.

Deep bows!

James says

Thanks Iskra for this wonderful interview, and Anita for your beautiful work.

del webber says

I’m particularly fond of two thoughts shared( paraphrased)-

It’s not so much the description to be appreciated, but the ‘thing’ itself.

One finds understanding of a vessel not by its form, but by cutting it open and finding the beauty and usefulness within.

I’m going to let those marinate for a long time. thank you